Packaged mass tours account for 80 percent of journeys to so-called developing countries, but destination regions receive five percent or less of the amount paid by the traveller. For local people on the ground, the injustice is absurd: if I were to pay e1,200 for a week long trek in Morocco’s Atlas mountains, just e50 would go to the cook and the mule driver who do the work. The mule, who works hardest, gets zilch. Can green travel be reformed?

The green cup I’m holding (above) contains elderflower cordial, freshly-made by the nuns who live in a 16th century convent in Wernberg, Austria. One of their number, Sister Monika-Maria, has guided us barefoot on a circular “Path of Consciousness” over the lush Carinthian meadows you see in the background. Every few hundred metres, we stop for a short discussion about man’s changing relationship with nature.

Back in the convent’s enormous herb-garden (below), one of Sister Monika-Maria’s colleagues helps us gather armfuls of fresh herbs.

We sprinkle these onto the cheese (below) that comes from the nuns’ cows and is spread on the fresh-baked bread made from wheat they also grow themselves.

Back at the conference (I am in Austria with 300 travel industry professionals) I learn that Wernberg is just one among a growing number of green locations in this part of Europe that can be visited along the a 785 km hiking route called the Alpe-Adria Trail. The trail (below), which follows paths developed by walkers over hundreds of years, spans three countries.

In one of these adjacent countries, Slovenia, a small firm called Apiroutes organises holidays only about bees and bee keeping. Slovenian beekeepers are known to be especially healthy, I am told; they can live to a ripe old age and “retain their physical energy and clarity of thought to the very end”.

Reaching for my diary, I am torn between a two-week bee-keeping walk along trails once trodden by pilgrims (below); an apitherapy study camp; or a course in in an api brewery on how to make honey wines.

So green tourism is alive and thriving, right? In Austria and Slovenia the answer seems to be yes – but elsewhere in the world the situation is gloomier.

The travel industry professionals I met in Austria seemed united in their wish to replace a model of mass tourism that has seen coastlines concreted over from Spain to Mexico. They mention the absurdity of a model in which a tourist from a rich country can use as much water in 24 hours as a someone who lives there uses in 100 days.

Above all, they would like to see change an industry that perpetuates social inequity.

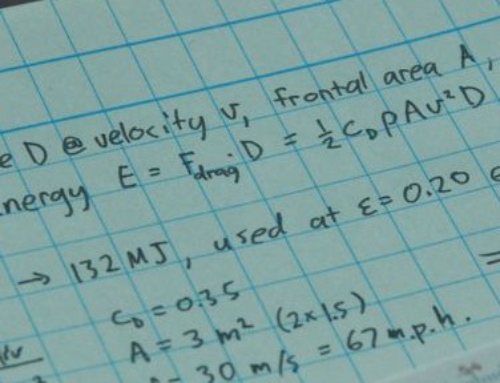

Package mass tours account for 80 percent of journeys to so-called developing countries, for example, but destination regions receive five percent or less of the amount paid by the traveller; 20 percent on average remains in the country of origin, 37 percent goes to the airline, and local intermediaries and investors take a substantial cut of what’s left.

For local people on the ground, the injustice is absurd: if I were to pay $1,200 for a week long trek in Morocco’s Atlas mountains, just $50 would go to the cook and the mule driver who do the work. The mule, who works hardest, gets zilch.

It emerged at our conference in Austria that awareness of the problems with mainstream travel is not an issue. As I learned from our host, Dr Petra Stolba, most of the world’s travel agents have heard about sustainable tourism, and 70 percent of travellers would consider a green option when planning a trip.

Shared misunderstanding

The trouble is that there’s no shared understanding of what sustainable tourism actually means. On the contrary: a bewildering variety of words and labels is a guarantee of confusion. Thousands of green-coloured websites talk about Sustainable Tourism, Responsible Tourism, Slow Travel, Nature Tourism, Green Tourism, EcoTourism.

Many travel operators proclaim their support for the 2001 Cape Town Declaration on Responsible Tourism – but the barrier to adherence is low. Supporters need commit merely to ‘minimise’ negative economic, environmental, and social impacts. There are no binding targets, no governance of this vast and fragmented industry. As one critic put it, the result is an empty promise to leave the world ‘As Unspoilt As Possible’.

Many travel operators, aware that labels on their own have become meaningless, advertise the fact that their travel products are verified, accredited, or certified as being sustainable. But, as with the confusing language, so many competing standards have been introduced (below) that the effect is to cancel each other out . The injustice is compounded by the fact that genuinely conscientious independent operators lose their hard-won advantage.

In some regions of the world, the realization that the word “ecotourism” sells has made things worse. In Central America, for example, an ecotourism label only rarely means that local people are involved in planning and running projects, or that measures are taken to reduce environmental impact. On the contrary: as the French writer Anna Vigna discovered, nature is being ruthlessly exploited and sold. “The methods have hardly changed from when Acapulco was over-developed 40 years ago,” she writes; “authorities are corrupted, information kept secret, derisory sums (if any) are paid for land, and social and ecological consequences are systematically ignored”.

P2P to the rescue?

There was keen interest, in Austria, in the prospect that peer-to-peer e-tourism, enabled by the internet, might make a real difference.

The internet has certainly transformed the range of travel options available, and enables travellers to exchange notes and ratings.

These features have helped AirBNB, for example, become the largest hotel gateway in the world after just four years in business. Further down the budget ladder – and causing further anxiety to the big hotel chains – other newcomers include WeHostels (one up from CouchSurfing) and, for those who don’t even need a roof, Campinmygarden.com; the latter offers private gardens as micro-campsites.

The P2P guided tour – by some accounts a $24bn market in its own right – is also evolving. Among a flock of new entrants: SideTour lets you buy “small experiences” around the city, such as dinner with a monk; LocalMind, recently purchased by Airbnb, enables you to “find out what’s happening right now in a place that interests you”; Get Your Guide brings you “things to do, all over the world”; Vayable promises “unique trips and adventures curated just for you”; Sidetour challenges its visitors to “Do Something Memorable”; HipHost, likewise, puts you you in touch with friendly local hosts who create all manner of “fun things to do”.

These sites are very me-too, of course, but Jeremy Smith, a noted P2P travel innovator, reckons that the old tour guide model of “pay us and we will show you the strange foreigners” is on its way out. Peer-to-peer, he says, is the perfect model for the ever-growing numbers of us wanting the chance to “share knowledge and co-create experiences that are more rewarding for us all.

Well, maybe. My own take is that while resource-sharing for travellers is cool, it is not, per se, green.

Most of the new internet platforms empower the traveller, but not the destination. Their pitches to potential investors, for example, are filled with the language of mass tourism: “destination”, “product”, “targeting”, “the travel space”, “locals”. It’s not that these start-up kids are evil: As an investment opportunity, the P2P model has to deliver large numbers of transactions. But the fact remains that unique, respectful and equitable relationships between hosts and visitors are described dismissively by investors call ‘lifestyle’ features: Nice, but peripheral.

From object, to subject

Twenty years ago, when the concept was first mooted, many people hoped that community-based tourism and ecotourism could be the basis of a new relationship between visitors and their hosts. I believe there are three reasons these hopes have not been realized:

The first is that tourism, at its heart, is a form of consumption – and will remain so. We pay for an experience, not for a living relationship. Why else would the industry describe the communities we visit as ‘destinations’ or ‘products’?

Second: A commitment to “do less harm” has little meaning in a business that keeps on growing. On the contrary: Compound growth leads unavoidably to the occupation of untouched places. The catastrophic floods in Uttarakhand state last week, for example, which claimed 1,000 lives and obliterated a biodiversity hotspot filled with unique flowers, have been blamed on the overdevelopment of roads to carry tourists (along with too many hydro projects).

A third dilemma is that tourism, however green, can never bring about environmental and social justice on its own. If biodiversity and social justice are to thrive, all the economic and social actors in a bioregion need to collaborate – with its long-term health as their shared goal. A fragmented global industry – especially one whose major actors are rootless multinationals – can never be a means to that end.

These challenges may seem immense – and they are – but people and communities everywhere are learning, and adapting.

Among environmental and climate change activists, for example, a consensus is emerging that the time has come to move beyond the “do less harm” language of resilience, mitigation, and adaptation. There’s a widespread sense that, in all our projects and innovations, we need to commit to leave things better.

In the travel ecosystem, too, the impressive growth of platforms such as WWOOF (it stands for World Wide Opportunities On Organic Farms), HelpX, and the francophone Mission Culture & Communauté is evidence that many young people want to contribute physically to the growth of organic farming. These sites list organic farms, ranches, and lodges that invite volunteer helpers to stay with them and work in exchange for food and accommodation.WWOOF, which is attracting 100,000 new members a year, represents 14,000 farms in more than 50 countries. The network is beginning to organise itself along what I choose to perceive as bioregional lines: In Sweden, there are plans to have a WWOOF representative in each of the country’s 25 regions by the end of the year.

Elsewhere, elders from the worlds of government and business are discarding their suits to go on learning visits that expose them to the profound value of local wisdom and traditional knowledge. European citizens are taking up Fair Trade Walking to accelerate the adoption of more equitable trading relationships between the rich North and the long-exploited South. Ecomuseums are being established in Ecuador, France, China, and Slovenia.

In these and many other small but significant ways, travel platforms and projects are emerging that exemplify a new narrative of living relationships, of reciprocity, of connectedness.