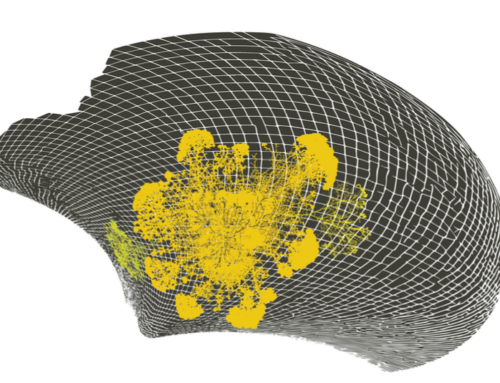

(Pic: Being Nicely Messy, CRIT, Mumbai) In London, I did this interview with Midtown Big Ideas Exchange:

Q Do you believe cities are rational or organized and, if so, what makes them this way?

A Cities are often conceived in a rational way but usually take on a non-rational life of their own – and thank goodness for that. The spatial grid of New York, for example, co-exists with a bewildering array of unofficial activities at street level. The same goes for Mumbai; her city map looks clear enough – but it does not equip the visitor to understand the apparent chaos of daily life on the ground. The best cities combine both: Orderly features – such as trains that don’t crash – and enough disorder so that rich transactions between diverse people can thrive.

Q Are cities really the place to ‘get rich quick?’ Do they ultimately make us into happier, healthier and more prosperous individuals? What are the key principles that make a good city and a city good for us?

A People have been coming to cities to make their fortune for centuries, and that’s not about to change. The trouble starts when business and money-making dominate all other concerns. When that happens, cities stop being sites of social innovation. Although London is in danger of suffering that fate, there are still examples to celebrate of local projects whose vitality is based more on social quality than capital accumulation. Craft brewers, and bread projects like E5 Bakehouse, are great examples. http://e5bakehouse.com

A What has your travelling experience taught you about making cities more sustainable in the years to come?

Q What makes cities resilient are people. Systems, especially technical ones, come a distant second. I was impressed in Chile, for example, that after an earthquake – and they have a lot in that country – 80 per cent of rescues are carried out by civilians. You saw that same pattern in England during the floods; citizens helping each other. But resilience is not just about responding to emergencies. My favourite example is healthcare. Ninety-five per cent of person-to-person care happens outside the world of hospitals, doctors, and costly drug treatments. People-powered health and care are at the heart of an economy in which life is valued more than money.

Q How does tech influence city life – is it the key to urban innovation? Will it damage or regenerate urban beauty?

A Cities have been suffused by technology for centuries – roads and bridges; sewers; train and telephone lines. The internet and mobile phones are just the latest layer of tech to be added. For me, the test of whether a technology is significant for cities is whether it fosters social transactions and encounters. Based on that filter, mobile phones are transformational, but the Internet of Things is not. Uber and AirBNB have disrupted legacy taxi and hotel industries – but much bigger changes are on the way with platforms like LaZooz that enable distributed mobility platforms to be owned by the people who use them.

Q Will London’s urban future be something to look forward to? Or will cities become increasingly cramped by rapid urbanisation?

A What a healthy city needs, and what the Real Estate Industrial Complex needs, are two different things. The world is over-built. New buildings, and politicians posturing in hard hats, are old paradigm indicators of economic health. The health of the soils, fresh air, and biodiversity, are better measures of progress than builders’ cranes. The best cities today give priority to life corridors and ecological infrastructure: horizontal surfaces being planted, vegetative buffers, open spaces, roofs, gardens and public parks used for rain water retention, rivers and creeks being restored to health. The very concept of urban development is being replaced by a whole system, whole landscape approach at the scale of the Bioregion.

Q What would your strategy be for ensuring cities remain environments where entrepreneurs and business alike can thrive?

A: My strategy is to put the vitality of social end ecological systems at the top of the agenda, and to encourage business to focus its creativity on those objectives. In planning terms, this translates into support for sites of social creativity: maker spaces, recycling projects, craft breweries, bakehouses, productive gardens, community kitchens, and the like. Every city needs a lot of these and other commons based spaces. In terms of business support, as such, we need to focus on platform co-ops in which value is shared fairly with the people who make them valuable. “Value” here means shelter, transportation, food, mobility, water, elder care – the lot.

Q How can we make ‘smart cities’ a reality of the future? How can we integrate environmental thinking with plans for change?

A The smart cities crowd treats the places we live like a giant train set that needs to be attached to huge servers run by them. A better approach is to focus on social smarts, with technical ones as support. A good place to start is with two questions: “Where will our next lunch come from?” and, “How can we make that place healthier?” When cities concentrate on the health of places that keep them fed and watered, opportunities for innovation emerge: new ways to share resources, and collaborate; new kinds of enterprise such as food co-ops, collective kitchens, community dining, edible gardens, new distribution platforms.

Q Would you describe your new book ‘How to Thrive in the next Economy’ a handbook for those seeking opportunities in developing cities of today?

In 35 years as a guest in what used to be called the ‘developing’ world, I’ve come to a startling conclusion: People who are poor in material terms are highly accomplished at the creation of value in ways that do not destroy natural and human assets as too much of our economic progress does. My book celebrates an amazing care economy – care for each other, for the land, for water, for biodiversity – that already exists – but can always be improved. The future of cities is to embody a new story about what the economy is for – a leave things better one. This is the one kind of growth that makes sense, and that we can afford: the regeneration of life on earth, including in cities.