I did a 30 minute talk last October for Allan Chochinov’s Products of Design class at the School of Visual Arts, in New York City. Here is the video – and below are the main points, followed by a transcript.

MAIN POINTS

You and I use more energy & resources in single month than our great-grandparents used during their whole lifetime.

And we’re doing so on a finite planet.

The science says we can thrive in future – but only if we meet our every day needs using five percent of the energy and material throughputs we’re using now.

That’s a Factor 20 reduction.

That number sounds impossible, so scientists don’t talk about it much.

Their reticence is easy to understand. What is anyone supposed to do with that information?

Good news: examples of a five per cent future already exist: it’s how the world’s poor people already live.

More good news: 95 per cent of the world’s economic activity is already local.

Some advice, in that context, for designers in search of something practical to do: go and learn about poor-to-poor infrastructures that already exist – and use your design skills to enhance them.

Three takeaways:

1: Local provision is not a design or lifestyle choice – it’s where we’re headed anyway. That’s because local uses time, space and energy in radically less wasteful ways.

2: The vast majority of economic activity to meet daily needs is already local. Changing the word faster, to closer,is not as hard as it sounds.

3: Restoring our own health, and caring for place, is a single story.

TRANSCRIPT

WHY “BACK TO LOCAL”?

I’ve been trying to figure out two things: why are all these bad things happening in the world? and, is there something practical that designers can do about it?

The first question, I have to say, has proved easier to answer than the second one – so I’ll keep my first answer short.

What’s happening is summed up, for me, in this pair of images.

Once all the systems, networks and gadgets of modern life are factored in – the cars, planes, factories, buildings, infrastructure, heating, cooling, lighting, food, water, hospitals, information systems, and their attendant gadgets – well, a New Yorker or Londoner today ‘needs’ about 60 times more energy and resources, per person, than a hunter gatherer did, 10,000 years ago.

To put it in a shorter timeframe: you and I use more energy & resources in single month than our great-grandparents used during their whole lifetime. And we’re doing on a so on a finite planet. So that’s the “why”!

I first heard about these alarming numbers 28 years ago in Amsterdam. I was the new director of the the country’s national design institute, and the eminent scientist you see here, Leo Jansen, had agreed to brief me about the latest sustainability research .

”We’re over-consuming resources by a factor of 20 times more than the planet can carry” Jansen told me. “We need to meet our every day needs using 5% of the energy and material throughputs we’re using now”.

My jaw must have dropped because he emphasised to me that the number was not plucked out of thin air. A global network of scientists had been working on the subject for 30 years, and the book Limits To Growth had been published in 1972. That book – 50 years ago – contained scenarios about “overshoot and collapse” of the global system by the middle part of the 21st century – i.e. right about now!

Impressed by that dramatic number, I set out to share Leo Jansen’s dire warnings with people like yourselves in the design world.

I would usually start with some charts and numbers – and I can’t break the habit, so here’s a new doomer chart from just last week: We’ve emitted the same amount CO2 in 12 years, from 2010-2021, as the total emitted from the start of the Industrial Revolution till 1971.

Oh. My. Goodness.

If you’re wondering “what am I supposed to do with that information?” – well, join the club!

I spent a decade, after that meeting with Prof Jansen, wagging my finger at smart and often powerful people telling them that “This cannot go on”.

But in the absence of guidance on what, practically, to do, my dramatic exhortations caused much shrugging of shoulders, but very little actual change.

Repeating the proposition that growth is killing the planet also fell flat.

That statement is probably true – but when many people hear the words “no growth” they think, “no jobs”.

Demanding an end to growth – but without addressing people’s concerns about jobs and security – was a recipe for the blowback we duly experienced.

For a while, the certainty that we’d never make it to 5% turned me into a confirmed doomer. I dreamed of heading for hills in a pickup truck filled with peanut butter.

But before I could flee, I learned of an explanation why the world found it so easy to ignore the dire warnings of people like Leo Jansen.

This is the existence of a “metabolic rift” between man and the living earth – a kind of ecological amnesia triggered, on a mass scale, by modern life.

A combination of paved surfaces, and pervasive media, have shielded us from direct experience of the declining state of the soils, oceans and forests.

We read about it – but we don’t feel it.

I see hope in this explanation. If the core of out environmental problems is separation from nature, then surely we can take design steps to fix that.

My second reason for hanging in there: It dawned on me that examples of a 5% future already existed.

They are everywhere to be seen. Indeed, a big majority of the world’s population meets needs its daily life needs in radically lighter ways than our own.

The diverse ways poor people meet their daily needs are usually described as impoverished, or backward. But in 40-odd years as a guest in what used to be called the developing world, I came to a startling conclusion: living sustainably is how people survive when they don’t have access to the high entropy support systems of the industrial world.

I then began to notice a third thing. If you add up all the activities that people do – and leave aside the abstract numbers of GDP – well, 95% of economic activity is already local, as well as light in its use of resources. The small farm, corner shop, doctor, builder, carer, street trader.

Around the world, hundreds of millions of small and medium-sized companies operate within radius of fifty kilometers of their base. Many of these local communities operate at 5% of the energy levels needed to run the integrated systems of big cities.

Furthermore, people who live locally know far more about their place than we rootless, hyper-mobile moderns do. They can touch, learn about, and care for the places where they live.

Unlike the abstract words that keep us awake at night — words like ”climate change” or “sustainability” – places connect us with life. That’s why some people call their places lifeworlds.

I began to ask: How might we learn from—and improve—the ways that poor people live?

For more than a decade, I sought those who are creating viable alternatives, and present those stories in the Doors of Perception conferences. Stories about real people doing real things transform the idea of what’s possible. The local is shaped by actions, not concepts.

Then came another realisation. A lot of the work people do locally is unpaid. It doesn’t register as GDP at all, because it involves care.

Care is the essential activity people have always undertaken to raise and educate their families, cultivate their land, and support each other in times of difficulty. Mutual aid, in different forms, occurs throughout human history.

Whether it’s cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, ironing, consoling, caring for others, listening, value arises from relationships. not from things.

Fostering better relationships – and creating new connections where there are gaps – is one of the main design opportunities in local places.

These relationships among individuals, groups, networks, and cultures, make up what Cormac Russell calls associational life. It’s how billions of people with low cash incomes meet daily life needs outside the money economy through traditional networks of reciprocity and gifts. They survive, and often prosper, within social systems based on kinship, sharing, and myriad ways to share resources.

Modern healthcare is an example of the exact opposite. Tthe U.S. spends just 2.5 percent of its gigantic health-care budget on public health – even as preventable diseases and ‘pre-existing conditions” have mushroomed. Our neglect of public health has contributed to the millions who have died during the pandemic. It looks like an impossible tangle to solve – until you shift the frame

Ninety five percent of person-to-person healthcare happens outside the bio-medical system portrayed in that nightmare chart — in the home and in the community. But this social dimension receives almost no attention because so much of it is unpaid. It’s care.

This is why I propose a language hack.Let’s call call the world’s small farmers, parents, and cooks, who give us good food, “health professionals”. And let’s call those in the medical world treat consequences, but not causes, “sickness professionals”.

The lesson for local design? Health and wellbeing are not something ‘delivered’, like a pizza – or ‘produced’, like a car. But there’s still a huge amount design can contribute.

Platforms and practical measures can be designed to support the people who already do the bulk of caring, and will continue to do so – from child care, to dementia support.

Go and learn about ‘Poor-to-poor’ infrastructures – and then figure out how to improve them. A green thread connects these stories: Caring for the health of a place, and of the persons who inhabit it, are parts of one story.

PEOPLE DOING LOCAL, NOW

The physicist Ilya Prigogine put it beautifully. “When a system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence have the capacity to shift the entire system”.

Millions of small-scale experiments, and new ways to meet daily life needs, are emerging throughout the world now. The opportunity before us is to seek out these projects, – these islands of coherence – in our own situation and develop practical ways to help them thrive, and interconnect.

This is what I do as a writer. I search for small islands of coherence – that I can later describe – in which social and ecological relationships thrive together.

My aim as a curator is similar – only I don’t just describe projects, but enable embodied encounters between project leaders so they can help each other.

The design opportunity here is more brownfield than blue sky – but no less creative and challenging for that. Help these small islands do better. That’s local design! Local design in this context – economic re-localization in the language of

policy – is a matter of discovery, not invention on its own. But it can still be a creative as well as systematic process.

In Preston, for example, the city measures where resources come from identifies leakages in the local economy, and explore how these leak might be plugged by locally available resources.

I could for hours about projects that inspire me, and give me hope – but I’ll mention just three,

Taobao Livestreaming – direct contact between farmers and the city

Algae Lab vessels – biodesigned vessels to eat the food from

IoT Compost sensors – to manage urban compost heaps

There are 100 other examples here

ENABLING CONDITIONS FOR LOCAL DESIGN

Part 1 = why local – headed to Factor 20 | 5% solutions anyway.

Part 2 = people doing work now.

Part 3 = enabling conditions for this work to be done far more widely + the new skills and practices designers will need to be part of it.

For biologists, the health of an ecosystem lies in the vitality of interactions between its component species. This lesson applies equally to a locality. The process enabling diverse stakeholders to work together is a key success factor.

This chart sums up what design for local is mostly about.

Scanning and Mapping Identify opportunities for local provisioning. Search for neglected value – overlooked people, places practices. Discover what is. Explore “what if?” Keep track of where resources come from, identify leakages in the local economy. Explore ways to plug them using local skills and resources

Curating and Convening Local cannot successfully be addressed without the engagement of all the actors concerned. A variety of different stakeholders – formal and informal, big and small – need to to work together. The question – and it is also a design question – is how Designing the process by which groups work together is just as important as deciding what needs to be done, if not more so

This work is connective. As collaboration experts – people who connect people – the designer curator’s most valuable skills are hosting, convening, facilitating, animating, and co-ordinating.You can learn these skills on courses like The Art of Invitation or The Art of Hosting

There’s been an explosion of new social and business models in recent times. I won’t try and explain them all now. Just be aware, as you begin to design at a local level, that they exist.

Social and ecological contexts are complex. The closer you get to a local situation, the greater diversity of ways to learn about it, to know it. This is a positive: In nature, diversity is healthier than order, control & uniformity. But it does mean that there will be no universal “solution” to fall back on in your design.

On the contrary, you will need to work with other kinds of knowledge than you are used to.

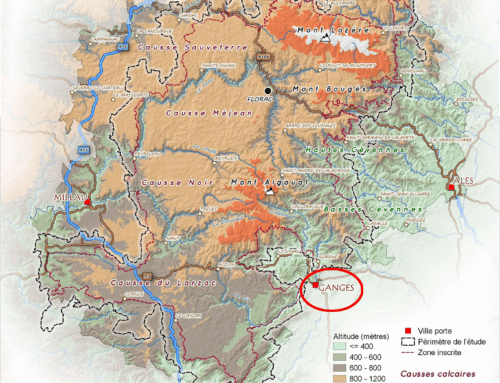

The deep history of a place — its geology is one example. The Deep

Time Walk, or the Atlas at Luma Arles, are examples of deep design awareness in practice.

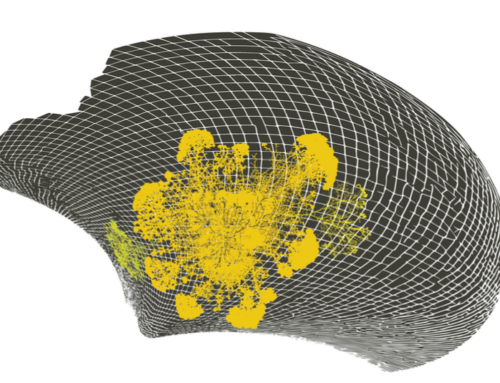

The invisible microscopic life of a place is vital to understanding it, too. 95%

of life is invisible. Many disciplines are involved in ecological restoration.These two ecologists are taking soil samples – and on he left are some of the hundreds to

techniques and technologies available for them to draw on, later.

Restoration may also need a geographer’s knowledge of territory; the biologist’s expertise in habitats; or the economist’s ability to measure flows and leakage of money and resources.

The new local economy reveals its greatest potential when we take inspiration from skills and practices that may already be there, but hidden. Deep ecological knowledge is a feature of indigenous cultures. Australiai’s indigenous peoples have cared for place as a commons for at least 50,000 years

In African cultures, there are an estimated 3,000 different words for sharing. And in Latin America, alternatives to development include the concepts Buen Vivir (The Good Life) and Planas Vida (Plans for Life). These worldviews hold much that we might learn from today.

The best available knowledge is not just found in scientific literature, but also among local stewards such as fishermen, farmers, birdwatchers, urban dwellers and others who interact with ecosystems on a day-to-day basis. Local stewards hold fine-grain knowledge about ecosystems and social ecological interactions.

We need to ask: who has answered a similar question in the past? How might we learn from, or piggyback on, what worked before?

A lot of these knowledges have potential to enrich what we mean by “green new deal”.

Place provides the frame and focus – but history can be a rich source of inspiration. The sharing economy, for example, has been greeted in the Global North as a novelty in recent times—but solidarity systems have existed for centuries. Ever since water was shared as a common resource in Iran 8,000 years ago, people have been collaborating and sharing resources to better raise and educate their families, take care of the land, and support each other in times of difficulty. The mutualization of risk among traditional networks of reciprocity and gift dates back centuries.

Social infrastructure

The journey back to local is a demanding one in terms of knowledge.

Healthy local systems are small scale, and there is no universal best-practice we can apply. A new kind of infrastructure is needed – social infrastructure – to help us grapple with these new questions.

Platform cooperatives, especially, are effective ways for different actors and stakeholders who need to work together.. Platforms can also provide fair compensation for services provision among the people who make those services valuable.

This learning challenge is not unprecedented. The transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy also entailed a profound transformation of knowledge and practice – and numerous regional institutions were invented to ease our transition.

A surprising number of these institutions still exist, and can be repurposed for today’s transition. There are more public libraries in the U.S.A. (120,000) than there are McDonalds

Regional and specialty museums are looking to redefine their roles.

Thousands of post offices and local shops already act as place-based meeting points; we can use them, too, as hubs for learning networks.

Technology has an important support role to play as the supporting infrastructure needed for these new social relationships to flourish. The re-emergence of gift exchange can be made possible by electronic networks. Mobile devices, and the internet of things, make it easier for local groups to share equipment and space, or manage trust in decentralised ways; technology can help us transition from an economy of transactions, to an economy of relationships. Technology can help reinvent cooperative practices in rural contexts: sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting, exchanging, & swapping – in which money is but one means among many of holding or exchanging value.

TAKEAWAYS

Takeaway 1: Local provision is not a design or lifestyle choice – it’s where we’re headed anyway. That’s because local uses time, space and energy in radically less wasteful ways

Takeaway 2: The vast majority of economic activity to meet daily needs is already local. Changing the word faster, to closer is not as hard as it sounds. + Fun Exciting Cool

Takeaway 3: Restoring our own health, and caring for place, is a single story.