The criminal over-development of the Canary Islands – and the loss of biodiversity and social capital that followed – was financed by the same banks and speculators that our governments are now trying so desperately to save.

Given the desecration of these beautiful islands, the bankers who financed it all do not deserve to be saved. A more fitting fate would have them turned into biomass and returned as fertiliser to the land they have despoiled.

These uncharitable thoughts are prompted by my visit this week to the second Biennale of the Canary Islands Its theme is “Silencio” – but it took me a while to get into this spirit on arrival at Tenerife’s northern aiport: builders were cutting through marble using unmuffled saws, and a massively over-amplified PA system further jangled the nerves.

Away from the un-silent din of Arrivals, the scope of the biennial is impressive. A 200-page catalogue lists dozens of events to do with architecture, art and landscape design. Many excellent and charming projects have been developed as modest interventions.

But taken in total, the attitude (in writing) of the professionals is dispiriting. There are endless riffs of the kind, “the vertiginous pace of development/consumption” – but no self-criticism by designers that their profession has played an important role in all this this ecocidal development. (I do not exclude myself from the guilty, having flown in-and-out in too short a time).

The biennial aspires to chart a new design course for the islands – but one would pay more respectful attention to these proposals if they were preceded by the occasional *mea culpa*.

Just as films don’t get made without a script, urban development doesn’t happen without a “design vision” to inflame the lust of investors.

[ The Canary Islands are not unique in this. During the now-dead boom decades, many illustrious names in design were iimplicated in awful projects. One Dubai property developer teamed up with Giorgio Armani, for example, to build a US$43 billion luxury development on two islands – Bhudal and Bhuddo, off Karachi – that government officials described as being ‘deserted’. But the livelihoods of 500,000 fishermen and their families – indigenous people who have been living on the islands for centuries – will be destroyed if the development goes ahead ].

A particular problem in the Canaria Biennial is one of language. Architects have the irritating habit of writing about development in a third-party, mock-dispassionate manner. The Canaria catalogue is filled with such phrases as “a series of infrastructures has arisen” or, “economic development brought about serious consequences” – as if designers had no connection with these outcomes.

It would have been far better to say, “Mr Planner X was responsible for this awful highway” or “Madame Architect Y created this terrible hotel”.

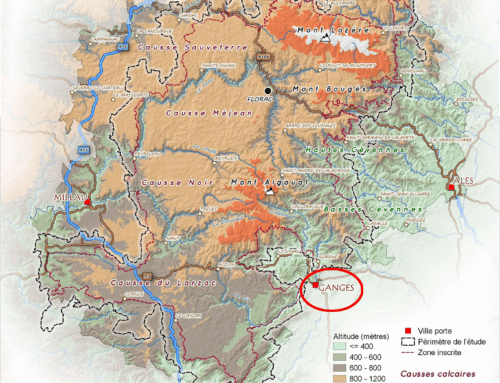

But back to the many pluses. An Ecoclimatic Atlas of the Canaries is just one among several mapping projects that begin to document biodiversity assets that, until now, have been trampled over by development. La Palma has been designated a World Biosphere Reserve, and a series of observatories is to be established to keep an aye on sensitive sites in real-time.

I especially warmed to the idea of a “touring ecomuseum” whose objective is to help people get out of their offices, universities and design studios – not to mention biennial art galleries – to experience endangered nature first-hand.

A exciting project called Proceder (transl: “proceed”) – whose founder Alfonso Ruiz hosted my visit to the biennial – explores the use of ecodesign in sustainable local develpment.

Proceder’s coordinator, Carlos Jimenez, told me about an event called Guia Campus – see pic below – in which ninety designers from a variety of disciplines spend a fortnight each year in a small village Santa Maria de Guia each year. During the event, they develop new ways to enhance the human and natural resources of the territory – designing with, not for, local citizens.

SANTA MARIA DE GUIA

A moving story concludes the Biennial catalogue. It’s about an artist’s grandfather who, when he felt he was dying, went out into the garden and hugged each one of the trees there. He bids them farewell before returing to his bed in the house to die. Somehow I don’t see the next generation hugging the vast Calatrava auditorium when their turn comes to depart their beautiful island.