A new course in Sweden poses the question, “what will a self-sufficient Hällefors Municipality taste like in 2030?”

Students on the course act like talent scouts. They search for unrealised food-growing potential across the region – people, unused land, forgotten traditions.

An example could be a farmer who’s started to grow heritage wheat, but cannot find customers. Or a school teacher who wants to connect his students with a working farm.

A student might spot an abandoned field near her home and and explore new ways to grow food there. Another might develop snacks to sell to a mountain bike business in the forest.

At the end of each course, students pitch their ideas to real-world professionals – for example, chefs, farmers, or food production businesses.

Chef Paul Svensson, who’s teaching on the course, is a ‘connector’ between the course and potential partners. The best ideas will be developed as product and service prototypes with help from Örebro County and other local food system actors.

For course leader Annika Göran Rodell, a priority is to develop new collaborations between academia, municipality and business. She is optimistic that the best student proposals can generate new livelihoods or be developed into new companies.

The course prepares Orebro County for the near the future – but it also takes inspiration from the past.

Students explore what was grown or eaten 250 years ago – and how – and come up with new ways to grow, prepare and serve forgotten staple foods.

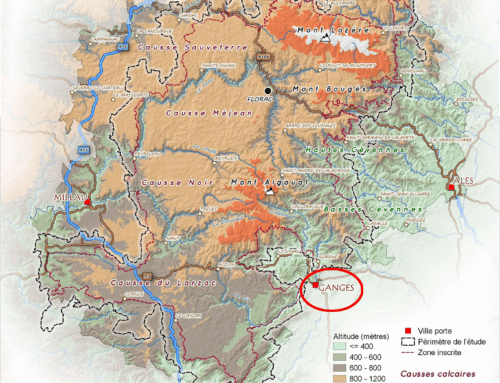

Mathias Lindberg, a local entrepreneur, has prepared the ground by “looking in the rear view mirror. What did it look like here 250 years ago? We see a plate that was rich in fish, poultry and vegetables from the municipality”.

In this way, inspired by how people lived the end of the 18th century, students are enabled to compare that time with today’s conditions. Students work on the gastronomic potential of unfamiliar or disliked foods – many of which used to be staples in local diets.

More recent history can also be an inspiration. In the early twentieth century, the area around Hällefors was a mining region. As one local historian told this writer “back then, everyone grew”.

On a pilot of the course last year in Grythyttan, students came up with new ways to cook roach fish. Roach is a delicacy in other countries, but has fallen out of favour in Sweden.

Students did not only develop new ways to serve roach. They also used the meal to celebrate the ecological restoration of the region’s lakes.

Peas, too, were a staple crop for millenia before the global food system arrived. Making these staple crops delicious is an important contribution to food resilience.

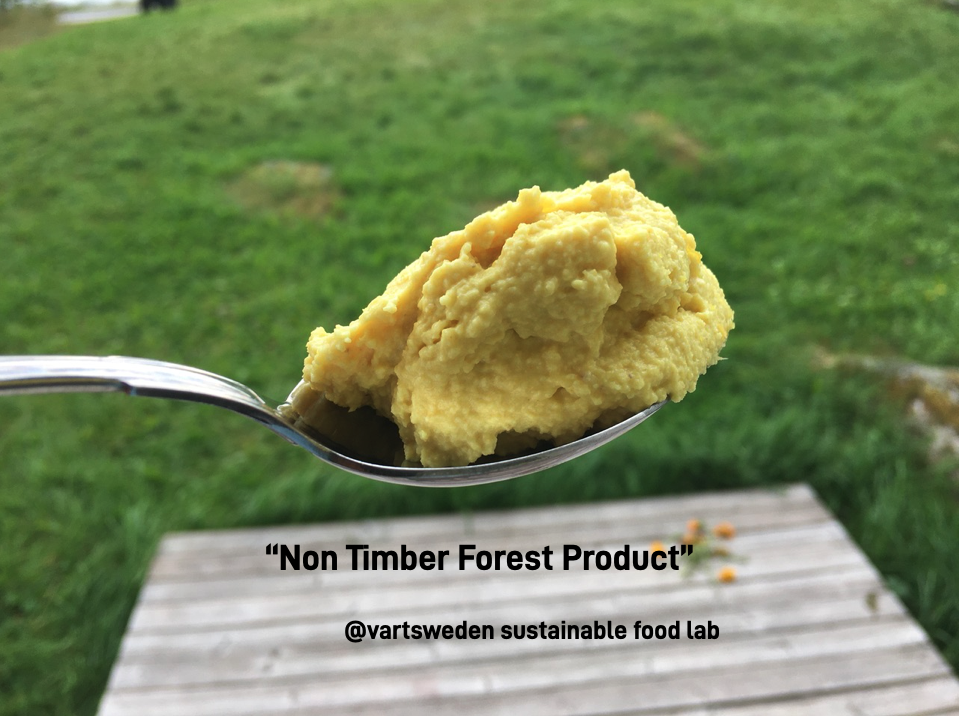

Dr Magnus Westling, a noted expert on the history and potential future of the pea is working with the founder of a food lab, designer Corina Akner, on hummous made with yellow peas.

“Wine people pay close attention to the ’terroir’ where a grape is grown” says Westling, “The influence of climate, landscape, soil, and geology on how a wine finally tastes. We are developing a similar appreciation for cereals, or peas – and the new course is part of that innovation”.

“Working with food is a life-giving process. By training as chefs and sommeliers, our students play an active role in ecological restoration”.

Hjulsjö 103

Magnus Westling is a chef with several hats. Together with his partner Marta Westling, a prize-winning baker (see photo) he also runs Hjulsjö 103 a small family run cider house, sourdough bakery and coffee roastery

“With the Bergslagen forest as our closest neighbour, we explore what can be created out of a selected few, regionally-sourced products”, Marta explains. “The grain, the apple, the cheese: they have longstanding history of cultivation and rich taste”

In their ongoing exploration of traditional food varieties, Marta and Magnus have learned about historical patterns of agriculture, meal cultures, craftsmanship, traditions, and biodiversity in food production and consumption.

Her constant search for new ingredients also brings Marta in contact with farmers across the region. She is also active in a growing network of fifty ‘real bread’ bakers around the country.

In only a few years, Hjulsjö 103 has become a de facto rural innovation hub.

Non-Timber Forest Experiences

Christina Schaffer, at Sweden’s University of Agricultural Sciences, has been investigating an ecosystem-based approach to the forest economy for her PhD. Schaffer’ applies an ecological vision to sustainable forest management. Her approach involves adopting the natural forest as a model, and creating a managed forest that helps maintain biodiversity.

Sweden used to have thousands of ‘forest farmers’ – and that tradition is emerging once again. Forest farming, silvopasture (grazing livestock), forest gardens, and alley cropping, can all be viable alternatives to a timber extraction economy, Schaffer has found.

As students in Hällefors Municipality develop new uses for berries, leaves, elk, and boar, the hope is that their interest will encourage a new generation of forest farmers to try other experiments, too – by growing new kinds of nuts, fibers, and dyes.

“Historically, forest farming was always multi-use” Schaffer explains. She has concluded, now, that the economic category “Non-Timber Forest Products” could be much more varied than it is at present.

Back To The Land 2.0

Schaffer poses this potential as a challenge to designers on a summer course called Back To The Land 2.0.

Hosted by the design school Konstfack, in Stockholm, designers on the the six week course develop a variety of service and product ideas ideas to do with Non Timber Forest Experiences.

As these diverse experiments diversify, and deepen, the vision of a resilient cluster of municipalities on Örebro County is coming into focus.

But it’s not not just a vision. By turning ‘would-be-nice’ ideas into tangible prototypes and scenarios, design has shown that it can catalyse the emergence of new livelihoods and jobs. This turns the notion of a just transition from an aspiration into a practice.

A missing element in Back To The Land, until now, has been a ‘client’ in the region, to whom the design proposals are given when each the course ends.

The cluster of initiatives described in this story are taking shape as that ‘client’. Together with Konstfack (which has just launched a new Design Ecologies Master’s Programme )a discussion has started about the kind of platform, based in Örebro County, would best support relationships among these actors and stakeholders, going forward.

The author publishes this Back To The Land Reader each year.