A chapter for the catalogue of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2002, edited by Deyan Sudjic (who was also overall Director of the event).

A few years ago I met a woman in Bombay who was completing her PhD in social anthropology. She had just returned from her last field trip to Rajhastan where she had spent time with a group of travelling storytellers. This particular group went from village to village, unannounced, and would simply start a performance in the village square. Although each story would have a familiar plot the story telling tradition dates back thousands of years ˆ each event would be unique. Prompted by the storytellers, who held up pictorial symbols on sticks, villagers would interact with the story. They would be part of the performance. I commented to the woman that with that depth of knowledge about interaction, and the combined use of words and images, she could get a job with Microsoft tomorrow. ‘What’s Microsoft? ‘, Was her reply.

This encounter confirmed my prejudice that we have forgotten how to design for communication and interaction. We know how design messages, yes: the world is awash in print and ads and packaging and e-trash and spam. And we know to design one-way-communication buildings: hundreds of sports stadia, museums, theatres, science and convention centres have been built in recent years. Most of these buildings do an adequate technical job in delivering spectacles to passive crowds – but they are all about one-way messages. In the open air, as in the Indian villages my friend described, people cluster around a speaker. Children wriggle through to kneel at the front. As the crowd grows, the more distant and adventurous will seek a higher vantage point tree, rock, wall, or balcony. The courtyard form of theatre evolved from there and remains the root form for most later theatrical development. It simply grew in size and sophistication. Today’s monumental, overblown and inhospitable theatre and arena architecture is the creation of a point-to-mass mentality that lies behind the brand intrusion and semiotic pollution that despoil so many of our perceptual and physical landscapes.

A lot of the push towards a post-spectacular culture – perhaps surprisingly – comes from business and technology. The chicken breasts in my supermarket have started to bear a photograph of the farmers who rear the birds, plus a little story about their place. Globalisation promoted ‘anytime, anywhere’ as a value – but attention is shifting back from space to place. Even telecommunication companies see location as the next big thing. The new business thinking is that mass things – mass production, mass communications, and large public spectacles – are relatively easy for upstart competitors to copy. Abuzz with talk of closed and open systems, large firms now believe that the best way to compete is by making things more complicated, not less. Complex services, and customised experiences, will be harder for newcomers to imitate. Business has decided that there’s money to be made in customisation and authenticity. The idea is to make a real-time ‘now economy’. Vivek Ranadive, author of the power of now, has a rather precise vision of what he calls the “event-driven firmâ€. Business is also responding to spectacular erosion in brand loyalty, which calls into question the fundamentals of modern marketing.

A similar change of mood is evident in the traditional worlds of performance. In theatre, for example, big is over. Big concepts, big-ticket productions – and the big marketing budgets needed to make them pay – are out of favour. Tony Graham, Director of the Unicorn Children’s Theatre in London, looked at more than 100 buildings in London before deciding to commission a new theatre on the River Thames. “Scale is crucial in theatre” he says; “300-400 people is the maximum size at which you can be both epic and intimate, and we simply could not find a space that would allow us to those in the way we need to do”. A 1500 person audience creates a differerent sense of what theatre is about. Prosaic issues to do with access play an important role: where do coaches park, how far is it to the tube, and so on. But. Graham’s brief to Theatre Projects, who lead the functional design of his new theatre, was to move away the proscenium arch model, with its picture-book illusion of looking into a room. “We are moving back to the amphitheatre model which thrusts the stage into the body of the audience”, says Graham; “audiences today don’t want trickery, special effects and illusion. They want to see things as they are, without artifice”. The amphitheatre model favoured by Graham “heightens the human figure and strips things back to the minimum”.

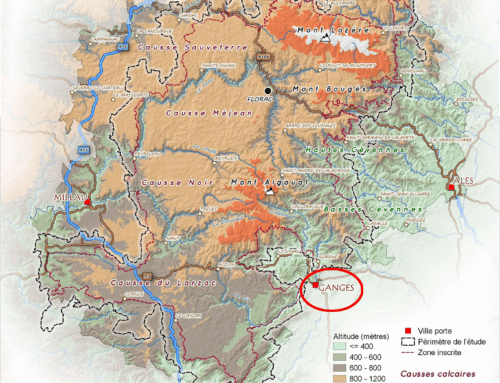

Many in the theatre world question whether new buildings are needed at all. Big theatres, in particular, tend to sap energy out of productions and money out of their producers. Some producers have taken literally to the streets in so-called ‘promenade’ and site-specific theatre. In these Chaucer-like journeys, players and audience move together around cities, through forests, up mountains, or into resonant but abandoned or found spaces. The significance of place, and the localisation of knowledge, is now taken as seriously by companies as by theatre people. As John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid emphasize in The Social Life of Information, a lot of what we learn is remarkable local: History. Agriculture. Politics. Art. Geology. Viticulture. Forestry. Conservation. Ocean Science. For the writer Charles Hampden-Turner, too, we learn through participation in collaborative human activities. “Knowledge as it grows is necessarily social,” he writes, “the shared property of extended groups and networks”.

What matters most in a post-spectacular world is activity, not architecture. As the director Peter Brook once said, it is not a question of good building and bad; “a beautiful place may never bring about an explosion of life, while a haphazard hall may be a tremendous meeting place. This is the mystery of the theatre… studying what it is that brings about the more vivid relationships between people.” In biology, they describe as choronomic the influence on a process of geographic or regional environment. Choronomy adds value; a lack of context destroys it. We all deserve to spend time in safe, pleasant and comfortable surroundings, rather than their opposite; but, beyond that, most buildings will surely do – for performance, for learning, for all forms of social connection.

Given that more space is needed for shared learning activities, many involving performance and interaction, where will it come from – and who will pay for it? Happily, large, expensive, centrally located informal environments, suitable for learning and performance, already exist in most cities in the form of museums, science, and media centres. The majority of these facilities were conceived and are now run as leisure facilities, spectacles for public and tourists who only ever visit them once. These buildings are therefore ripe to be commandeered and re-purposed as sites of informal learning.

Some of their Directors are eager for such a change. James Bradburne, for example, Director of the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Frankfurt, despairs that exhibition design ever since the 1950s has been “obsessed with the message – the storyline – and has seen itself as one of the broadcast media, reaching out to the masses with its messages”. The apotheosis of this approach is the Guggenheim, whose director, Thomas Krens, turned the Guggenheim into a theme-park-like franchise operation and that now competes with Disney for the property and leisure developer’s dollar. The word ‘exhibit’ is at the heart of criticisms of the museum and science centre model where, once again, a point-to-mass model of communication prevails.

Instead of looking at the design task as creating exhibits, modernisers like James Bradburne have shifted their focus from the exhibit as an end-in-itself to the exhibit as a setting for interaction between and among participants: discussion, dialogue, debate are the goal. Just as with theatre. At NewMetropolis in Amsterdam, where Bradburne’s ideas were first implemented, the emphasis was not on science and technology, per se, but on being human beings in a world rapidly being transformed by science and technology. “Our aim was to foster skills of experimentation, abstraction, collaboration, and systems thinking”, says Bradburne, who led the design team there before moving to Frankfurt. Puzzles, challenges, simulations and role-playing games were at the heart of his design strategy. “Our goal was to stimulate self-initiated exploration, encourage sustained engagement, and repeat use, and provided a framework in which competence demonstrably increases”. Bradburne uses the metaphor of the piazza – in contrast to the arena – to describe this kind of museum as a resource to be used, rather than visited, or looked at.

The best collaboration environments provide the opportunity to meet, share ideas, discuss, and learn from each other’s experiences. Seen in this way, anyone who plays a role in shaping a learning or performance environment – whether they are by training a researcher, a teacher, a multimedia specialist, a programmer, or an industrial designer – is a designer. Design must allow the user the shape her experience. “Design doesn’t end with the opening”, says Bradburne, “it begins with the opening”.

Theatre and museum people are not alone in their search for a more rooted, animated context in which to work. Richard Sennet once complained, „When public space becomes a derivative of movement, it loses any independent experiential meaning of its own. On the most physical level, these environments of pure movement prompt people to think of the public domain as meaningless… It is catatonic space‰ The word catatonic is horribly apt as a description of the way many great modern spaces make us feel – arenas and stadia designed for passive crowds, as much as airports and hub wastelands such as Eurolille.

The problem is not new. Throughout the twentieth century artists intervened in a variety of ways into man-made space: futurism, cubist collage, Duchamp‚s ready-mades, Dada, constructivism, surrealism, Fontana‚s spatialism, Fluxus, land art, arte povera, process art, conceptualism: in all these groups the deadness and catatonia of modern public space were perceived to be both as a rebuke, and a challenge. They prepared site-specific installations and events whose meaning was to be gathered by the viewer over time. (Performance art itself was born in a fistfight in 1910 between Italian Futurists and Venetian townspeople reacted in anger when 800,000 manifestoes “Against Past-Loving Venice” were scattered upon them). The tradition has persisted that, in Marinetti’s words, “there is no artifice here: this is happening now, in real-time”.

Today, even real-time is mediated. In the age of the rave, street-level events have become big productions. Festivals, concerts, corporate events, church pageants, and fashion shows vie with each other tin the quality and sophistication of their production. The supply and use of technology for live performance is a large speciality business in itself: hundreds of companies specialise in every conceivable variety of lighting, sound systems, staging, video walls, and endless special effects. The rapid evolution of digital media, advanced materials and other technologies has further opened the way for technology to penetrate live performance. The design and evaluation of alternative musical and lighting controllers is currently the leading edge of an ongoing dialogue between technology and musical culture

It is not just real-time performance that is mediated. So is “here”. With the advent of broadband video, satellite and wireless, and fixed networks, live performance has entered the realm of the reproducible and in the words of one critic, “barriers between the televisual and the performative are breaking down”. The human actor who shares the same space and time with a body of spectators can now, to a degree, share other spaces and other times with different actors – in so-called electronic arenas in which spatial technologies, especially multi-user virtual environments, are coupled to new forms of artistic content and an understanding of social interaction.

But even in virtualised, networked contexts, the cultural drive is to support interactive performance and interaction, not passive spectacle. A European project called eRENA, for example, investigated a range of inhabited information spaces in which participants would be mobile and socially active. Audience members as well as performers and artists would explore, interact, communicate with one another and participate in staged events. Through concepts such as ‘dynamic crowd aggregations’, the aim was to support hundreds or thousands of simultaneous participants, bridging the gap between current small scale, real-time communication technologies such as video conferencing, and current massive-scale non-participative broadcast technologies such as television. The Erena consortium brought together digital artists, experts in multi-user virtual reality and computer animation, social scientists, broadcasters, experts in expertise in CAVEs and other projected interfaces, networking expertise, spatial technologies and novel artistic content. Avatars, both as individuals and in potentially large and dynamic crowds.

The point-to-mass age of big ticket spectacles is ending. We are in a transition to a post-spectacular, post-massified culture in which performance environments will be judged by their capacity to foster interaction and learning. The trend is towards spaces, places, and communities in which complex experiences and processes combine in new geographies of learning and experience – while also exploiting the dynamic potential of networked collaboration. A division persists between designers who believe that experiences can be systematically designed, and those who feel that the designer can only set the stage for what is experienced – but the consensus is clear: we are all actors now.