Some people blame the Enlightenment for our present troubles.

The scientific revolution, they say, gave man ideas above his station. We frequently harm natural systems, goes the charge, because of our delusional belief that we are separate from, and have dominion over, nature.

This myth of apartness, the charges conclude, dulls the responsibility we’d feel if we felt ourselves to be co-dependent members of natural community.

History suggests that modernity is not uniquely to blame for messing with Gaia.

During his reign as King of Sri Lanka from 1153–1186, for example, Parakramabahu asserted that “not even a little water that comes from the rain must flow into the ocean without being made useful to man”. He went on to construct or restore of 165 dams, 3910 canals, 163 major reservoirs and 2376 minor tanks – all in a reign of 33 years.

Parakramabahu started a tradition whereby every Sri Lankan king would build dams; the island now contains more than a thousand. No country in the world contains so much man-made irrigation per square km.

True, many of the eighty largest ones were built by foreign contractors using international development finance; today, these mega-projects would probably be frowned on. But the most intense – and indeed sophisticated – fiddling by man with nature took place 1,000 years ago.

Green factories

I learned about King Parakramabahu during a visit last week to a bra and panty factory in Sri Lanka – MAS Intimates Thurulie – which is one of the greenest factories in the world.

Almost as impressive as the rainwater capture tanks, cement stabilized bricks made of local materials, anaerobic digesters, and water-saving sculpted landscape, was the fierce competiton between rival manufacturers MAS (where I went) and Brandix to prove to us visitors that its factory was greener that the other’s.

More than a million people (out of population of 20 million) work in Sri Lanka’s fashion industries, so it’s critical to the whole economy. Companies have to contend with two pressures: One one side are powerful foreign buyers such as M&S (the MAS factory’s sole client), Tesco, and Victoria’s Secret. (The latter’s buyers tend to arrive in large helicopters).

Sri Lanka’s industry must also contend with competition from other fashion producing countries, from Turkey to Bangladesh, that also need to support hundreds of thousands of small and micro businesses. The big global buyers can and do switch production from one country to another at a moment’s notice if they deem it necessary to do so for competitive reasons.

Squeezed like this, it’s no small matter that Sri Lanka has resolved to compete on the basis that it’s companies are ethical and sustainable, not just cheap. A centrepiece of this strategy is Garments Without Guilt.

But how to proceed? This was the question posed by the Sri Lanka Design Festival to an International Symposium on Ethical Fashion.

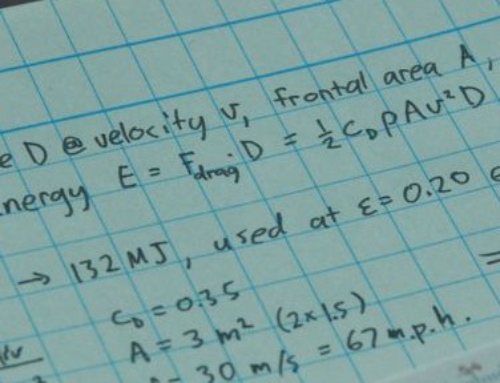

Here below is the text of my 30 minute contribution.

] Fashion in a green economy

] John Thackara speech Sri Lanka Design Festival 30 November 2009

I will talk today about the emerging green economy – its ethical basis, and in particular the unique opportunity for Sri Lanka to become a model that can inspire and teach the rest of the world.

I will talk about the concept of clean growth – and whether it is, or is not, a contradiction in terms.

I will conclude with some practical suggestions about how to innovate for sustainability – especially when the fashion buyer has so much power, and when the interests of so many different stakeholders need to be aligned.

Our situation today is uniquely challenging. Financial collapse. Peak oil. Climate change. Insecure food systems. Each of these challenges is daunting on its own. Taken together, they surely mean that business- as-usual is over – for good. The old ways will not return.

Yes, there are “green shoots” – but they are not the same old plants. They are the first sign that new economic and social life forms are emerging: social and business arrangements quite unlike what we have all known until now.

What your overseas visitors have seen over past few days suggests strongly to me that Sri Lanka has the potential to be one of these new life forms.

Globally, we have arrived at what complexity researchers into complex systems call an “inflection point” – a tipping point. After forty years of talk and prevarication about what needs to be done, of putting off inevitable change, I believe our instinct for survival is finally taking hold.

I say survival, because the existing economy – the economy in which Gross Domestic Product is the only measure of success – has become, in the words of the True Cost campaign, a “doomsday machine.” It is programmed to grow to infinity in a biosphere whose carrying capacity is finite.

The fashion industries have not been immune from the madness of chasing growth: More and more collections every year, regardless of the costs and consequences.

Many people in this room are more expert than I am on issues to do with pesticides, dyes, water, energy, and waste. We all know what the problems are.

But let’s not beat ourselves up unnecessarily. Fashion is no worse than many other industries in its introspection, and disregard for the bigger picture.

The information technology industry is notorious for looking only inwards inside its tent. The car industry, likewise. Aviation? totally in denial. Sustainability advocates with names like John who fly around the world? Not much better.

Our subject today could just as easily be food. Thanks to four decades of innovation and modernisation, the world’s food systems are twelve times less efficient today, in terms of energy and energy out, than they were when I was a child.

Food systems are a main cause of the global obesity pandemic. As today’s obese children get older, and develop diabetes and heart conditions, their sickness threatens to overwhelm health services of advanced countries. At least fashion is not to blame for that!

Whether it’s food, or fashion, or shelter, or transport, all the systems by which we organize daily life so badly are symptoms of a structural problem: they operate within an economy whose only measure is money.

What does not get measured, tends to get forgotten – and then, concreted over. GDP does not take important aspects of our societies into account: neither the informal sector, nor the well-being of populations, nor the health of ecosystems.

It’s madness. And the world is waking up to the fact that it’s madness.

A couple of weeks ago, for example, the economist Lord [Nicholas] Stern gave a talk at the People’s University of Beijing.

Stern, a key architect of the global status quo, stated the unthinkable: “we have to question whether we can afford future growth”.

Can’t afford to grow! What an extraordinary thing for a former World Bank chairman to say! Even its most ardent former advocates, in other words, believe the basic operating system of the global economy is broken

.

But wait a minute: the basic premise of the global economy is perpetual growth without thought about its impacts on the biosphere. Who knows how to operate economically under such constraints?

The countries that are not yet wrongly-developed, that’s who knows.

For the last 30 years, the word development has been used in this sense: that advanced people in the North must help backward people in the South catch up with their own situation.

Hmmm.

But consider this: the average US citizen emits as much CO2 in one day as someone in China does in over a week, or a Tanzanian in seven months. Or this: a tourist to Mali from a rich country uses as much water in 24 hours as a villager who lives there uses in 100 days.

Big D development – top-down, outside-in development – tends to view human, cultural and territorial assets – the people and ways of life that are already there – as impediments to progress and modernisation.

The development industry – which is what it has become – measures progress, in other peoples’ countries, in terms of growth and increased consumption. Big D development tends to devalue human agency and existing contextual knowledge. And it often seeks to replace people with technology, automation and “self service”.

Automation? In a world with six billion people and rising?

Very smart. Not.

I’m haunted by the writer Maggie Black’s words here: “millions of people are expelled to the margins of fruitful existence in the name of someone else’s progress”.

That’s why my one of key points today is this: We are all emerging economies now.

CLEAN GROWTH?

The predicament of industrial civilization is that we have been striving after infinite growth in a world of finite resources.

A growing number of people, having realized that this is absurd, are now engaged an argument whether any kind of economic growth is consistent with sustainability.

In France, there are advocates of “decroissance” – “de-growth” – a radical change of course which its proponents compare to getting a drug addict off heroin. Advocates of degrowth propose to replace GDP with a “steady-state economy”, on the basis that any other course is a threat the planet and humanity.

Others say that while some aspects of today’s economy are dirty, not all of them are.

Carbon-based transportation and energy generation may be dirty, they say. but clean and waste-free production, or a focus on labour-intensive services, can surely expand the value of the economy without doing harm.

My problem with this latter version of ‘clean growth’ is that it still limits our understanding of the economy to the production of paid-for goods and services; it’s “GDP-light”.

For me, a better way to replace ecocidal GDP is to redefine what we mean by value, and wealth.

Rather than think of the economy as a machine for churning our merchandise, we should think of “economy” as the sum total of the ways we take care of so-called “current assets” – human, natural, and cultural assets.

Viewed through this lens, of valuing current assets, our economic focus shifts from perpetually increasing extraction and consumption – to preservation, stewardship, and restoration.

And do you know what? This is not complicated. The rules for a green economy are, following three decades of research and reflection, well understood.

Rather than strive to make the most profit, regardless of the consequences, a green economy:

1 sets out to meet human needs, whilst also protecting the capacity of natural systems to support life;

2 does not use natural resources faster than they can be replenished by the planet;

3 does not deposit wastes faster than they can be absorbed.

For high carbon, high entropy, highly complex societies, these rules are indeed hard to implement. But for an emerging economy like Sri Lanka, the jump is not so great. It’s more a matter of self-confidence than about re-tooling the whole economy, as is the case in the North.

The key to a new economy, in other words, is principally about a mindset – a clear ethical framework.

That ethical framework is easily stated: an unconditional respect for life, and for the conditions that support life: Acknowledging the biosphere as a systemic whole in which human beings are a co-dependent part.

Ethical statements along these lines crop up throughout the modern age. In 1949, for example, the American forester and ecologist Aldo Leopold proposed what he called a “land ethic” that would guide “man’s relation to land and to the animals and plants which grow upon it”.

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community” wrote Leopold. “It is wrong, when it tends otherwise”. [“Biotic community” here is another name for what we now call the biosphere].

Leopold argued that harm was frequently done to natural systems because of our culture’s belief in its separateness from, and dominion over, nature.

This myth of apartness dulls the sense of responsibility that would follow if we felt ourselves to be co-dependent members of natural community, he wrote.

This sense of apartness is not universal.

This myth of apartness is notably less pervasive in Sri Lanka.

ECO-TECHNICS

An ethic based on an unconditional respect for life, and for the conditions that support life, does not mean the abandonment of science or engineering.

On the contrary: it’s because of what science has taught us about the biosphere, and about the complexity and precariousness of nature — things that we did not know at the start of the modern age – that the time has come to re-define the ethical basis of the economy.

You may argue that this is to state the obvious: That of course your people respect life, and the conditions that support life.

But I stress the word unconditional. If a commitment is unconditional, it does not mean “take account of”; or “pay due respect to”; or “move steadily towards”.

It does not mean “minimise adverse effects on nature” – it means a target of *no* adverse effects.

Unconditional does not mean generating “less waste than any of our competitors” – it means a commitment to zero waste, and zero emissions.

All very fine and virtuous, you are probably thinking – but what’s to stop our competitors stating that they, too, have an unconditional support for life – only they then quietly cut corners and play games with the spirit and practice of ecological accounting?

When there are 40,000 lobbyists in Brussels alone – and probably double that number in Washington – what’s to stop the good guys losing out to the greenwashers?

ETHICS *AND* METRICS

A green economy has to be about ethics and metrics. It’s about clear moral purpose, backed up by rigorously defined and implemented measures.

At the technical level, new tools for ecological acccounting are coming along. Two years after the Stern Review, a report called The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), by Pavan Sukhdev, was published by Deutschebank and the European Commission.

Setting out a “comprehensive and compelling economic case for the conservation of biodiversity”, TEEB promotes a better understanding of the true economic value of the benefits we receive from nature.

According to TEEB, the global economy is losing more money from the disappearance of forests than through the banking crisis.

TEEB has the potential to be the trigger that transforms how business measures, and therefore looks after, these life-critical assets.

The Stern Review, and TEEB, provide new ways to measure the ecological impacts of economic activity on a large scale.

New tools are also nearly ready to help individual companies and communities measure the impact of their day-to-day operations on ecosystems. These tools, too, are in the pipeline.

In December last year, a report was published by Business for Social Responsibility called “Measuring Corporate Impact on Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Review of New Tools”. These developments mean that the true costs of long and complex supply chains can be measured.

Metrics and standards is, I know, a complex – and not always gripping – story. One of the biggest challenges is the sheer number of them.

Many people know about Fairtrade, which is about better prices, decent working conditions, local sustainability, and fair terms of trade for farmers and workers in the developing world.

But there are already close to 100 different labels addressing environmental or social sustainability, or consumers’ health, in the textile and clothing industry alone. The proliferation of labels and standards adds fog, not clarity, to the subject of ecological accounting.

One way to ensure that the good guys win – and the bad guy greenwashers have to toe the line – is to base the whole system, the whole fashion ecology, on principles of open-ness and transparency.

I know this runs against the deepest habits of the fashion industry, but in an open system, the liars will be found out.

A second way to ensure the good guys win is to find certification partners who are above reproach. Just as an example, I’m tremendously impressed by the work of Christian Aid in mapping the global impacts of supply webs.

It was Christian Aid who demonstrated that the UK, which had been boasting that it was only responsible for two percent of global emissions, was in fact responsible for 12-15 percent of global emissions once their ownership of production in China and India was factored in.

So yes, we need metrics to police our impact on the natural world. But what about the people side of sustainability?

In Europe and the US – in the “advanced” economies – there’s a tendency to equate “green jobs” with such occupations as the installation of solar panels, or erecting wind turbines.

There’s an assumption that a knowledge-based and creative economy necessarily entails more high tech, is more complex, and involves a higher monetary throughout.

But for me a green economy is not about replacing one set of production-line jobs with another – only in a green building, and framed by ethical terms and conditions.

We have all been impressed by the extraordinary achievements made here in Sri Lanka on both these counts. But I hope you will take is as a mark of respect if I make the suggestion that you can do even more.

For a green economy needs to be be about livelihoods, not just jobs.

The concept of livelihood embraces all the resources and activities – material, social, natural – required for a means of living. All of life, not just nine-to-five life.

Jobs invariably involve money. Livelihoods, being the property of a community, may or may not involve money.

For example, artisan communities contain vast amounts of knowledge. In India, for example, there are up to 15 million people for whom artisanship, and livelihood are as one. What they know about working with nature, and its materials, in a place, are the means by which they are able to do their work.

There are at least as many artisans in South Asia as there are creative professionals in Europe. Probably many more. Your artisans did not go to design schools, and their knowledge cannot be expressed in words, numbers and rules.

But for me, their tacit, contextual knowledge is at least as valuable and important as knowledge owned by the “creative class”.

As my friend Jogi Panghaal has taught me over 20 years, we all have so much to learn from artisans about their habitats, their food and drink practices, dance forms, healing traditions, their stories, songs, theatre, and dance, dress and traditions.

Jogi likes to say that “you make with material, but the material makes you”.

A skilled artisan knows more about economy of means than 100 value engineering consultants. One local farmer is more important to food security than a laboratory full of genetic engineers.

This is not to be sentimental about artisans.We northerners too often make assumptions about people who do what they do, and live in particular ways, in response to specific conditions.

It’s insulting of us to demand of ethnic or indigenous communities that stay as they are, and don’t change, just because we find their ways of life quaint – and marketable back in the North.

Sometimes traditional ways are optimal; sometimes a fusion of old and new will be better. But it’s not for outside experts to make that call. There need to be continuous discussions, between all actors in the fashion ecology, about what are appropriate and sustainable types, tempos and scales of production.

Designers have an important contribution to make – but not as the bringers of product bluepints and price points.

Designers can cast fresh and respectful eyes on a situation to reveal material and cultural qualities that might not be obvious to those who live them.

I hope I have made it clear by now that the green economy is not being made by clever guys staring at computer screens in shiny buildings, protected by guards.

No: the green economy is being made wherever people are growing food in cities. The green economy is where people are opening seed banks. It’s being made where communities are removing dams, and restoring watersheds.

Anywhere you find car-share schemes, or off-grid energy – there is a green economy hotspot.

You’ll find the green economy wherever people are launching local currencies. Non-money trading models are cropping up like crazy: nine thousand examples at last count. In their version of a green economy, 70 million Africans exchange airtime – not cash.

Thousands of groups, thousands of experiments. For every daily life support system that is unsustainable now – food, health, shelter, and clothing -– alternatives are being innovated.

The keyword here is *social* innovation.

Social innovation is all around us. Every community contains assets in the form of people and their skills and their culture. By some accounts, there are one million grassroots environmental organisations out there in the world; the website Wiser Earth, alone, lists 120,000 of them.

Examples in the North have names like “Post-Carbon Cities” or “Transition Towns”.

The Transition Towns movement, especially, is highly significant if you want evidence, here in Sri Lanka, that things are changing, and profoundly, in the North.

Transition initiatives, which only started a couple of years ago, are multiplying at extraordinary speed. More than 200 communities in Europe and North America have been officially designated Transition Towns, or cities, districts, villages – and even a forest.

A further 2,000 communities around the world are “mulling it over” as they consider the possibility of starting their own Transition Initiative.

The transition model – I’m quoting their website – “emboldens communities to look peak oil and climate change squarely in the eye”. But they don’t just look: Transition groups break down the scary, too-hard-to-change big picture into bite-sized chunks.

The essence of their idea is to create a disaster response preparedness plan just in case the calamaties of peak oil, and economic or environmental collapse, actually happen.

Transition Towns practise risk management and due diligence – but in a social context.

Transitioners, as they call themselves, develop practical to-do lists; they put those items in an agreed order of priority and then start to work on the priority tasks they’ve agreed on.

Their focus is the notion of resilience. “Fui so” in Chinese: the capacity of a system to adapt to change, to rejuvenate.

Resilience means the capacity of a place-based community to survive without the profligate energy and resource consumption that the advanced economies have become used to.

The Transition model is powerful because it brings people together from a single geographical area. These people, of course, have different interests, agendas and capabilities. But they are united in being dependent on, and committed to, the context in which they live.

Just like the artisan communities I talked about a bit earlier.

A second reason the Transition model is so powerful is that it uses a process of setting agendas and priorities – the “open space” method – that is genuinely inclusive of all points of view.

I do not suggest that Transition Towns is a model you need to adapt for Sri Lanka. On the contrary, you have fascinating experiments here.

We were impressed by direction being taken by the Slow Food movement here for example, and fascinated by the business model for sustainable food, agro-forestry and rural development of a private entity, Saaraketha.

I hear that your home-grown Sarvodaya movement, active in 15,000 villages here, shares many of the Transition Towns interests: self-reliance; community participation; micro-credit; an holistic understanding of communities and natural systems. And Sarvodaya has been growing and adapting for nigh on 50 years.

There are elements of Buddhist or Ghandian thought in Transition thinking, too. But it is inevitable, and right, that responses to the great transformation we are all involved in will take different forms in different contexts.

STEPS

For the last part of my talk I promised you some practical suggestions about how to proceed from here on in the fashion industry – especially when the buyer has so much power, and when the interests and cultures of so many stakeholders need to be aligned.

I borrowed a phrase from the theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe this stage of our journey: “the Dance of the Big and the Small”.

It is true, of course, that who holds the purse, has enormous power. But she or he is not omnipotent.

On the contrary: the most important feature of the green economy I have described today is co-dependency – of man and nature, developed and under developed, of artisan and fashion system.

As I said at the start, I sense, everywhere I go, that awareness of co-dependency is being rediscovered at astonishing speed. Untold millions are waking up to the fact we are not separate from and above the biosphere. We live and act inside a complex of inter-connected systems.

As that realisation sinks in, we are realizing that our journey is not heading for a single place, like Xanadu.

Our destination is not a thing, like a Holy Grail.

Sustainability, or resilience, is not a secret code that will be revealed, with great fanfare, when we complete a trying pilgrimage.

Nobody knows how the green economy will look or work in detail. I don’t. You don’t. Sir Stuart Rose from M&S doesn’t know.

No: a green economy is about ways of perceiving, and ways of acting in the world that we will discover together.

We have heard a lot about the buyers for huge brands whose only interest seems to be to drive down prices. We’ve heard how fast-fashion seems to be accelerating of its own accord, with more and new products launched at ever shorter intervals. We’ve heard that young people seem to be unconcerned by big picture issues, and drive this manic consumption along.

The answer is not to try and confront this rampaging beast head-on.

The answer is to create experimental lines and channels on the edge of your main business. Give people access to experiences – and some products – that are unexpected, different, and authentic. And see what happens.

I learned this week about a special problem in the regard: if you launch a line of “ethical” products, they make all your other products look, by implication, un-ethical! So create a parallel brand, like the airlines did when threatened by the low-cost carrriers.

One of your industry leaders told me of his pride that Sri Lanka has evolved from a “nation of tailors” to a “master of integrated solutions”.

To be honest, this does not sound to me like progress. I respond more warmly to the idea of a tailor than to an “integrated solution”.

Please look after and nurture your tailoring traditions – but look for new ways to make them viable as a business. Connect the people who make things, here, with people in other places who need clothes and would dearly love to have a direct relationship with the person who makes them.

The true fashion innovator will bring new and different actors together on modest experiments of the kind I just described.

The most important innovation tool will be a question, not a product specification: “how might we connect our tailor-makers to individual customers in a way that delivers value to all the parties involved fairly, and sustainably?”

There’s always a danger, in talking about ethics, as I have done here today, that one ends up sounding like a priest telling people what to believe, and how to behave.

I know the fashion industry well enough to know that this would be a futile way to act.

I prefer to be thought of as a bee, than a priest. Bees cross-pollinate between plants – and don’t forget: without the bee’s visits, there would be no life.

There are many individuals out there – the odd ones out, the people who don’t fit neatly into a box, or into a budget heading. They are often the bees among us.

But I also talked about the Dance between the Big and the Small. Maybe what we need is a new kind of dance master to teach all the different actors new steps, and how to work together.

It would be fun to explore that idea but – perhaps just as well – my time is up.