This is my lecture to a conference at Westergasfabriek, in Amsterdam, called Creativity and the City, on 25 September 2003.

In Rajhastan, travelling storytellers go from village to village, unannounced, and simply start a performance when they arrive. Although each story has a familiar plot – the story telling tradition dates back thousands of years – each event is unique. Prompted by the storytellers, who hold up pictorial symbols on sticks, the villagers interact with the story. They joke, interject, and sometimes argue with the storyteller. They are part of the performance.

Hearing about these storytellers reminded how much we have lost, in the ‘developed’ world, of the un-mediated, impromptu interactions that once made cities vital. We now design messages, not interactions. The world is awash in print, and ads, and billboards, and packaging, and spam. Semiotic pollution. Brand intrusion at every turn.

Our buildings are now about one-way-communication, too. Sports stadia, museums, theatres, science and convention centres. Such buildings do an accomplished technical job: they deliver pre-cooked experiences to passive crowds.

And whom do we have to thank for this semiotic pollution, for the catatonic spaces that despoil our physical and perceptual landscapes? The “creative class”. That’s who’s responsible. In the same way that mill owners optimised mass production, the creative class has optimised the society of the spectacle.

At least mill owners bequeathed us well-made industrial cities. The creative class will be less fondly remembered. Their legacy is meaningless, narcissistic cities.

Luckily, the era of the creative class is over. Point-to-mass advertising, onanistic art, and big-ticket spectacles, are over. We are in a transition to a post-spectacular, post-massified culture. Our cities, from now on, will be judged by their capacity to foster collaboration, encounter, intimacy, and work. Much like cities used to be judged, before they fell into the hands of the creative class.

I’ll explain more about these design criteria for cities in the second half of my talk. In the first half, I explain just why it would be foolish to dedicate our cities to ‘creatives’ and the impoverished, sender-receiver model that informs their activities.

Spectacles make us blind

There are three reasons why it would be foolish to entrust the future of our cities to the creative class.

The first is its autism. Autism is defined in Webster as “absorption in self-centred subjective mental activity, especially when accompanied by a marked withdrawal from reality”. An example. A week ago I attended a meeting here in Amsterdam on the subject of “Hosting” The invitation posed an interesting question: “What is the relationship between art biennales, and their host cities?” Many international art powerbrokers turned up for this meeting, which was hosted by an organisation called Manifesta. Ten or 12 of them sat round a table.

In the event, the meeting was a waste of time and space. All the curators and critics and producers discussed were ‘viewers’ and ‘audiences’ and ‘publics’. They banged on endlessly about the business of biennales, but lacked any insight into the changing nature of business. It dawned on me, as I struggled to stay awake, that Art has become most attractive to the interests it once ridiculed.

The tourism industry loves art because its events and museums are ‘attractions’. Property developers love art because a bijou gallery lends allure to egregious projects. For city marketers, an art biennale bestows glamour, and an aura of intelligence, on a city.

“Our events are not summer camps”, pleaded Franco Bonami, director of the Venice Biennale. (Mr Bonami invited more than 500 artists to this year’s event). But he did not mention one single word about what, if anything, these 500 people had to say – or why the rest of us should care.

After two hours I had to leave. “Hosting” felt like a sales meeting for Saga Holidays.

So then I went to Japan where Prada, which is said to be 1.5 billion euros in debt, has lavished $87 million on a new Herzog and de Meuron-designed store, in Tokyo. Now for Aaron Betsky, the Prada building would be a right and proper thing to do. Shopping, he just told us, is the fundamental purpose of cities today.

For me, the whole Prada project smells like the last days of Rome. The Plexiglas exterior, which is like bubble-wrap, certainly stands out. The new shop is on the Tokyo equivalent of P C Hooftstraat. (Amsterdam’s fashion street).

I popped in for a look.Ten minutes. Quite nice. Been there, done that. Prada spent 87 million bucks on a clothes shop that contained nothing I wanted to buy, but that’s their right. A creative consultant called Christopher Everard told The Economist that, “by using iconic architects, the label is building brand equity”. Mr Everard’s firm is called “InterLife Consultancy”. I emailed him the suggestion that he change its name to “Get A Life Consultancy” – but he has not replied.

Besides, Prada’s investment is chickenfeed, a mere grain of corn, compared to Tokyo’s Roppongi Hills tower. This 800,000 square metre monster had just opened when I was there. No expense has been spared by Yoshiko Mori, its developer, to compensate local people for the sacrifice of their old neighbourhood to progress and creativity. Several traditional features have been retained, I was told, including a Japanese garden, a Buddhist temple, and a children’s park.

When I visited Roppongi Hills, these human-scale traces of old Tokyo proved hard to find. They were hidden among the 200 shops, 75 restaurants, and a zillion square feet of office space and apartments that fill the building.

The Zen garden may be lost, but compensation and enlightenment await you at the top of the tower: the Mori Museum of Art. A Who’s Who of the global art establishment – including Nicholas Serota from the Tate, and David Elliot, its British Director – have joined this lavishly funded enterprise. Glenn Lowry from the New York MoMA is also on board, apparently unperturbed by his client’s appropriation of the Moma name.

The museum opens next month with a biting and critical look at the modern society which begat it. The show is called, â€Happiness: a survival guide for art and life”.

Only people with a ‘community passport’ are admitted to this Xanadu of art-as-happiness. The passport, curiously, closely resembles a credit card. But still: it gains you access to all those shops and restaurants and – piece de resistance – an orange bar designed by Conran Associates.

The art museum itself was not yet open when I visited, but six museum shops were. They were doing a roaring trade.

“Art, design and happiness” says the brochure, “the kind of place that we want to become”.

Not of all of us, Mori-san. “Tourism – human circulation considered as consumption – is fundamentally nothing more than the leisure of going to see what has become banal”. Guy Debord wrote that more than 40 years ago, in The Society Of the Spectacle. He would not have warmed to Roppongi Hills.

In much the same way that that tourism kills the toured, ‘cultural industries’ like museums-and-shopping destroy diversity and desolate their host environment. CIs are like GM crops: bland, tasteless, and a threat to the ecosystem.

I do not deny that the economic case for the creative class is strong. After all, designing all those spectacles is big business.

A new trade fair and exhibition in Philadelphia, which calls itself “Exp”, announces itself as “The Event That Defines The Experience Industry”. I didn’t go to Exp, but I did go to the website. The middle-aged, white male speakers boasted a remarkable collection of jowls and bad haircuts. They promised to tell me, “how to gain a greater share of your guest’s discretionary time and disposable income”; how to “destroy the myth that great experience need huge budgets” (sic); and, “how to surf the generational shift”.

The website did not mention a session on how to speak English, but this omission did not deter the creative classes. They flocked to Exp – enthralled. no doubt, by its convenient clustering of four key themes: Corporate Visitor Centres, Retail, Casinos, and Museums.

The other big spectacle business is sport. Sophisticated Paris, in its bid for the Olympics, says that sport is replacing culture as an attractor in urban regeneration. “The role that investment plays in the Games of the 21st century will be comparable to that played by industrialisation at the end of the 19th century”, burbles their bid.

Claude Bebear, chairman of the Paris Olympic Committee, does not think of sport as kicking a ball around a field. He thinks about twenty million dollar sponsorships, and the well-being of the people who provide the spectacle. Claude’s plan for a sporty Paris features private road lanes for the exclusive use of athletes and officials. A travel time of 12 minutes, from bed to track, is promised to the muscle-bound sportspersons and their crypto-fascist paymasters. If the bed-t-track journey proves too taxing, an internet and electronic games centre will be provided to “help athletes relax and get in touch with the outside world”. Le Moniteur, eds, 2001, Paris olympiques: twelve architectute and urban planning projects for the 2008 games, Paris, Editions du Moniteur

Action Man

But I digress. I’ve made the point that pre-programmed cultural ‘attractions’ and ‘experiences’ are on the wane. The nightmare of “art and design as happiness” is nearly over.

And I should also stress that the “creatives” who make them are not personally to blame. They – we – are the symptom, not the cause, of a cultural affliction that touches us all.

So what are alternatives? This brings me to the second part of my talk.

Tor Norretranders, in his book The user illusion, explains beautifully what’s missing from the mediated, specacular, dis-located, and disembodied experiences that blight our lives. Once we know what’s missing, we can put it back.

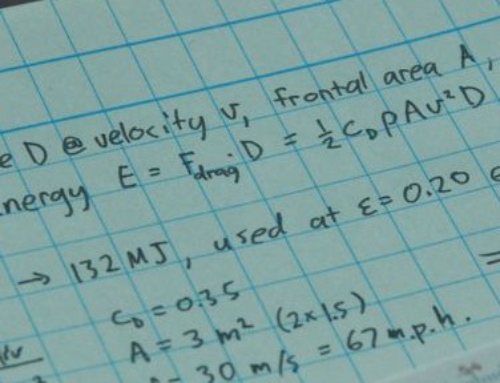

“Most of what we experience we can never tell each other about” writes Tor. “During any given second, we consciously process only sixteen of the eleven million bits of information that our senses pass on to our brains”. In other words, the unconscious part of us receives much less information than the conscious part of us. We experience millions of bits a second but can tell each other about only a few dozen.

Humans, concludes Norretranders, are designed for a much richer existence than processing a dribble of data from computer screen, or a wide-screen display in Times Square.

There is far too little information in the Information Age. Spectacles may be spectacular, but they are low bandwidth.

“I believe that a desirable future depends on our deliberately choosing a life of action, over a life of consumption. Rather than maintaining a lifestyle which only allows to produce and consume, the future depends upon our choice of institutions which support a life of action”.

That was Ivan Illich, in 1973. Thirty years ahead of the rest of us, Illich argued for the creation of convivial and productive situations – including our cities. A sustainable city, Illich understood, has to be a working city, a city of encounter and interaction – not a city for the passive participation in entertainment. www.infed.org/thinkers/et-illic.htm

What matters most in a post-spectacular city is activity, not architecture. As the director Peter Brook has said, “It is not a question of good building, and bad. A beautiful place may never bring about an explosion of life, while a haphazard hall may be a tremendous meeting place. This is the mystery of the theatre, but in the understanding of this mystery lies the one science. It is not a matter of saying analytically, what are the requirements, how best they could be organized — this will usually bring into existence a tame, conventional, often cold hall. The science of theatre building must come from studying what it is that brings about the more vivid relationships between people.”

Tame, conventional, cold. How many buildings do those words recall? Torsten Hagerstrand has studied dysfunctional spaces – and good ones – and how people use space and time for thirty years. He says it is the ability to make contact with people that determines the success of a transport system or location. Hagerstand [q in Whitelegg) Hagerstrand T, Space time and the human condition, in Karlquist A, Lundquist L, and Snickars F (eds) Dynamic allocation of urban space, Saxon House, Lexington MA 1975

Peter Brook, too, as I said, asked us to focus on what it is that what it is that brings about “the more vivid relationships between people.”

One of those things is the mobile phone. It’s impacting remarkably on our interactions with space and community. Mobile phones stimulate connections between people who already know each other, or have something in common. They can also help crowds assemble, as we saw in Seattle, in 1999.

That’s not major news. The more interesting change is the way wireless communications connect people, resources, and places to each other on a real-time basis, and in new combinations. Demand responsive services, as they call them in the (service design) trade.

Traditional city planning designates different zones for different activities: industrial, residential and commercial. Telecommunications are changing the nature and inter-action of activities that “take place” in these three types of location. Think of the taxi systems you have encountered. They are demand responsive services, to a degree. The old model was that you would ring a dispatcher; the dispatcher offers your trip all the drivers on a radio circuit;One driver would accept the job; and the dispatcher would send that taxi to you.

A better way, now being introduced in many cities, is that you ring the system; the system recognises who you are, and where you are; it identifies where the nearest available taxi is; and it sends that taxi to you. Dynamic, real-time, resource allocation.Now: replace the world “taxi” with the word sandwich. Or with the words, “someone to show me round the back streets of the old town”. Or the words, “a nerd to come and fix my laptop” Or the words, “someone to play ping pong with”. Or suppose you feel like helping out in a school, and hanging out with kids for a day.

In every case, networked communications, and dynamic resource allocation, have the potential to connect you, with what you want. It just needs to be organised.

You could be a supplier, too. Perhaps you have time on your hands. Make good sandwiches. Know the old town like the back of your hand. Have a nerdy daughter who’s looking for work. Know there’s a ping-pong table in Mrs Graham’s garage, which they never use. Or perhaps you don’t feel like dealing with Form 5 on your own this week.

What do you do? You call the system. Or the system calls you.

The reason I’ve jumped from the creative class, to mobile phones and networks, is this. If the post-spectacular city is about person-to-person encounter, technology can help us achieve that. The consequence can be a profound change in the ways that we operate, and live, in cities.

With networked communications we will be able to access and use everything from a car, to a portable drill, only when we need it. We won’t have to own them, just know how and where to find them.

Did you know that the average power drill is used for ten minutes in its entire life? Or that most cars stand idle 90 per cent of the time? The same principle – of use, not own – can apply to the buildings, roads, squares and spaces that fill our cities.

But the killer app is access to other people. People is what makes cities different from other places. The creative city will be the city that finds ways to strip out all the transaction and infrastructure costs that make it expensive to hire people to help us do stuff.

In retrospect, we got the information age completely wrong. We thought it would be smart to remove people from services: we called it ‘disintermediation’. It reads as it was: a pain in the neck.

We also thought we could do without place.Nicholas Negroponte stated in Being Digital, the dotcommer’s bible, that “the post-information age will remove the limitations of geography. Digital living will depend less and less on being in a specific place,at a specific time”. Lars Lerup,dean of the architecture school at Rice University – and a dotcommer manque – proclaimed in a book approriately named Pandemonium that “bandwidth has replaced the boulevard. Five blocks west has given way to the mouseclick. After thousands of years of bricks held together by mortar, the new metropolis is toggled together by attention spans.” Brandon Hookway, 1999, PANDEMONIUM Princeton Architectural Press New York.

All that stuff was, in retrospect, piffle. But we all did it, including this speaker. He apologises, and pleads only that he is a tiny bit wiser after the event.

The point is that the information age has been added to the industrial age. Telematic space has been added to Cartesian space. The one did not supplant the other.

And mobile phones and networks do not make the city disappear. On the contrary, they render the city itself more powerful as an interface.

Sometimes this is at the level of tools. Experiments are under way in which mobile phone act like a remote control to activate technology in our surroundings. You stand at a bus stop, and summon up your personal web page on one of the panels. J C Decaux, or Viacom Outdoors, control millions of such urban surfaces which could be used for such an application.

Researchers at Interaction-Ivrea, in Italy, had another good idea: connect these displays to the printers in ATM machines. You could print out SMS messages, or a local map, on the ATM printer.

Other projects treat the whole city, not just its furniture, as an interface. A project called New York Wireless, for example, has identified more than 12,000 wireless access hot points throughout Manhattan alone, and put their location on a website.”The result is a new layer of infrastructure”, says co-founder Anthony Townsend.”But no streets were torn up. No laws were passed. This network has been made possible by the proliferation of ever more affordable wireless routers and networking devices. Mobile devices re-assert geography on the internet”.

Marko Ahtisaari, a future gazer at Nokia, says that enabling proximity – getting people together, in real space – has become a stratgic focus, the killer application of wirelsss communications.”Mobile telephony might seem very much to do with being apart, but a lot of telecommunications behaviour is aimed at getting together physically in the same place”, he says.

Proximity and locality are natural features of the economy. Worldwide, the vast majority of small and medium-sized companies – that’s most of all companies – operate within a radius of 50km. Most of the world’s GDP is highly localised. Local conditions, local trading patterns, local networks, local skills, and local culture, are critical success factors for the majority of organizations.

Mobile phone and wireless-enabled gadgets enable us to access people, or resources, or services – just-in-time, and just-in-place.

By doing that, they also design away the need for mobility, or much of it. Demand-responsive services, combined with location-awareness, combined with dynamic resource allocation, have the capacity dramatically to reduce the mobility-supporting hardware of a city: its roads, vehicles, malls and car parks.

Imagine there’s a kind of slider on your phone. You set it to “sandwich” and “within five minutes walk” or “within a five dollar cab ride” – and use those parameters to search for whatever it is you need.

You dont need to own it. You don’t even need to go far to get it. You just need to know how to access it.

So what to do?

Talks like this one are supposed end with a list of things you might do on Monday morning. But I just criticised creatives for over-designing our cities, so it would be hypocritical of me to give you a list of things to do.

So let me summarise. I have said that we are in a transition to a post-spectacular, post-massified culture. It’s for this reason that it would be foolish to hand over our cities to the “creative class”. They just don’t get it. More to the point, their business model drives them on. Our cities are over-designed because the creative classes get paid for designing things.’Creatives’ don’t get paid for leaving well alone.That’s a conundrum we’ll need to resolve.

The second part of my talk touched on some of the ways wireless communication, and networks, enable people, places, and things, to be connected in new and often unexpected ways – and times. I also explained that the information age has not replaced the real-word age – but it is certainly transforming the ways we use and live in it.

I do have one suggestion for what you can do on Monday morning. Go out and buy Italo Calvino’s wonderful book, Invisible Cities – of which the following is an extract:

“The Great Kahn contemplates an empire covered with cities that weigh upon the earth and upon mankind, crammed with wealth and traffic, overladen with ornaments and offices, complicated with mechanisms and hierachies, swollen, tense, ponderous. “The empire is being crushed by its own weight†Kublai thinks, and in his dreams,cities as light as kites appear, pierced like laces, cities transparent as mosquito netting, cities like leaves’ veins, cities lined like a hand’s palm, filigree cities to be seen through their opaque and fictitious thickness”