In 1990, Japan was at the height of its ‘bubble economy’. It popped, spectacularly, two years later. This text was originally published in The Listener, in the UK, in 1990.

In Tokyo, cement trucks sport the slogan, ‘Begin The Next’. Buy sellotape at the cornershop, and the bag carries a slogan: ‘Perhaps We Are At The Beginning Of A New Renaissance’. Ride Honda’s new Dio motorcycle and an entire text on the faring declares ‘Movement. The City is a 24 our stage where we act out a life. Be it day or night, we go out anytime looking for something new’.

Hardly surprising that they call Tokyo: the Sea of Desires: its citizenry revel in continuous change and innovation. In the West, we whinge about our insecurity and the ephemerality of all we hold dear; in Tokyo, they exhilarate in the perceptual white noise of an information-rich environment.

Small wonder that the city has become the centre for a new phenomenon: post-modern tourism. Tokyo today is like America during the 50s: you go there to wonder, childlike, at a fantastical world where everything works – only in Tokyo’s case, it’s not just the phones, but a whole new culture.

Getting Real

Scene: the basement of Cleos, a very dingy night-club in Roppongi, Tokyo’s fashion and entertainment district. By 3am, Cleos is packed, its clientele almost exclusively Western models, photographers stylists and other camp followers of the fashion circus. They drop ecstasy and acid like popcorn, dress real cool in expensive rags. But their confident, self-contained, manner cannot disguise the sense of desperation: there’s panic in the air. Even the hard ones are Tokyo crazy.

Here to take an estimated ú25 million a year from Japanese magazines and ad agencies, this latter-day cultural diplomatic corps is in town to practice the black arts of consumer deception – to make a thousand advertising images in which they frolic, ultra-white, Aryan goody-two-shoes, stars of a fantasy Western culture that would be laughable were it not for the fascistic overtones. But in Tokyo, simulation is in the blood: not for them this fear of a three minute culture or the ‘disappearance of the real’. Psychologically, Tokyo is like New York: you have to be born to it, or it takes a toll.

The new geography

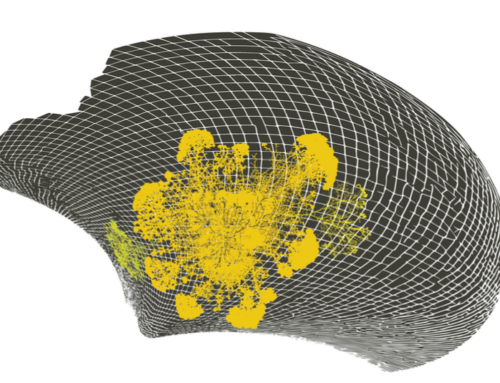

Scene: any street. Tokyo lacks a visible plan, of the kind that we choose to find reassuring in London, Paris, or Vienna. Tokyo is the paradigm of the modern de-centred metropolis. It’s not so much that it disorients you – you never get oriented in the first place. Tokyo is a place-by-place place – how location relates to the last remains obscure. Lacking vistas, and grand plans, you have no sense of travel between points: rather, you leave one experience, and start another somewhere else. The intervening motion is out of place and time.

Europe’s boulevards and ringstrasses were built by tearing the hearts out of the old town; Tokyo, in contrast, has evolved chaotically. From the top of Tokyo Tower, you see none of the neat radial lines that denote the hand of one dictator or another in Europe – the ‘Great Weavers’, as Giles Deleuze calls them, bulldozing wefts and warps across whole districts and underclasses. Tokyo is a patchwork, added onto bit by bit.

Soft Buildings

Post-modern Tokyo has fostered a remarkable design and architecture revival – but you have to see it in context. Over here we remain in thrall to the stereotype of Japanese design as exquisite minimalism. This idea is the legacy of work during the 70s and early 80s by architects like Tadao Ando, who refined an aesthetics of order and designed perfectly-formed little worlds (and some big ones) as refuges from the chaos and disorder of the street. Ando’s stark, concrete walls and interiors are a miracle of spatial control, and they’re beautifully finished – one reason his work speaks of heaven to the Western modernist – but it’s not what Tokyo, now, is about.

The sea-change was marked for some by a famous row when Nigel Coates was hired to design the interior of an Ando building. Coates represents not just western street credibility, but, more importantly, a less negative approach to change, an attempt not hide from, but to welcome, change.

The new sensibility according to Ke’iche Irie, one of several brilliant new architects to challenge the old guard, ‘values the fact that Tokyo is like a computer program that ceaselessly keeps on adding new subroutines. Western language itself, and your aspirations for buildings, which both emphasise order and clarity, seem now, to us, to be like a straitjacket. We don’t believe in moulding life to the straight lines of an ideal building’.

The new architects flourish on a diet of theory, fashion, and stupendously rich clients. The reason: so heated is Tokyo’s real estate boom (Docklands is like a village fete by comparison) means that any device that can add value to even small patches of land is worth paying for. Hence the concept of buildings as ‘news’ – objects possessed of sufficient design or fashion charisma that they attract attention to the surrounding area which becomes smarter – and more valuable. In Roppongi, for example, one developer spent $40 million on a night-club, Turia, that ‘paid’ for itself before its doors even opened – just because adjacent small lots, which he also owned, shot up in price.

Comme Des Fire Hydrants

Another star of Tokyo’s building-as-icon boom is Shin Takamatsu, famous for designing a dentist’s studio in Kyoto that looked like an aluminium steam engine, and a club in Osaka that looked like nothing on earth. It is extremely satisfying to discover that Takamatsu live matches one’s fondest stereotype of a fashionable Japanese architect – dressed from head-to-toe in Comme des Garcons, surrounded by an entourage of beautiful assistants, and ready to drop references to Kafka, Mishima and fractal geometry in conversation. Takamatsu speaks of buildings as objects, well aware that in Tokyo buildings are indeed commodities, bought and sold, made and destroyed in a frenzied bazaar.

But just because buildings are icons, and may soon be torn down again, does not mean they are badly made. On the contrary; although Tokyo’s vistas appear confused – cluttered and insubstantial to western eyes – the quality of detail in things small is a miracle to observe. Door handles, fire hydrants, tiling on doorsteps, all can be exquisite. Even Takamatsu, master of the ephemeral building, points out that ‘hard materials have power: the problem with western design is the poor quality of the facade – in Japan we believe in the concept of deep surface, no matter how short a building’s life’.

Thin Skins and Disappearing Buildings

If the new urban sensibility in Tokyo recalls Marshall Berman’s remark that ‘the modern project is to make yourself at home in this maelstrom, to make it your own, then another of the key players on Tokyo’s urban landscape, Toyo ITOH, is particularly comfortable. Itoh has made flux and ephemerality in architecture the basis of his work. His extraordinary Tokyo Tower in Yokohama, for example, a 100’ high membrane-covered structure, software controlled, changes its very mass according to the wind, amount of daylight, even the density of the crowds which surround it. ‘Our obsession with walls has been replaced by a search for openness and transparency in buildings, to be positive towards the outside world’ Itoh is a leader in the use of thin-skins, or membranes, to make buildings permeable – to make them ‘disappear’, as he puts it. ‘Buildings are like clothes – sometimes we feel sensual, and feel like going naked’.

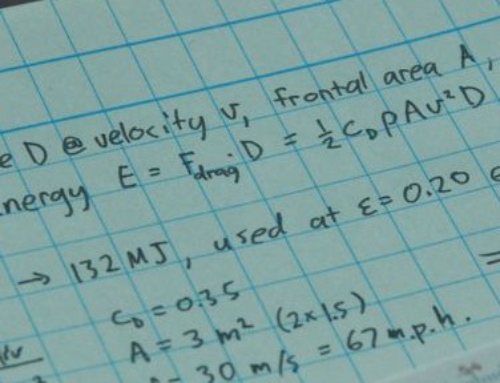

Modern Movements

Getting to one of Itoh’s invisible, naked buildings tends to be a life event in itself. If Tokyo’s overall plan is opaque, its transport arteries are self-contained worlds of their own. Tokyo’s road system strides over the top of the landmark buildings – huge, thick earthquake-proof legs carrying roadways, some of which are hundreds of feet up in the air: as you crawl along in an interminable jam, you can see straight into the 20th floor of the skyscrapers, where thousands, tens of thousands of identically dressed salarymen work away until late at night. This sight alone must dismay arriving businessmen – a vast human beehive buzzing with effort into the late hours.

Another surprise is that the cars are so big. In the central districts, there are hundreds of 560 Mercs with tinted windows – these belong to the Yakusa; recently, so heated has one-upmanship among the gangsters become that they’ve started stretching their Mercs, adding six fur-lined feet or more. They leave them in rows outside the clubs, engines running, keys in the lock – a million dollars worth of that nobody takes.

And the taxis. They’re all called Cedrics, or Glorias – dumpy great Nissans purring around. You realise that Japan exports all those buzzy little cars to the gullible west, keeping a whole array of heavy, silent, comfortable tanks for themselves. And all so clean: buy a gallon of petrol and a swarm of guys wash the whole car. Taxi drivers wear white gloves – whether to signify hygiene, or as protection from infection, is never clear. Taxi colours, in contrast, are jolly pastels, with Chinese lanterns of the roof. The fancier ones have backlit turquoise numberplates.

Sometimes, when not admiring the cabs, you see – again overhead – the bullet trains heading off for other cities. Twice the size our 125s, the Shinkansen are incomparably more elegant, their rounded brilliant white noses carving through the sky in high speed silence.

Under Ground, Out Of Time

The tubes, as my uncle in California would say, are something else. Tokyo boasts a brilliant, perfectly run system of co-ordinated private lines which is almost completely mystifying to foreigners. Entering Shinjuku Station, a vast 500 acre interchange, you encounter an information landscape of stunning beauty and mystery – tens of thousands of Japanese typographic characters, on signs, on ticket machines, on tv monitors. Beneath them, hundreds of thousands of human Japanese characters move purposefully about, avoiding the foreigners who gaze about blankly, like whales stranded like whales on the icecap.

Even the ordinary tube trains are attractive. Thanks to deregulation, each line has its own company colours – but whatever the livery, trains gleam, as if someone had just polished every handrail. This probably because someone just did. (In department stores, they employ doll-like girls to stand each side of the escalator, polishing the handrails. And you love it. The pathology that afflicts visitors to Tokyo takes strange forms – like turning into your old Auntie Edna who hates litter).

They Nurture Neon

Tokyo’s skyline at night is literally flashy, thanks to the remarkable columns of neon that adorn the sides of most buildings – particularly in Shimnjuku, where the commercial nightlife is based. The sharpness and high definition of these neon signs combines with the squareness of Japanese calligraphy to produce a stunning effect. Many of the signs are programmed, so that bars of light pulse up and down the columns of light like heartbeats. The signs are light-filled analogues of the buildings they are attached to: in Tokyo, shops, clubs and bars are stacked up high, story upon story – the pulses of light going up and down the neon columns remind you of lifts.

But just when you figure out some vague correspondence to what things look like, and the way they are, Tokyo feints. For example, the addresses on peoples’ cards and letters refer to three-dimensional point in space. This is no doubt an extremely sensible system if you are a pigeon, but for the rest of us, it induces, once more, a sensation of displacement. The ritual of following directions (you have to write down verbatim things like ‘head past the red door, turn left at the blue hut and look up for the ‘I feel Coke’ sign – we’re the third window along from that). The fallibility of the system – odds are, someone will have painted the door – ensures that western visitors soon understand eastern thought processes, and in particular their tendency to arrive at a conclusion by a roundabout route.

Word Games

The English are particularly prone to delusion that they’ve got the hang of Tokyo, seeing in its graphic face an echo of their own image-saturated environment. At a club called Piccasso, for example, a boy from London’s iD magazine has been imported to decorate the walls with graffiti drawn words of stunning banality: ‘the more you consume the less you live’; ‘London Town, check it out’; ‘Check them out: Sacrosanct, Soho Brasserie’. Do us a favour. The ‘artist’ has approached Tokyo like a missionary speaking in pigin – words in Tokyo simply don’t work like this. Someone explains: the Japanese use strange English formulations to express feelings, not to describe things – and trying to mimic it is guaranteed to offend.

Consuming passions

Which is not to deny that Tokyo displays all the symptoms you’d expect of a patient neurotically addicted to consumption. In discussions with business people you realise that they see ‘lifestyle’ purely in terms of the products you consume. Companies disguise this behind strange corporate slogans that they add, free of charge, to what is already an information-saturated landscape. Sharp adds ‘New Life People’ to its packaging; NEC: plasters ‘Computers and Communications For Human Life’ on its terminals; JVC, most runically of all, simply says ‘Charming’ on everything. In Tokyo, sociology is a shopping A man from the Hakuhodo Life and Living Institute, shows me a book called ‘Keeping Up With The Satos’, which tells you how many ‘confident theoretical Japanese’ give their grandmothers seaweed for Christmas (56%) – but tells you precious little about how they feel when doing so.

Shopping Software

The overlap between big business, culture and fashion – that is, shopping – takes fascinating forms in Tokyo. Who among us has not yawned as yet another returning Brit regales one with small black toys and cigarette lighters that look like frogs. More interesting, on the ground, are the ‘antenna buildings’ – shops, or galleries – often both – which are subsidised by big companies so that they can observe arcane consumer behaviours – such as buying a Comme Des Garcons chair – and decide if they should join in too. The Axis Building, for example, a four story, tile-clad edifice sitting on $100 million of land in Roppongi, is owned by Bridgestone, the gigantic tyre and car parts business. Inside Axis are a series of rarefied retail experiments – as well as the Kawakubo furniture, there are Nuno Textiles, a lighting workshop – and two galleries, in which a succession of design exhibitions are staged free of charge.

Axis is run by Mr Ishibashi, the urbane, American educated son of Bridgestone’s president – who clearly regards the building as a private finishing school which will train his son to take his empire out of manufacturing and into the information age. And it will probably work: if Ishibashi junior can figure out why people buy Rei Kawakubo’s chairs, he should manage to get Bridgestone out of rubber and into fashion.

Everywhere, unlikely people tell you they want to know how to get into the information era now. A town planner from one of Tokyo’s localities – his equivalent rank in London would receive complaints about dustbins – tells me that ‘we have ten years to complete the transformation of Tokyo from a hardware to a software city’.The architect, Takamatsu, says he sees Tokyo in the future as ‘a cloud, an ephemeral city’.

Info-mania

The only cloud on Tokyo’s rosy postmodern horizon the lowering threat of a terminal information glut. Hiroshi Sakashita, who runs Sharp’s design centre, speaks of information illnesses by reference to ‘the sword and the vase: western thought is linear; you establish a line of questioning, and then attack it straight on, like fighting with a sword. This enables you to ignore extraneous matter. In Japan, our minds are more like a vase, filling up with all the data available – themn we wait to see what grows out of it’.

Information floods Tokyo – visual, intellectual, sensual; this, plus its cartographic obscurity, explains why it is so hard to comprehend as a visual or conceptual unity. Our very vocabulary in the West is spatially biased – we have more words to describe measurements than we have to describe feelings. What we certainly lack is the emotional apparatus needed to understand the interaction of space, time and process that marks out Tokyo, and other post-modern cities like it, as a new phenomenon.

Pondering it all, the dazed departing visitor passes, on the way out at the airport, a graphic symbol of Tokyo’s position at the centre of something we can’t quite put our finger on, a vast map of the world, on which key cities are highlighted not just by names, but by digital readouts of their different local times. Beneath, a single arrow says: ‘This Way’. ends

This was originally published in The Listener, in the UK, in 1990.