I was honoured by the invitation to write this Foreword to El ABC del Diseño de Emiliano Godoy During a 30 year career (so far) of learning-by-designing-and-making, Godoy has discovered other reasons to produce than just feeding the economy.

toronjaediciones.com/el-abc-del-diseo-de-emiliano-godoy

On a recent visit to the the Highlands of Scotland, a cab driver pointed proudly to a group of timber-framed private houses, clustered next to a forest. “You’re looking at the future of construction” my driver told me proudly.; “those timber frame kits use 100 percent Scottish timber and are being used by home developers right across the UK”. The website of a leading timber frame company accentuated this positive message. “Timber frame is the most sustainable and technologically advanced form of construction. A quicker build time translates into quicker returns and improved financial performance for your business”.

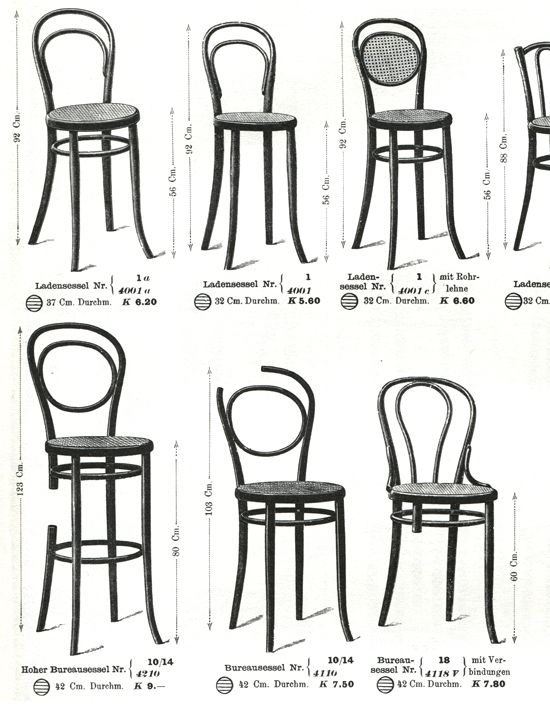

The growing success of Scottish timber-framed buildings should have felt like good news. Instead, I was reminded of Emiliano Godoy’s project Depleted Thonet (which Andrea Chin wrote about in Designboom). Godoy discovered that Thonet, the first maker of affordable mass-produced chairs, had been forced to move production frequently as its production depleted the forests where its factories stood. Until then, I’d regarded Thonet as a byword for light, responsible, and affordable design. This memory triggered an unsettling thought in Scotland: could timber-framed buildings end up depleting forests again as their own sales soared? In Depleted Thonet, Emiliano Godoy riffs on an intriguing question: what if Thonet had stayed in the same place during its early years, instead of moving to new locations every time they ran out of resources? On three posters, Godoy erases portions of products in a Thonet catalogue as an analogue of the forests the company erased during its early years. But, trapped within an extractive mindset, the company could not contemplate any limits to production. It either stopped thinking about rivers, soils, and biodiversity at all – or treated them as resources whose only purpose was to feed ‘the economy.’

This much we know: Today’s perpetual growth economy cannot be reconciled with the the biophysical limits of a living planet. That’s why the ongoing search for new forms of production on their own – whether ‘clean’, ‘green’ or ‘circular’ production– is not taking us in the right direction. A circular economy, for example, is about making production more efficient – but its underlying objective remains unchanged: produce, produce, produce. The late Bruno Latour described our predicament with clarity:. “This idea of framing everything in terms of the economy is a new thing in human history. We don’t just need to modify the system of production, but get out of it altogether”.

Whether it was chairs 150 years ago, or timber-framed houses today, the challenge remains the same: how might design transcend an economic system that consumes nature in order to grow? In our efforts to find an alternative way. So far include myriad projects, manifestos, systems, and organizations that have told us, over decades, how to do better – but concludes that they were, and remain, ineffective. For every sustainable, green, circular, or ecological project we have tried, there have been hundreds of projects that at best preserve the status quo, and at worst push us towards even more polluting systems. The good examples, ultimately, are excellent exceptions.

In the case of Emiliano Godoy, he is a realist, but he is not a defeatest. During a 30 year career of learning-by-designing-and making, he discovers other reasons to produce than just feeding the economy. He writes movingly, for example, of designing a shelter for a community of deported people in Tijuana. A roof for shelter, and a space of solidarity, are significant objectives in themselves, of course, and once in place, the pavilion becomes a hub for the community to gather, connect, and support each other. But the project’s purpose was not just practical: by fostering new relationships, it changed the city’s perception of a marginalised community – and the community’s perception of itself. At one point, an elderly individual approaches the pavilion, and asks, “is this the place where one is heard?.”

Meeting the need to be heard, to be seen, and to be respected, is a powerful mission for the design journey ahead – and not just for humans. Our purpose, now, is to design for all of life, not just human life. This ecological approach to design recognises the inextricable links between humans and their biophysical, social, and economic environments. As you will discover in the pages that follow, this kind of design is about caring relationships – between people, and with place. Production is a means to this destination, not its. purpose

Connecting with nature in design – designing for life – involves a lot of learning, and a lot of time. Personally, I am comforted by a comparison of our own age with that of Copernicus, half a millenium ago. When the great mathematician and polymath proved that the earth revolves around the sun, rather than vice versa, it took a further 100 years of argument and resistance before the consequences of his discovery sunk in. The same lesson applies to all of us in design today: On such a fundamental issue as our place within nature, learning to think and feel our way into an ecological world view is a lifelong journey.