The future of the car has been electric for what? Five years now? ten? The answer is 110 years, for it was back in 1899 that La Jamais Contente (“The Never Satisfied”) became the first vehicle to go over 100 km/h (62 mph) at Achères, near Paris.

Since then, as we produced hundreds of millions non-electric cars – and despoiled the biosphere in the process – all manner of non-petrol cars, including electric ones, have come and gone.Tesla in the the US and Norway’s Think are just the latest in a long line of newcomers.

They, too, will fail to break the grip of the gas guzzler for one reason: they do not challenge the production system and business model of an incumbent global industry that is so mature that it can only make incremental changes as new pressures arise. Electric cars such as Tesla fall into this category: they are an incremental improvement, not a replacement for an ecocidal global industry.

This writer has long been sceptical that small private vehicles would have an important role to pay in a sustainable mobility mix. But Riversimple has made me pause for thought.

At a presentation in Leicester, UK, last month, where a deal has been struck with the City Council for 30 vehicles to be piloted there in 2012, we were told that the formal purpose of this new start-up is “to build and operate cars for independent use whilst systematically pursuing elimination of the environmental damage caused by personal transport”.

Not reduce but *eliminate* environmental damage? How could that be possible?

The company’s founder, Hugo Spowers, explained that every aspect of the company’s operation – not just its vehicle technology – is based on whole system design. It has evolved from a linear resource-consuming model, in which natural capital resources are not replenished, to a cyclical system in which waste streams provide all material inputs, and all loops are closed.

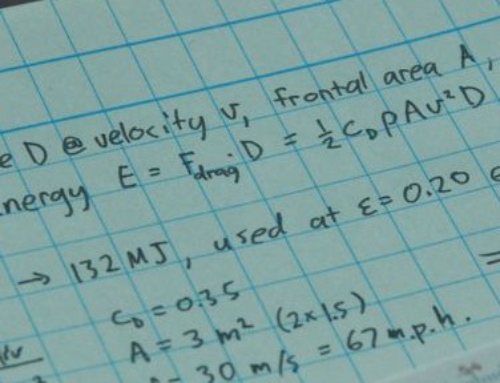

The car itself has five novel features: a composite body, four electric motors, no gearbox or transmission, regenerative braking, and power provided by hydrogen fuel cells. Its Network Electric Platform has been so designed that if there are breakthroughs in other power sources, these can easily be incorporated later on. The vehicle is decoupled from a single power platform or refuelling infrastructure.

But Riversimple’s technology is just the start. Its cars will not be sold outright. Customers will buy mobility as a service rather than a car as a product. There will be no maximum or minimum mileage allowance and, critically, it is a fully bundled service covering all costs such as road tax, vehicle maintenance, insurance and fuel, with no surprises to the customer.

The way the system has been designed, it is in everyone’s interest to keep cars on the road as long as possible. Riversimple will be the first car manufacturer for whom success will not mean persuading you to buy a new one every three years.

Customers will interact with Riversimple and its user community through a personalized digital interface accessed from the car, on their computer, or via their mobile phone. They will be able to manage their account, request maintenance, ask questions, locate the nearest refuelling station, and so on.

To ensure that energy and resource efficiency remain at the heart of everything the company does, lower environmental impact is financially rewarded.

A sale of a service model is therefore pushed upstream into the supply chain. The supplier of the hydrogen fuel cell, for example, is likely to remain its owner. Manufacturer and supplier thereby have a shared interest in the longevity and reliability of the vehicle, and of the system as a whole.

Riversimple’s production model, too, is distributed. Its carbon composite bodies allow profitable manufacturing with plants producing 3-5,000 units each year. This regional distribution of production will enable the delivery of improved service for regional markets at reduced cost. [The company is in early stage discussions with other regions across the world to roll out this strategy through joint venture partnerships for local manufacturing facilities]

The next consideration is service. An urban car is effectively tethered to its home city, so the critical scale for establishing a commercial market is that of a city, rather than a nation. Riversimple’s service infrastructure, too, is cellular – city by city.

The surprises continue. Everything in RiverSimple is open source. The company is adopting an open intellectual property model, based on that used in open source software. The design of this and future vehicles will be shared, thereby allowing anyone to collaborate in the design and build of our cars under an open source licence.

Riversimple, as one producer among many, believes this will be a fast route to replacing the internal combustion engine.

The aim is to maximise design input from passionate experts at low cost. It is therefore also licensing its technology to the open-source foundation 40 Fires. Riversimple wants people to contribute to the design in the same way computer programmers help build Unix.

The company is owned by six “custodial bodies”. Among these is Environment – on an equal footing with investors and commercial partners. Checks and balances are built into the system through the appointment of a Stewards body, who are responsible for auditing and monitoring the governance.

The structure and responsibilities of conventional corporations create a confrontational dynamic with most stakeholders Therefore shared ownership is another key feature of the Riversimple system. Its ownership model is inspired by long-standing and successful businesses such as VISA International, John Lewis Partnership and Mondragon. All stakeholders have a formal role in the organisation, to all parties’ benefit.

Is RiverSimple another design-studio concept? Hardly: The family of Ernst Piëch, part of the dynasty who founded Porsche, is the current major investor.

Oh, you wanted to see the car? Here it is: