In 1996, when Ivan Illich agreed to speak at Doors of Perception in Amsterdam, our theme that year was ‘speed’. The philosopher surprised us by bringing along two fellow speakers: Sebastian Trapp, a field biologist, and Matthias Rieger, a musicologist. Their contributions are as fresh today as twhen we heard them in Amsterdam – so we are running them again in three parts. This the second.

Matthias Rieger: Some remarks about speed from a belly-dance drummer’s point of view

When I prepared for this conference about speed, I was somewhat at a loss what to say in front of people who would have come from all over the world by car, train, or plane. This event, so I read in the programme, should give scientists, designers and philosophers a chance ‘to rub their brains’. After a while, I decided to ask my drum teacher Mohammed for help.

He is a good friend of mine and a experienced musician. For two years now, he has worked hard to introduce me to the art of belly-dance drumming. After the weekly drum lesson, I told him that I was invited by the Netherlands Design Institute to speak about speed in music. I planned to talk there about the introduction of the concept of speed into society.

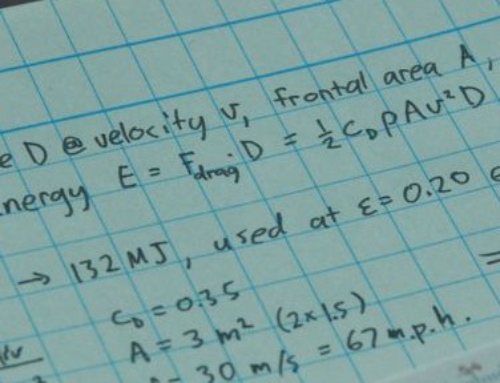

I wanted to use the example of the metronome to demonstrate how speed came into music. This device was invented in 1812 by the Dutch technician who lived in Amsterdam, maybe just around the corner from the place where I speak now. His idea for the little machine, designed to give the right speed for the performance of music, was stolen by a German technician, Nepomuk Maelzel, who patented Winkler’s idea in Paris and London, and commercialised it in 1816. The metronome is a technical device that sounds a regular beat at adjustable speeds dictating to the musician the beat he has to follow. The mechanism is based on the principle of the double pendulum, i.e. an oscillating rod with a weight at each end, the upper weight being movable along a scale. A clockwork maintains the motion of the rod and provides the ticking sound every beginner in music knows so well. By adjusting the movable weight along the rod, the pendulum swings, and the ticking can be made slower or faster. An indication in a musical score that some note-value is to be performed at MM (Maelzel’s Metronome) = 80, for example, means that the pendulum oscillates from one side to the other (and ticks) eighty times per minute, and the note-value specified with the indication should be performed at the rate of eighty per minute.

Very interesting, Mohammed said. But, what do you think speed could mean in music? What do those people want to talk about? Well, I said, if I have understood them right, they want to figure out how one can reduce speed in society by creating new designs for a slower society. I guess that means something like reducing speed on highways from 120 to 90 kilometers per hour, or music, from 98 beats per minute to 60. I explained to Mohammed that I would try to illustrate the introduction of speed by the example of a discussion in the field of musicology dealing with so- called historical performance practice. This controversy started at the beginning of this century with a renaissance of baroque and classical music. Since then, opinions clash about the interpretation and use of the metronome indications given by the composer. One side in this controversy argues that classical music today is performed too fast. They maintain that this occurs because of the general acceleration of all aspects of modern life since the invention of the railroad. They suggest cutting the indications of the scores by half, from 120 to 60 beats per minute, for example. Let me call them ‘slobbies’, taking a cue from economists who have created the term for ‘slower but better performing people’. Those on the other side insist on performing the music in exactly the tempo indicated in the score; this is the only way to get the ‘original’ sound.

Ah, Mohammed interrupted me, I understand: Porsche and Beetle drivers reflecting on music. One of the first composers who gave metronome indications was Ludwig van Beethoven. He was a friend of Maelzel and supported the introduction of the metronome in Germany. But Beethoven was utterly shocked when he listened to the first performances of his music, following his metronome indications. MM did not work. He decided to change them several times. Finally, he came to the conclusion that the use of measured tempo makes no sense in music, and he was not the only composer to do so. But, I asked, didn’t we both use a metronome for my first belly-dance drumming performance? It seemed the best way for me to get the exact speed for the dancer. Well, Mohammed replied, at that time you had almost no experience with belly-dancing. Otherwise you would never have agreed to follow a technical device instead of your own certainty of the right, the appropriate, the good way to perform. This certainty arises out of the interaction between the experience of the dancer and your own.

As you can imagine, I was disturbed by Mohammed’s remarks. I decided not only to continue my two hours of daily practice but I also wanted to figure out how in the history of western music musicians found the right tempo for their performances.

One week later I called Mohammed and invited him for a cup of tea in order to continue our conversation. He was delighted and promised to come with a friend. Her name was Abla. She was a belly-dancer who had worked with Mohammed for a long time. After they arrived I prepared some good tea, served some sweets and we began to chat. Well, Mohammed, you really set me thinking with your remarks on the metronome and music. I looked into the history of western music because I wanted to figure out how musicians in the past thought about musical tempo. You can hardly imagine my surprise when I found out that until the nineteenth century the musical tempo was always determined by the setting: a special event, a place, a type of work or action. For example, work songs are related to the rhythm of work, the tempo of dance music to the acoustics of the place and, of course, to the mood of the dancers and musicians.

The need for some kind of indication of tempo began to be felt only at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Composers started to use Italian time-words like adagio (‘at ease’), allegro (‘cheerful’) or presto (‘quick’). However, these time-words did not refer to a measured time that could be expressed by units per minute. They were at once indications of the mood and spirit or character of the piece. Carl Philip Emanuel Bach wrote in the middle of the eighteenth century in his Versuch, ber die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen: ‘The tempo of a piece, which is usually indicated by a variety of familiar Italian terms, is derived from its general mood together with the fastest notes and passages which it includes. Proper attention to these considerations will prevent an Allegro from being hurried and an Adagio from being dragged.’

I then took a look at the writings on dance and, there again, I found that it simply does not make sense to compare the tempi of different kinds of dance. A sarabande is not faster or slower than a minuet or a waltz. It is simply a sarabande and you should perform it as a sarabande has to be performed. They all have their own character and you cannot simply reduce this to an indicated mechanical time.

The first machine to measure musical tempo was invented in 1698, long after the first pendulum clock had been built in France. This machine, called ‘Chronomètre’, was invented by the French music theorist Etienne Loulie, and was still famous in the eighteenth century. It was very expensive and almost two metres high, and was only used by few musicians, but mainly music theorists and scientists. Even after Winkler had invented his much smaller and easier to handle version, the metronome was not important for most musicians. It was only later, with the commercialisation of the metronome by Maelzel and the support of famous composers like Beethoven, that the metronome became the instrument for measuring musical tempo.

Although the metronome became common at the beginning of the early nineteenth century, other non-technical ways were found to hint at the right tempo. One was the use of the musician’s pulse as a measure. This method was mentioned first in the sixteenth century by an Italian monk named Zaccini, who gave a brief description of measuring time with the pulse in his Prattica di Musica. The then famous flautist Johann Joachim Quantz wrote in his Versuch einer Anleitung die Flöte traverse zu spielen the following marvelous sentences: ‘One would like to make certain of this: take as a basis the pulse of a cheerful and healthy person of hot-tempered and careless disposition or, if one may be permitted to say so, of a person with a choleric temperament, after lunch, towards evening. Then one will have selected the correct one. A depressed, sad, or cold-blooded and sluggish person might take the tempo of every piece somewhat more briskly than his pulsation.’

But all these methods of measuring tempo were mostly used by music pupils or dilettantes, people who had little experience, like young belly-dance drummers today. These were crutches to get an idea of the appropriate tempo. Quantz, who described the method of pulse measurement, also wrote: ‘If one has practiced this for some time, then gradually the mind will become so familiar with the tempi that it will not be necessary to consult the pulse.’ And Leopold Mozart, at this very same time, went even a step further. For him, knowing the appropriate tempo from one’s experience, not by using a technical device, was the main qualification for being a musician.

This is very interesting, Mohammed said to me with a sly smile. Come on, pick up your drum and let’s try to reflect on the concept of speed with the help of Abla. Just play a simple rhythm. Abla will dance with you. See if you can get the right tempo with the help of the metronome. So I adjusted the metronome at 60 minims per minute and started to play. I immediately recognized that something was wrong. Abla moved, but not at ease. She really had difficulties following my drumming. Drum and dancer did not harmonise. Stop, Mohammed shouted, you are wrong. Yes I know, I said — it seemed to me that Abla had started to hate me. Shall I play slower or faster? No, Mohammed replied, you should not play faster or slower, you should play right. But I played exactly 60 minims, I answered. I know, Mohammed said. Following the machine is the best way to play with exactness, which also means to be always wrong. There cannot be a fit between you and Abla, as long as you look at her from the machine’s point of view. If I have understood you right, Matthias, this is exactly what the people at the conference in Amsterdam have in mind when they reflect on speed in society. Try it again without the metronome and just concentrate on Abla. So I took my drum again and started to play. It was not easy, but after a time and with the help of Abla I found the right groove, the appropriate tempo. It fitted. I think I got it, I said to Mohammed with some pride in my voice. Yeah, he said, if you continue to practice very hard for ten or twelve years, you might really make it.

It was getting late and Abla and Mohammed had to go. Mohammed, I said, I still have to speak to those people in Amsterdam. Well, he replied, try to look at it from a belly-dance drummer’s point of view.

Copyright: Sebastian Trapp, Matthias Rieger, Ivan Illich

For further information please contact:

Silja Samerski Albrechtstr.19 D – 28203 Bremen

Tel: +49-(0)421-7947546 e-mail: piano@uni-bremen.de