An introduction to flow issues for the October 2002 issue of Archis, the main media partner of Doors for its conference.

What happens to public space when there are hundreds of microchips for every man, woman and child on the planet – and when most of these chips talk to each other? What are the implications for buildings in a world suffused not just with sensors, but also with responsive ‘smart’ materials, and actuators?

Right now, the military are providing most of the answers to those questions. They are driving developments in the use of sensors, tags and remote monitoring in the physical world. Military-funded researchers are developing an operating system for smart dust’s self-organizing sensors and effectors; these tiny devices, that can manipulate matter, will be able to form wireless networks without human intervention. John Gage of Sun Microsystems anticipates that we will soon sprinkle “smart dust” over battlefields – clouds of tiny wireless sensors, thermometers, miniature microphones, electronic noses, location detectors that will provide information about the physical world, and the people crossing it, to battlefield commanders.

Meanwhile, in business, companies are wiring up digital nervous systems that connect together everything involved in their operations: IT systems, factories and employees, as well as suppliers, customers, and products. The aim is to be able to monitor everything important in real-time. Companies are developing ‘dashboards’ that will measure key indicators and compare their performance against goals – and alert managers if a deviation becomes large enough to warrant action. Control-obsessed firms – among them GE, the world’s largest – aspire to convert their information flows into a vast spreadsheet. They aspire to create, as Ludwig Siegele put it in The Economist, not a new economy but a “now economy”.

This new wave of technology confronts us with a design dilemma. We are filling our world with complex technical systems – on top of the natural systems that were already here, and social/cultural ones that evolved over thousands of years – without thinking much, if at all, about the consequences. During the 1990s, we were told that complexity was ‘out of control’ – too complex to understand, let alone to shape, or re-direct. But ‘out-of-control’ is an ideology, not a fact.

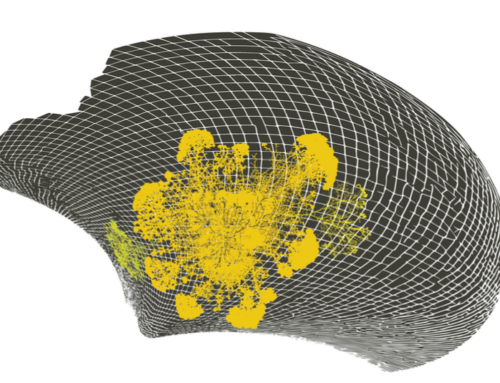

Flows can be designed. The design agenda for flow has two parts: designing ways to perceive flows, and re-designing the design process itself. Firstly, in order to do things differently, we need to see things differently. We need dashboards for cities and buildings. We need to experience the systems and processes on which we depend, in order to look after them. We know, for example, that buildings consume a lot of energy – but we don’t ‘see’ heat flying out of the windows. If we did, our behaviour would probably change. Designing experiences won’t be easy: systems are, by their nature, invisible, and we often lack metaphors or mental models to make sense of the bigger picture. But many affective representations of complex phenomena have been developed in recent times: physicists have illustrated quarks; biologists have mapped the genome; doctors have described immune systems in the body; network designers have mapped communication flows in buildings. And as Malcolm McCullough points out in this edition, geodata industries are exploding.

The purpose of systems literacy in design is not to watch from outside – it is to enable action. The second challenge for design in the space of flows, therefore, is the transition from designing things, to designing systems – and from a project-based to a continuous model of the design process. Systems and processes never stop changing, so neither can design. As we move from a project model, to a continuous model of design – which is increasingly the norm in information technology, and in management consulting – we need new metaphors for what we do: games, simulations and play may be more appropriate modes of designing flows.