[A new book from the Dutch publisher Bis, Open Design Now, includes essays, cases and visuals on various issues of Open Design. The book contains practical guidelines for designers, design educators and policy makers to get started with Open Design. It also includes a preface, contributed by me, that is reproduced here].

In 1909, Peter Kropotkin was asked whether it was possible to learn a trade so difficult as gardening is, from books. “Yes, it is possible” he replied, “but a necessary condition of success, in work on the land, is communicativeness – continual friendly intercourse with your neighbours”.

Although a book can offer good general advice, Kropotkin explained, every acre of land is unique. Each plot is shaped by the soil, its topography and biodiversity, the wind and water systems of the locality, and so on.

“Growing in these unique circumstances can only be learned by local residents over many seasons” the aristocratic anarchist concluded; “the knowledge which has developed in a given locality, that is necessary for survival, is the result of collective experience.”

The biosphere, our only home, is itself a kind of garden – and we have not looked after it well.

On the contrary we have damaged many of the food and water systems that keep us alive, and wasted vast amounts of non-renewable resources.

One of the main reasons we’ve damaged our own life-support system is that we under-value the kinds of socially-created knowledge Kropotkin wrote about. Ongoing attempts to privatize nature, and the over-specialization of knowledge in our universities, continue to render us blind to the consequences of our own actions.

Open-ness, in short, is more than a commercial and cultural issue. It’s a survival issue.

Systemic challenges such as climate change, or resource depletion – so-called ‘wicked problems’ – cannot be solved using the same techniques that caused them in the first place.

Open research, open governance, and open design are a precondition for the continuous, collaborative, social mode of enquiry and action that are needed.

For centuries, the pursuit of knowledge was undertaken in open and collaborative processes. Science, for example, developed as a result of peer review in an open and connected global community. Software, too, has flourished as a result of social creativity in what Yochai Benckler has named ‘commons-based peer production’.

These approaches stand in stark contrast to the legacy industrial economy – from cars, to power stations – which depends on a command-and-control business model and miitant copyright protection.

The internet may have made it easier, technically, to share ideas and knowledge – but an immense global army of rights owners and attendant lawyers works tirelessly to protect this closed system of production.

The open design experiments you will read about in this book – such as the 400 fab labs now in operation – are nodes within an alternative industrial system that is now emerging. These are the “small, open, local and connected” experiments that, for the environmental designer Ezio Manzini, are defining features of a sustainable economy.

Open design is more than just a new way to create products.

As a process, and as a culture, open design also changes relationships among the people who make, use and look after things.

Unlike proprietary or branded products, open solutions tend to be easy to maintain and repair locally. They are the opposite of the short-life, use-and-discard, two-wash-two-wear model of mainstream consumer products. As you will read in the book, “nobody with a MakerBot will ever have to buy shower curtain rings again”.

Another open source manifesto states, “Don’t judge an object for what it is, but imagine what it could become.” This clarion call is welcome – but it does not promise an easy ride for open design.

Our world is littered with the unintended outcomes of design actions – and open design is unlikely to be an exception.

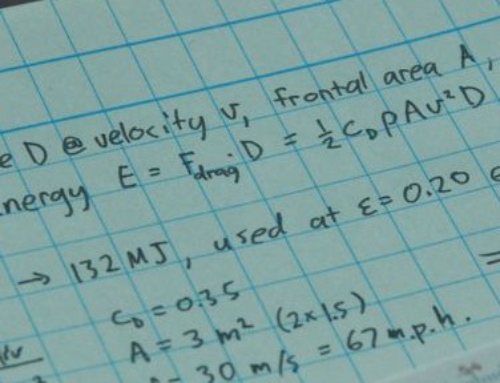

For example, ninety percent of the resources taken out of the ground today become waste within three months – and it’s not axiomatic that open design will improve that situation.

On the contrary, it’s logically possible that a network of fablabs could fab the open source equivalent of a a gas-guzzling SUV.

The long-term value of open design will depend on the questions it is asked to address.

An important priority for open source design, therefore, is to develop decision-making processes to identify and prioritise those questions. What, in other words, should open designers design? All our design actions, from here on, need to take account of natural, industrial and cultural systems – and the interactions between them – as the context for our ceative efforts.

We need to consider the sustainability of material and energy flows in all the systems and artifacts we design.

In reading the texts that follow in this book, I am confident that these caveats will be embraced by the smart and fascinating pioneers of open design who are doing such fascinating work. Crowds may be wise – but they still need designers.