I wrote the following text for a new book, Human Cities: Challenging The City Scale (published by Cite du Design and Clear Village).

The Greek physician Hippocrates described the effects of “airs, waters, and places” on the health of individuals and communities. For a short period, the industrial age distracted us from this whole-systems understanding of the world – but we are now learning again to think of cities as habitats, and as ecosystems, that co-exist on a single living planet.

Humanising the city in this context – making it healthy for people – therefore means making it habitable for all of life, not just human life. It means thinking of the city as a local living economy, not as a machine. And it means the embrace of biodiversity, and local economic activity, as better measures of a city’s health than the amount of money that flows through it.

The notion of the city as a living system generates cultural energy, too: A narrative based on caring – for each other, and for our places – creates the meaning and shared purpose we’ve been so badly lacking.

Civic Ecology

One design consequence of this cultural awakening is the growth of ecological urbanism, or civic ecology. These practices study how to help living organisms and their environment thrive together. They enrich city design with the insights of ecology, botany, climatology, hydrology, geology, and geography.

This movement is growing rapidly: The Urban Nature Atlas, for example, contains more than one thousand examples of nature-based solutions from across 100 European cities. And another fast-growing platform, The Nature of Cities, hosts 650 professional contributors from around the world.

Ecological urbanism is not much about planting seeds on barren ground. On the contrary, it builds on some surprisingly good news. Scientists are finding that there can be more biodiversity in cities than in many rural areas that we think about as ‘nature’. Urban biologist Claudia Biemans, an edible plants researcher in The Hague, identified about 300 different species in one square km of her city compared to 50 different species found in the same area of industrially-farmed countryside nearby.

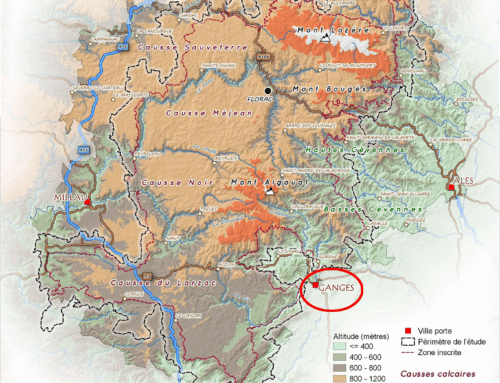

An ecological approach preoccupied by the the concepts of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ is becoming redundant. A better approach to city design involves care for living systems that already exist at a bioregional scale, but have been neglected or ignored: watersheds, foodsheds, fibersheds and food systems.

Urban food projects are good examples of social innovation, and civic ecology, converging. Twenty years ago urban farming projects were small and disconnected – but they are now becoming pervasive thanks supporting social infrastructures: Educational and leadership programs, job training for underserved young people, internships, and hands-on workshops. By 2017 the city of Milwaukee boasted more than 100 urban farms. As pioneer Will Allen puts it, “we’re not just growing food, we’re growing community”.

Locality

A growing body of research confirms that small-scale, locally owned food businesses create communities that are more prosperous, entrepreneurial – and, yes, connected – across a wide range of metrics.

The beauty of local-ness as a measure of value is that it generates a practical to-do list in the form of new enterprises, new economies, and new livelihoods, that need to be created.

A variety of local economy blueprint tools are now available to help citizens and city managers begin this work: Tools to measure the percentage of food grown locally; the amount of local currency in circulation as a percentage of total money in circulation; the number of businesses locally owned; the percentage of energy produced locally; the quantity of renewable building materials available; the proportion of essential goods being manufactured within the community.

The convergence of civic ecology and local economic development is not just a task for scientists and policy makers. A variety of different stakeholders – formal and informal, big and small – need to to work together. The question – and it is also a design question – is how?

One precondition for working together is to curate meaningful conversations among all the people who need to be involved. An especially effective approach has been developed in England by Encounters Arts. Their Art of Invitation practice uses techniques from theatre, as well as the insights of psychology, to bring people together who are diverse in age, experience and background. The group’s facilitators – many of them artists – have developed groundbreaking approaches to the to the co-creation of a shared response to systemic challenges facing their communities.

Co-operation

Once local-scale conversations are under way, the next challenge is to organise real-world activities in an equitable way.

A good candidate for this task are so-called Platform Co-ops. These platforms enable multiple actors – including businesses, government institutions & NGOs – to meet basic needs collaboratively: shelter, transportation, food, mobility, water, and elder care. Value, in a platform coop, is shared fairly among the people who make them valuable. Its activities depend more on social energy, and trust, than on fixed assets and real estate. There’s an emphasis on collaboration and sharing; on person-to-person interactions; on the adaptation and re-use of discarded materials and abandoned buildings and land. Thriving neighbourhoods also need shared community spaces.

In London, the Participatory City Foundation is s breathing life into communities by helping citizens develop shared gardens, canteens, kitchens, workshops, and maker spaces.

If humanising the city is mainly about life-friendly and resource-light ways to meet daily life needs, then the poor people of the world are further down the learning curve than the rest of us.

The diverse ways in which poor people meet daily life needs are usually described as poverty, or a lack of development – but in 35 years as a guest in what used to be called the ‘developing’ world, this writer has come to a startling conclusion: Living sustainably is second nature for people who cannot depend on the high entropy support systems of the industrial world.

Humanising the city must surely include connecting with the shadow economy of poor people and their diverse cultures.

This is not to trivialise the extreme challenges faced by poor people on a daily basis – but the fortunate among us have much to learn from the ways people with low cash incomes meet these needs in an ad hoc way. Other cultures than our own have developed sophisticated ways to mutualise risk among traditional networks of reciprocity and gifts; many social systems based on kinship, sharing, and myriad ways to share resources already flourish outside the formal economy.

Commoning

Millions of local living economies already exist wherever people are meeting practical needs using local resources. But a lot of this work feels fragmented. We’ need an umbrella concept, a coordinating idea, to make sense of the work we do as individuals in the swarm.

The Commons is that umbrella concept. As an idea, and a practice, it generates meaning and hope. Commoning gives shared meaning to the emerging ‘leave things better’ politics that otherwise lacks a name. It’s the opposite of the drive to turn everything into money.

Seen through that lens, the commons provides a motive for all a city’s inhabitants to care collectively for the living systems of a city: land, watersheds, and biodiversity, for sure; public buildings and spaces, of course; but also social systems such as common knowledge, software, sharing platforms, or skills.

The important thing is that the commons are a form of wealth that a community looks after, through the generations. The idea embodies a commitment to ‘leave things better’ rather than extract value from them as quickly as possible. And because the commons, as an idea, affirms our codependency with living systems and the biosphere, it also represents the new politics we’ve all been looking for to replace the industrial growth economy we have now. The commons is a system by which a community agrees to manage resources, equitably and sustainably – as we have done for most of human history.

end