Its publisher, Bloomsbury, describes designing designing as “one of the most extraordinary books on design ever written”. It’s therefore welcome news that – after a period out of print – this classic book has now been reissued. (That’s my copy in the photograph above; it just arrived). The following text is included as an afterword. It was written by me to celebrate jones’s The Internet and Everyone in 2000, and was then republished on the occasion of his 90th birthday.

I’ve been rereading The Internet and Everyone by john chris jones.

I’ve been astonished once again by the sensibility of an artist-writer- designer whose philosophy – indeed his whole life – first inspired me when I was a young magazine editor more than thirty years ago. Like another muse of mine, Ivan Illich, John Chris Jones was decades ahead of his time. The time is ripe now for a wider readership.

He wrote about cities without traffic signals in the 1950s – sixty years before today’s avant-garde urban design experiments.

In the 1960s, Jones was an advocate of what today is called ‘design thinking’; (then, it was called design methods).

He advocated user-centered design well before the term was widely used.

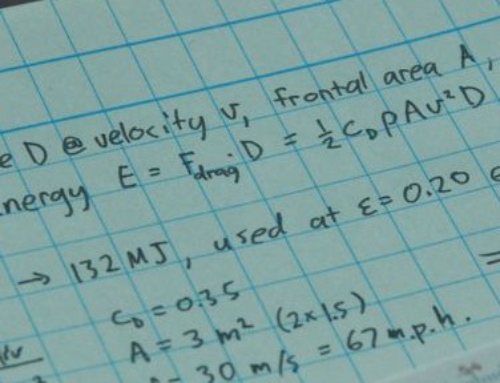

He began by designing aeroplanes – but soon felt compelled to make industrial products more human. This quest fueled his search for design processes that would shape, rather than serve, industrial systems.

As a kind of industrial gamekeeper turned poacher, Jones went on to warn about the potential dangers of the digital revolution unleashed by Claude Shannon.

Computers were so damned good at the manipulation of symbols, he cautioned, that there would be immense pressure on scientists to reduce all human knowledge and experience to abstract form.

Technology-driven innovation, Jones foresaw, would undervalue the knowledge and experience that human beings have by virtue of having bodies, interacting with the physical world, and being trained into a culture.

Jones coined the word ‘softecnica’ to describe ‘a coming of live objects, a new presence in the world’. He was among the first to anticipate that software, and so-called intelligent objects, were not just neutral tools. They would compel us to adapt continuously to fit new ways of living.

In time Jones turned away from the search for systematic design methods. He realized that academic attempts to systematize design led, in practice, to the separation of reason from intuition and failed to embody experience in the design process.

After watching the rapid wing movements of a flying duck, Jones compared ‘the beautiful, unconscious and ever-changing complexity of natural control systems with the stiffness and self-conscious centrality of all forms of government, management or social control’.

Jones called for the re-introduction of personal judgement, imagination and aesthetic sensibility into the design process.

He came to believe in ‘reversing the reversal’ – by which he means the Renaissance ‘and its antecedents in ancient Greece and at the end of Stone Age thinking when masculine gods and values displaced feminine ones, and notions of domi- nance replaced those of receptiveness’.

The Internet and Everyone is the opposite of a how-to textbook. But at one point, in a passage on contextual design, Jones lightly introduces a manifesto that calls on designers:

To begin with what can be imagined

To use both intuition and reason

To work it out in context

To model the contextual effects of what is imagined

To change the process to suit what is happening

To refuse what diminishes

To seek inspiration in what is

To choose what depends on everyone.

A character in the book (who I ‘think’ is Jones) attributes this sensibility to being brought up in an old culture – in Wales – where ‘the renaissance never happened’ and ‘pre-Cartesian thinking is in the language’.

John Chris Jones’s real enthusiasm, throughout the years, has been for a kind of social designing that did not even have a name when he started writing and teaching about the subject.

He decided that he would not try and change the system from within.

So, thirty-six years ago, Jones resigned from institutional life – from having a job, material security and a neat job label – for the life and economy of an independent writer, researcher and artist.

Since then Jones has written ‘design plays’ and other fictions, many of which are included in The Internet and Everyone.

‘I’ve been drawn to study ancient myths and traditional theatres for decades,’ he writes. ‘Unless we can rid modern culture of its realisms there is no getting out of the grim realities of commercial engineering and the way of life built on it.’

With its multiple voices and formats, this is not a book that I would presume to ‘review’ in a linear way. The best I can do is tell you how much I have been inspired by its 560 pages and urge you to explore the book for yourselves.

Jones writes, ‘There are two kinds of purposes. The purpose of having a result, something that exists after the process is stopped, and does not exist until it has stopped … and there is the purpose of carrying on, of keeping the process going, just as one may breathe so as to continue breathing. The purpose is to carry on.’

Long may John Chris Jones carry on. Here is his public writing site.