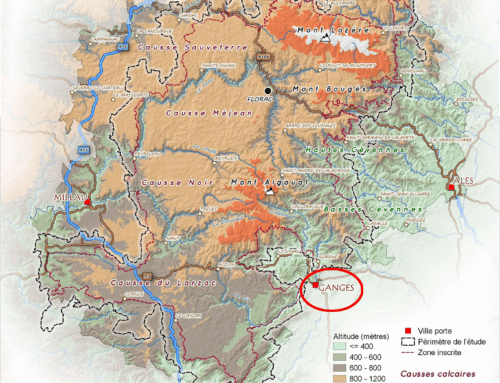

It was generous of the The Building Information Centre (YEM) and 34Solo to host an xskool event in their city last week. Our starting premise, after all, was that Turkey’s 30 year long construction boom is losing momentum. True, the sound of jackhammers was pervasive in Istanbul during our visit – but the cold winds of the global crisis are making themselves felt. An estimated 600,000 dwellings stand unsold in the city and, in January, a first attempt to raise private funding for a third bridge across the Bosphorous failed. Not a single company showed interest.

Back in 1995, Mayor Erdogan of Istanbul declared that a third bridge would be “murder” for forests and reservoirs around the city. Irreplacable green areas and wetlands, of unique ecological importance, would be destroyed by the bridge, its associated roads, and subsequent development. Despite knowing this, the national government in Ankara – now led by Prime Minister Erdogan – has revamped the bridge project in an attempt to lure contractors and investors back. It is now offering participants in the project a “guarantee of heavy traffic” across the bioregion the bridge would reach.

What drives this ecocidal policy? According to Haluk Gercek, a professor of transport planning at Istanbul Technical University (speaking to The New York Times), the bridge “has nothing to do with solving the traffic problem and everything to do with developing property,” Otherwise stated: Turkey’s Real Estate Industrial Complex – like the ones in China, Spain, and the US – has grown too big to be allowed to fail. Banks, private developers, and construction companies must expand their activities to infinity – or watch their market collapse.

Trouble is, just because a property bubble is Too Big To Fail does not mean it will not fail. If the jackhammers do fall silent, what would happen to Istanbul then?

A next economy: already here

This is where xskool comes in – as a kind of social seed exchange of the next economy. Rather than dream up exotic visions of “what could be”, an xskool looks for social and natural assets that already exist – and grows from there. We bring together projects, however modest in scale, that meet daily life needs using the low-energy processes of natural systems, combined with the metabolic energy of social innovation.

In her book Life Rules, Ellen LaConte describes they ways that “nature unfolds the future from what is here now”. This was our approach in Istanbul. Working with the collective who organise the Sustainable Living Film Festival, we invited a variety of projects to participate. Only some of these projects were fully-formed, and all were small. Our idea, rather, was to say: “behold: green shoots! how can we help each other flourish?”.

It was encouraging to discover just how many many intriguing social lifeforms flourish across Istanbul already. A variety of informal systems has been developed by newly arriving immigrants to meet their need for housing (gecekondu) food, and transportation; the dolmus system of minibuses (below) is especially effective.

.

.

The city still boasts, too, an amazing infrastructure of small scale manufacturing. One of these districts, Şişhane (below), which was already a commercial centre in pre-Ottoman and Genoese times, evolved in the nineteenth century into “a 19th century type Silicon Valley” celebrated for its electrical and lighting products.

Since 2006, in a programme called Made in Şişhane, the architect and designer Aslı Kıyak İngin has co-ordinated a series of design mashup workshops to explore new ways to exploit this production capacity. So far, these design collaborations have concerned household artefacts more than urban equipment; but the focus could easily be shifted towards small-scale energy generation, sustainable urban drainage equipment, and food growing structures.

Many of the projects represented at our xskool concerned food. We learned that food security among poor people was an early casualty of a neoliberal economic policy, introduced in the 1980s, that made food exports a national priority. [The food geographer Paul Kaldjian, an expert on Istanbul, has explained that locally available foods become more expensive when markets are ‘opened up’. Prices of locally produced fresh food rise to levels that rich international consumers are prepared to pay – and then, in a further perversion, imports of cheap processed foods arrive to take their place. “It is not that food becomes scarce”, Kaldjian explains, “but the ability of local populations to command access to food is limited. That is how, in the midst of plenty, it is possible for large populations to be hungry, sometimes even to starve”].

For centuries, traditional market gardens known as bostans (see the photograph at the top) satisfied most of Istanbul’s food needs. In 1900, more than 1,200 of these vegetable gardens covered 12 square kilometers in a large area on both sides of Bosporus. Population growth and property development has pushed food growing to the periphery of the city in recent decades – but there are thought still to be 1,000 bostons in the greater metropolitan region on the Asian side of the city. Could the city, conceivably, regain a degree of food sovereignty by reviving the bostan infrastructure?

Although the centre of Istanbul today looks totally built over, especially in the western part, there is still much potential to use a multiplicity of small plots that still exist in gaps between properties. Also available, once you look, are liminal spaces associated with mosques, or parks and public land on which a municipality may tolerate small-scale agricultural production. Other leftover spaces include land that is difficult to develop commercially because of steep terrain, such as ravines.

A revival of interest in small-scale food growing is a sign that some people in the city are motivated to reconnect with the bostan tradition. In a recent urban permaculture workshop in Istanbul, citizens learned how to survey a small plot of land and were taught what food-growing techniques might work best there. The Permaculture Institute of Turkey (PCI) is now developing a course called Practical Permaculture for Home to support practical ways permaculture can be implemented in urban houses and apartments. Its developer, Senem Tufekcioglu, told me that the clourse is “designed for the city life, and targets women in particular” .

[Turkey’s PCI is organising its first international conference and convergence this year – the first Mediterranean Regional Conference in Istanbul on 24 July]

The Earth Association has also launched a new programme to help people grow food on ledges, balconies, and small plots. Their City Gardens project (see below) distributes seedlings free of charge, stages communal meals, and organises meetings for growers to share experiences.

Some established green enterprises, such as gardening bazaars, nurseries and seed exchange, have survived the carnage of over-development. A key role here has been played by Buğday Association for Supporting Ecological Living. Founded 20 years ago by Victor Ananias, Buğday’s work encompasses organic agriculture, farmers markets, agro-biodiversity, seed-sharing, eco-tourism,and urban agriculture (see below).

Buğday’s first 100 percent ecological farmers’ market was founded in Şişli in 2006. Starting with 48 stalls, the market expanded to 250 within four years. Three more farmers’ markets have since been established in İstanbul, as well as in other cities such as Antalya and Samsun. These markets, whicu are now outlets for 200 kinds of produce grown on land farmed by 15.000 farmers, aplay a key role in the conservation of traditional production processes which is a Buğday priority.

In the association’s Seeds of the Future programme, local seed varieties such as the ‘Kavilca wheat’, the ‘crazy pea’ or the ‘pink tomato’, known and sown for hundreds of years, are shared and distributed. Buğday also runs a rural hub, the Camtepe Ecological Center, whose building – built with local, nature-friendly materials – combines both traditional knowledge and modern conveniences, such as a solar-powered water system. Several blacksmiths and masons in the region were involved, therebyhelping to pass on traditional handiwork skills.

Centre and hinterland

But a reality check is in order. In 1970,Istanbul had two million residents; the figure now stands at more than 13 million – and continues to rise. Nobody suggests that a population of this size can be fed from a mosaic of small plots and rooftops.

On the positive sure, however, flourishing connections between city people, and food growing communities in the rest of the country, are far stronger in Turkey than is the case in northern Europe and the USA. At least one third of our xskool participants, for example, said they could re-connect, if need be, with family farms away from the city. On the edges of the city, indeed, where people from rural areas have arrived more recently, many peri-urban communities import food directly, on a substantial scale, from the rural hinterland they had come from.

This raised an interesting question: if, in the future, Istanbul will feed itself once again on mainly Turkish produce, directly procured, what new forms of solidarity between city and country could be developed to prepare for that?

In a project called Virtual Chef, (see below), the artist Julie Upmeyer has investigated new ways to nurture the knowledge that people in rural areas have about growing and preparing food. As one participant suggested, “we should each ask our grandmother for a lesson like this before their knowledge is lost”.

From seeds, to meadows

The outcomes of an xskool include, ideally, a shared perception of new opportunities; a good idea of how to make them happen; and new connections between motivated and effective people. The short event in Istanbul could only be a taster of such a process, but the city seems like fertile ground. It will be for local actors, such as the Sustainable Film Festival collective, to decide whether to try the experiment again. We’ll keep you posted.