As an artefact, the swallows’ nest is not exactly the Taj Mahal. It’s a ramshackle structure, made of mud pellets and straw, that’s stuck crookedly to the wall. But it seems to suit them well – or rather, the surrounding habitat does.

I’m sad. The family of swallows that spent the summer in the eaves behind my office have headed south for the winter. Most of them will follow the west coast of Africa to avoid the Sahara; a few may travel further east down the Nile Valley. They’ll take it easy and stop every few miles at first to build up their fat reserves – but then they’ll speed up. In four months, as Christmas beckons here in the north, they’ll reach their destinations: Botswana, Namibia or South Africa. After just two months gorging on insects, they’ll begin the epic journey back. The strongest among them will make it back in just five weeks, traveling 200 miles a day.

And I thought my air travel was profligate.

As an artefact, the swallows’ nest is not exactly the Taj Mahal. It’s a ramshackle structure, made of mud pellets and straw, that’s stuck crookedly to the wall. But it seems to suit them well – or rather, the surrounding habitat does. Their physical abode is a safe place to park their ravenous young – but it’s not a gated community. What brings the swallows back every year is the environment as whole: open air for easy flight; fresh water from the river; flying insects to feed themselves and their ravenous young.

When the swallows twitter excitedly overhead, I envy how lightly they manage to live. I compare their tiny needs for external energy to the prodigious amounts needed to keep us humanoids fed and watered. I contrast the way the swallows throw their nests together – from found materials – with the billions of tons of resources, often gathered from faraway lands, that we pour into our own structures. And which we basically sit in, waiting to be provisioned.

For ninety nine percent of human existence we lived far more like the swifts than we do today. We had very few possessions. Materials for shelter, clothing, and tools were all at hand. Because we needed little, we wanted little. We got by without a state, a market, or advanced technology. We thrived in the absence of strategic visions, design thinking, concepts, plans, budgets, or controls. We worked, for the most part, cooperatively. We didn’t borrow from the future. We shared.

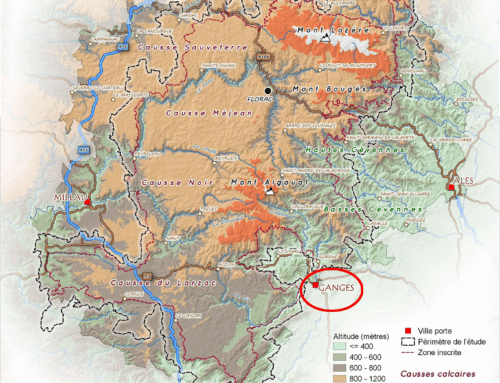

[Above: the flyways of migratory birds. Source Wetlands International]

When my birds lined up on the telephone wires, nobody had told them to do so: They were responding to subtle changes in the light, and in the taste of the air, that I will never know.

I’m more than a little envious – but it’s time for work: I have to pack for a trip.

POSTSCRIPT

I’m happy again: a few minutes after I finished the post above these 300 sheep – each with its own bell, and accompanied by five shepherds and six dogs – strolled into town along our “dry” river: le Rieutord. They are on Day 4 of the transhumance – their annual pilgrimage from summer pastures to winter quarters. The chief shepherd has been making this journey for 32 years at the same steady pace; similar groups have being doing the same for thousands of years. Modern mobility is – well, just not the same.

.