The Aral Sea in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic of Uzbekistan, is a supremely testing context.

It was once the world’s fourth-largest inland lake but, starting 100 years ago, large-scale irrigation triggered the sea’s retreat. By 2000, more than 90 per cent of its surface area had disappeared. The result: multi-system crises that affect people, ecosystems and the economy in myriad ways.

Can design resolve the situation??

On its own? Of course not. No magical bullet solutions – technological, or design – will revers esocial and ecological damage that’s unfolded over the best part of 100 years.

But there are always next steps to be taken – and this is where the new Aral School comes in. Its purpose is to increase the health of social, ecological and economic systems.

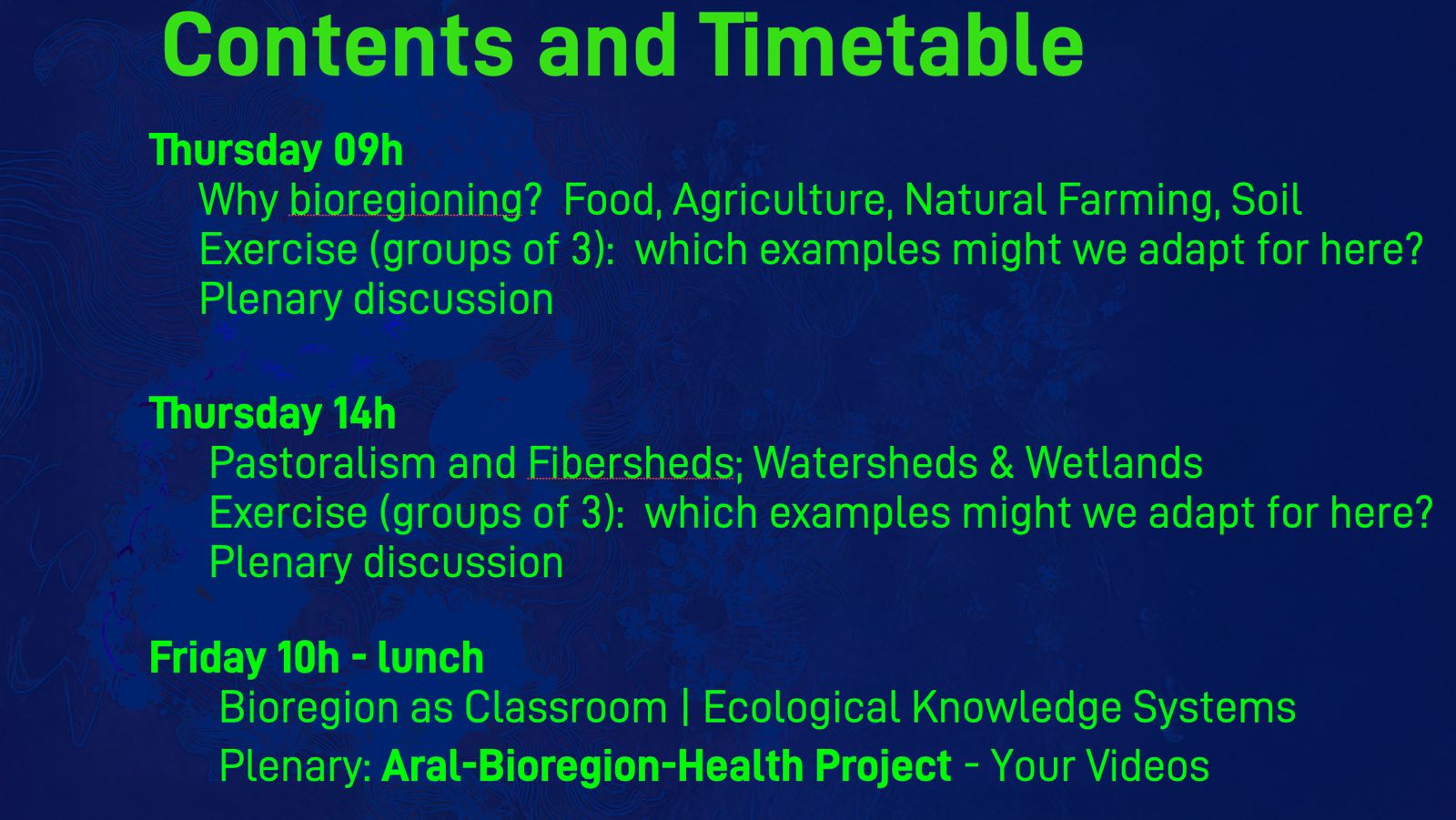

My contribution, as an invited lecturer, was to suggest that the school design its interventions as a form of health care – using the idea of bioregioning as a lens.

(The following text is a personal reflection on my recent visit. It does not represent the views of Aral School and its leadership).

Commissioned by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, and led by Jan Boelen, it will research, design and test system interventions into this highly complex social-ecological context.

The Aral School’s interventions will not be parachuted into the region from on high. On the contrary: Thirty seven million citizens live with the consequences ecological devastation every day – and have done for generations – so the School has set out to complement their lived experience.

Its work will also complement an already extensive restoration ecosystem. Several landscape-scale restoration efforts are under way to revitalise ecosystem biodiversity. Local scientists are involved in an Aral Sea Wetlands Project. 500,000 hectares of the former sea- bed are being afforested by 10 species of desert plants: saxaul, tamarisk, capsicum and others. Crop diversification is encouraged, with the planting of winter peas, mung beans, sesame. Micro-nurseries have been created that involve communities in restoring nature. Agroforestry is taking root. And incentives are in place to attract green investment in renewable energy, and eco-tourism.

At a microbial scale, too, agricultural innovations are being tested with local farmers.

Adding to this mixture, the Aral School brings together a multi-disciplinary team. Along with designers and architects, its 22-strong cohort of researchers – half of them international – includes data scientists, public officials, geophysicists, biologists, a phytoremediation expert, a linguist, an anthropologist, and an environmental historian.

These direct participants in the School are supported by mentors who are leading diverse restoration projects in the region already: water and food system experts, a microbiologist, a paleolimnologist, an archaeologist, a geographer.

In Nukus itself, Aral School is based near the Savitsky Museum. As a world class treasure trove of textiles, jewellery, ornaments, and dissident art, it’s a cultural anchor institution to die for.

So what, in such a context, can Aral School usefully add?

That discussion is now underway. (The school opened in January). My contribution, as an invited lecturer, was to suggest that the school should design its interventions as a form of health care using the idea of bioregioning as a lens.

One Place, One Health

A new awareness is sweeping the world: Health and well-being are properties of the social and ecological contexts in which people live – so we need to shift our focus upstream.

Modern biomedical health systems feature prominently in the GDPs of rich countries. But these treat the effects – but not the causes – of ill health. Even as the costs of modern biomedical health systems escalate, the health of living systems – air, water, soil – continue to be impacted adversely by human activities.

So what to do?

My first proposal in Nukus,was that we call the world’s small farmers, parents, and cooks – who give us good food – “health professionals” – and those running the modern biomedical system, “sickness professionals..

This ecological health perspective- a whole of system approach – involves what Didi Pershouse calls “a living, ongoing, relationship between, practitioner, patient, plants, and landscape”. It directs our attention to natural farming, ecological restoration, soil care, river and watershed recovery, community health.

Easily said – but how (if at all) does this care for place narrative connect with the lived daily experience of the region’s people?

I acknowledged, in Nukus, that few things are more irritating than Fly In Fly Out (FIFO) experts who tell local people what to do as soon as their feet touch the ground.

Nonetheless, I said, care for people, as well as for places, is already a massive, if unrecognised, feature of daily life around the world. Ninety five percent of care already takes place outside the bio-medical system – among carers, farmers, teachers, nurses.

Were things totally different in Karakalpakstan?

Rather than answer my own question, I went on to describe system interventions in other parts of the world, in contexts as challenging as those in Nukus. These examples are not models, or templates, to be applied as is – but could connections be made with developments happening there now?

Food, Ag, and Fiber

Before the ecological disaster, many parts of Uzbekistan were self-sufficient in food. But.starting in 1913, irrigation-based agriculture was extensively developed to grow water-intensive crops – primarily cotton, to supply the Soviet Union’s s textile industry.

As the area of irrigated land expanded more than threefold, the Aral Sea began to shrink. Its unique fishing ecosystem, that had supported local populations or generations, collapsed. Increasing volumes of dust and salt particles in the air reduced precipitation.and threatened the lives of more than 60 million people in Central Asia.

Today, although the Soviet Union collapsed 35 years ago, Uzbekistan’s economy continues to depend in substantial part on the export of commodity crops.

Is a post-irrigation economy out of reach?

My response to this question in Nukus was to say that transformational change had seemed impossible in other countries, too – until it wasn’t.

India, for example, has become a global centre of care-based agriculture right now – at least, if if the growth of Natural Farming movement is any guide.

In the Andra Pradesh Community Managed Natural Farming movement (#APCNF) more a million small scale farmers have pretty much taught themselves how to practice chemical-free farming with a focus on local and traditional knowledge.

The Natural Farming movement is now active in 20 of India’s 29 states, and the national government recently launched an all-of-government National Mission on Natural Farming (NMNF). The aim is to enrol ten million farmers into 15,000 natural farming clusters across the country.

Is this appropriate for Uzbekistan?

The lesson in India, and around the world, is that bioregional agriculture is not a single method. But whatever names we use – agroecology, natural farming, or regenerative agriculture – these practices are shaped by common principles and values.

These shared values crop up repeatedly in Uzbekistan’s policy, documents, too.

Agriculture is not not just about production and consumption of calories. It also creates ‘public goods’ in the form of social cohesion, public health, territorial development, food sovereignty, farmer livelihoods, learning, innovation, and biodiversity.

Small-scale farmers care for 80% of world’s biodiversity.

Farming is cultural work shaped by time, place, and care — it’s not merely about economic output. Building stronger local agroecological food systems can address intertwined crises of health, climate, biodiversity loss, and precarious rural livelihoods.

So what practical acts of care might Aral School develop with the farmers of Karakalpakstan?

I don’t know. That’s a conversation,going forward, forAral School .

But when I put that question last year to the APCNF in India, a five point to-do list emerged:

- farmer-to-farmer knowledge-sharing;

- shorter routes to market;

- on-farm diversification;

- village-scale diversification;

- appropriate agritech.

Potatosheds

That list is not a template for Uzbekistan, but a focus on food security is a priority for many countries – and not just poor ones. So I shared an experience Sweden that I thought might be relevant.

In a project called Back To The Land 2.0 a design school, Konstfack, posed the following question to a group of masters students: “what will a self-sufficient Hallefors Municipality taste like in 2030?”

The students in Sweden acted like talent scouts. They searched the bioregion the for unrealised food-growing potential – people, unused land, forgotten traditions.

One example was a farmer who’s started to grow heritage wheat, but could not find customers.

Another was a school teacher who wanted to connect his students with a working farm, but could not figure out how to do so.

At the end of each year’s course, students pitched their ideas to real-world professionals – for example, chefs, farmers, or food production businesses. Chefs, especially, proved to be effective ‘connectors’ between the course and potential partners.The best ideas were developed with help from Region Örebro’s innovation experts,

The work in Sweden was about the near future – but it also took inspiration from the past. Students explored what we grew 250 years ago – and how – and come up with new ways to connect past and present.

The Swedish grey pea, for example, is a classic but neglected Swedish crop. Peas were a staple crop for millenia before the global food system arrived. Making these staple crops delicious is an important contribution to food resilience.

Dr Magnus Westling, a noted expert on the history and potential future of the pea – worked with a designer, Corina Akner, on humus made with yellow peas.

In the wine business, close attention in paid to the ’terroir’ where a grape is grown – the influence of climate, landscape, soil, and geology on how a wine finally tastes. Magnus Westling wanted us to develop a similar appreciation for cereals, or peas, or potatoes – and our course was part of this innovation.

We also learned that pre-modern Sweden used to have thousands of ‘forest farmers’ – and that tradition is emerging once again. Our students develop new uses for berries, leaves, elk, boar. They persuaded local farmers to try other experiments, too, by growing new kinds of nuts, fibers, and dyes.

Licorice as a destination

In preparation for my visit to Nukus, I read that although most of its agriculture had been decimated by the ecological disaster, liquorice flourishes in salty soils of the dried-up Aral Sea. As The Economist put it in 2022, the region had. become “ the sweet root’s new production hub”. Large areas of degraded and saline land, it was thought, could be revitalised through increased production.

Regrettably, the value of liquorice as an export commodity led to over-harvesting. It was also discouraging, when I arrived, to read advice in a recent German report advised that “ploughing the land and applying fertiliser” would help meet meet demand (Sweet Success in Saline Land A Guise To Cultivating Liquorice In The Aral Sea Region).

Could a way be found to grow liquorice in ways that restore the land, and provide livlihoods for hard-pressed farmers, but without damaging ecosytems even more?

I remembered, at this point, that pastoral people “take their animals to the food, not food to their animals”. Could the same principal apply to humans, too?

Vogue opined recently that Regenerative Farming Is the Latest Wellness Travel Trend. Uzbekistan is home to more than 650 medicinal plant species, among which liquorice is the king pin. Why not develop a new kind of medical tourism and take high-end wellness travelers to where the liquorice grows?

I showed Aral School’s researchers images of Babylonstoren, in South Africa. Once a run-down wine estate, the terroitory now known asthe ‘Versailllles of vegetable gardens”. It now offers a range of food, craft and farming workshops as well as luxury accomodation and fancy restaurants.

The important point here is that agriculture is not just about production and consumption of calories. It also creates ‘public goods’ in the form of social cohesion, public health, territorial development, food sovereignty, farmer livelihoods, learning, innovation, and biodiversity. (Small-scale farmers care for 80% of world’s biodiversity.).

Farming is cultural work that involves time, place, and care — it’s not merely about economic output. Building stronger local agroecological food systems can address intertwined crises of health, climate, biodiversity loss, and precarious rural livelihoods.

Watersheds

Agriculture accounts for about 25% of GDP and employment in in Uzbekistan, and consumes about 90% of all water resources – so water use is a critical priority. Aral School has made it a priority to discover new opportunities, partnerships, tools and collaborations to do with water.

The challenges are severe.The volume of available water in Uzbekistan is forecast to decline by 30-40% in the coming years. And 80% of the ’available’ water, even now, is transboundary. It’s drawn from rivers that other countries have competing claims on, too.

Right now, the focus of policy – shaped by advice from international lenders – is on increased efficiency – but in an economy that remains dependent the export of thirsty commodity crops.

From a bioregional perspective, a “post-irrigation” economy would be preferable. But is such a future plausible?

More to the point, how does one answer the complaint that “you can’t eat bioregioining”?

Bioregioning:

Sounds Nice, but I Need a Job

The government is actively engaged in the search for alternative jobs and livelihoods. Training, reskilling and job-placement support is now provided in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, environmental services, and circular-economy practices.

But in targeting these efforts, priority is given activities of high value economic value. The emergence of non-traditional jobs at a grassroots level get less attention. I don’t blame officials in economy ministries. The livelihoods that attract my attention must look small and insignificant.

But I remain convinced that a big opportunity is waiting to be unlocked. In diverse communities, new urban-rural relationships are emerging . They appear in in a piecemeal, bottom-up way – but they are diverse, and numerous.

In my own work, as a self-appointed talent scout, I’ve come across blacksmithing, outdoor education, learning farms, cooperative grain networks, and many others. I list dozens more in my post Bioregioning: Sounds Nice, but I Need a Job.

Other researchers confirm my conviction that the skills and energy needed for different a just transition already exist in communities the world over. But they are overlooked and unsupported.

What’s missing is a social infrastructure to enable more local people to work in place – an infrastructure which values local knowledge, and treats caring for place as a respected livelihood.

Community-based and small-scale vertical supply chains, for example, have a special potential in Uzbekistan’s food and fiber systems.,

Fiber expert Zoe Gilberston has discovered fibre-based enterprises in several countries in which turning flax seed into cloth, using vertically integrated micro manufacturing processes, is combined with traditional, artisan, hand tool methods. The result is economic activity in which nature, community, meaningful work, and beauty, are combined. “

These community projects can open the door to much wider interests and engagement: says Gilbertson; “they create value beyond the financial”

But they don’t, for the most part, assemble themselves.

Social Ecological Systems

If one theme emerges from 20 years of reseaerch into the Aral Sea disaster, it’s that the ecological catastrophe was multi-layered. Any next steps, it follows, need to be mulit-dimensional, too.

In social-ecological systems, the most effective interventions are multi-level. They address multiple layers of influence simultaneously, Rather rather than focus solely on individual behaviours, holistic strategies recognize that changes at one level can reinforce or undermine others, leading to greater sustainability and impact.

Efforts to reduce sedentary behaviour in children are a good example. When interventions were targeted four levels – intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, and community – effectiveness rates of up to 78% were achieved. compared to single-level interventions such as a focus on individual education or awareness.

Single-point interventions, we now know, often fail due to resistance from other system components, connected by by interdependence and feedback loops. T

Now: For “child” read “place”.

As with children, the optimal development and well-being of place involves of networks of people and structures. To get there, from here, diverse actors and stakeholders need to be involved.

Culture is infrastructure, too.

Healthier relationships between people and their places are as much cultural as practical. Emotional, ethical and cultural connections are needed, between people and place, that foster belonging, responsibility and care.

I told a story from Scotland – 5,500 kilometres away – to demonstrate that these cultural connections can and are being be repaired and revived.

Nature recovery is urgently needed in the Scottish Highlands. Centuries of ecological degradation have resulted from deforestation, overgrazing and land use practices that diminished biodiversity and disrupted natural systems. To reverse that trend, the Findhorn Watershect Initiative is a multi-generational vision to restore a mosaic of nature rich habitats, grow a local culture of nature connection and enable a thriving nature-positive economy for the people and places of the River Findhorn’s watershed area.

Working as Human Ecology Researchers-in-Residence, McFadyen and Sandilands explored how Gaelic cultural heritage can rekindle nature connection, guide restoration efforts, and foster relationships of care for lasting stewardship. Sandilands and McFadyen explored maps, interviewed local people, and delved into archives, to discover how Gaelic place names, stories and songs connect the culture and ecology of the Findhorn River.

Their work demonstrated how Intangible Cultural Heritage – place names, creative cultural expressions and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)- can repair damaged relationships between people and place, and support place-sensitive nature recovery that is inclusive, forward-looking, and adaptive.

“Integrating Intangible Cultural Heritage in nature recovery: a place-sensitive approach in the Scottish Highlands” by Mairi McFadyen, Chris Mackie, Elle Adams and Raghnaid Sandilands

inkedin.com/posts/thackara_findhorn-river-connections-human-ecology-activity

Bioregion as classroom: my Aral School takeaways

The people of Karakalpakstan have lived with ecological collapse for generations. They continue to do so – with remarkable grace and determination. They are not waiting, now, for more research about its causes, homilies about resilience, or implausible quick fixes.

Rather, looking ahead, the region’s story “will be written by the communities at the forefront of adaptive design, scientific inquiry, and cultural reinvention” – as stated by Gayane Umerova, Chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation.

Jan Boelen invited me to Aral School to talk about bioregioning and health – and the way he describes the opportunity also rings true with me: “Bioregioning is less about redefining borders than it is about reconnecting to the local landscape and – perhaps even more – creating a network of relevant knowledge.

Seen (and practiced) through that lens, bioregioning is neither a blueprint, nor a method. It’s a set of values to guide constantly evolving actions in unique and complex contexts.It’s about embodied relational understanding. It’s a way of knowing, and being, that’s contextual, holistic, and attentive.

My visit to Nukus confirmed my conclusion that health and wellbeing – in a place, as in a person – are not something you ‘deliver’, like a pizza. The delivery word perpetuates the myth that health is something produced by one set of people [the professionals] for another [their customers]).

But Aral School is not in the delivery business. Health and wellbeing are properties of social and ecological systems. The desired outcomes of its work are healthy social, ecological and economic systems.

Many of the skills and energy needed to achieve these outcomes are already out there. What’s needed are new kinds of social infrastructure to enable collaboration. These social infrastructures are hybrid: analogue, but supported by digital tools and platforms.

Intangible cultural heritage is far more than a visitor attraction. It’s a medium of reconnection and healing. Looking ahead, one of the most important keywords is #envhist

Disaster tourism (‘dark tourism’) is over. My visit to Aral School was of the new kind.