This is the text of my plenary talk at the Innovation and Emerging Industry Development (IEID) conference in Shanghai on 18 September 2019. I describe three enabling conditions for system change: a capacity for ecological thinking; a focus on social infrastructure (rather than the concrete kind); and a shift of focus from place making, to place connecting.

A cultural disconnection between the man-made world and the biosphere lies behind the grave challenges we face today. We either don’t think about rivers, soils, and biodiversity at all – or we treat them as resources whose only purpose is to feed the economy.

This ‘metabolic rift’ – between the living world, and the economic one – leaves us starved of meaning and purpose. We have to heal this damaging gap.

My talk today is therefore about the design of connections between places, communities, and nature. Drawing on a lifetime of travel in search of real-world alternatives that work, I describe the practical ways in which living economies thrive in myriad local contexts.

When connected together, I argue, these projects tell a new ‘leave things better’ story of value, and therefore of growth.

Growth, in this new story, means soils, biodiversity and watersheds getting healthier, and communities more resilient.

The signals of transformation I talk about are not concepts, and they are not the fruits of a vivid imagination. They are happening now.

But in conversations about innovation, I am often asked the same question: Are small local initiatives an adequate response to the global challenges we all face?

The sheer number and variety of initiatives now emerging is my first answer to that question.

No single project is the magic acorn that will grow into a mighty new oak tree. But healthy forests are extremely diverse, and we’re seeing a healthy level of diversity in social innovation all over the world.

My second answer concerns scale. Many people – for example in government, or in large foundations – tell me that large-scale solutions are essential if we are to deal seriously with the large-scale challenges we face.

But that’s not how healthy nature works, I answer. Every social and ecological context is unique, and the solutions we seek will be based on an infinity of local needs.

There is no such thing as a correct approach for the whole planet.

My third answer concerns history.

Big transformations in history have seldom been the result of a single cause or action; they were a consequence of multiple, interacting, processes and events that unfolded at different tempos.

The German word eigenzeit – “proper time” – describes this phenomenon well: The timescales of change for a bacterium, a forest, or an economy, are very different – but they are all interconnected.

History also contains numerous examples of profound transformations that seemed impossible at the time – until they happened: the end of slavery in the United States; women gaining the right to vote England; or the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Nelson Mandela’s famous words on the subject – “it always seems impossible until it’s done” – have inspired millions of people – and rightly so.

The assumption that the future is all about cities is another ‘inevitability’ now being reversed.

Designers have taken the lead in rediscovering the qualities and value of rural life.

Design Harvests, for example, led by Professor Lou Lou Yongqi at Tongji University, is a pioneer internationally in the creation of of new links – both cultural and economic – between city and rural.

Enabling conditions for system change

Designing for change, in this context, is less about single, problem-solving actions, and more about the continuous search for value in neglected contexts, and the creation of enabling conditions for system change.

The first and most important enabling condition is a capacity for ecological thinking – the ability to see the patterns of life as a connected whole.

Experiencing the world as a web of connection – between humanity, place and nature – is deeply rooted in Chinese culture, but has been forgotten in most of the West.

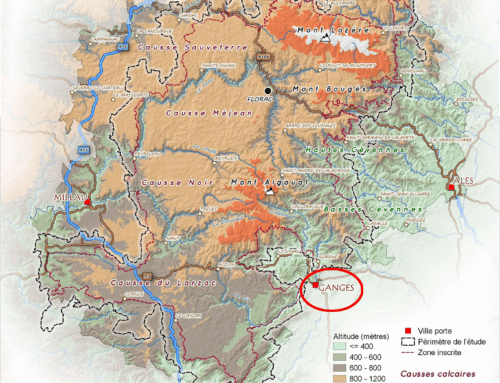

These connections – or their absence – are best explored at the scale of the bioregions that surround our cities.

A bioregional focus re-connects us with living systems, and each other, through the places where we live. It acknowledges that we live among watersheds, foodsheds, energysheds, fibersheds – not just downtown or in ‘the countryside’.

Thinking ecologically gives new meaning and purpose to the concept of growth.

Rather than measure progress against such abstract measures as money, or GDP, growth in a bioregion means observable improvements to the health and carrying capacity of the land, and the resilience of communities.

Value is created by the stewardship of living systems rather than the extraction of ‘natural resources’. The language used is one of system stewardship rather than ‘productivity’.

A second enabling condition for system change is a focus on the social.

In the North, the sharing or Peer-to-Peer economy has been presented as a novelty in recent times – but throughout history, people have collaborated, and shared resources, to raise and educate their families, take care of the land, and support each other in times of difficulty.

Social systems based on kinship, and ways to share resources, have deep roots in China, Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

Although these practices have been neglected during the modern age, they have enormous potential today. We need to ask: who has answered a similar question in the past? How might we learn from, or piggyback on, what worked before?

A third enabling condition for system change design is