In myriad projects around the world, a new economy is emerging whose core value is stewardship, not extraction. Growth, in this new story, means soils, biodiversity and watersheds getting healthier, and communities more resilient. These seedlings are cheering, but when it comes to binding diverse groups together around a common agenda, something more is needed. We need a compelling story, and a shared purpose, that people can relate to, and support, whatever their other differences.

For me, a strong candidate for that connective idea is the bioregion. Beginning with a short reflection on the power of such a story, and what’s already out there, this text describes what the elements of a design agenda for bioregions might be. As a work-in-progress, it will evolve in forthcoming conferences and Doors of Perception Xskools. If staging an xskool could be of interest in your bioregion, do get in touch.

1. A story that connects

2. Scope of a bioregion

3. Learning and design agenda

4. New skills and partnerships

5. Getting started

1. A story that connects

In myriad projects around the world, a new economy is emerging whose core value is stewardship, not extraction. Growth, in this new story, means soils, biodiversity and watersheds getting healthier, and communities more resilient.

These seedlings are cheering – but binding diverse groups together around a common agenda remains a challenge. Words like Sustainability, Resilience, or Transition are evocative – but abstract. Something more is needed: a compelling story, and a shared purpose, that people can relate to, and support, whatever their other differences.

A strong candidate for that connective idea is the bioregion. A bioregion re-connects us with living systems, and each other, through the places where we live. It acknowledges that we live among watersheds, foodsheds, fibersheds, and food systems – not just in cities, towns, or ‘the countryside’.

A bioregion, in this sense, is culturally dynamic because it is literally and etymologically a ‘life-place’, in Robert Thayer’s words, that is definable by natural rather than political or economic boundaries. Its geographic, climatic, hydrological, and ecological qualities – its metabolism – can be the basis for meaning and identity because they are unique.

Growth, in a bioregion, is redefined as improvements to the health and carrying capacity of the land, and the resilience of communities. Its core value is stewardship, not extraction, a bioregion therefore frames the next economy, not the dying one we have now.

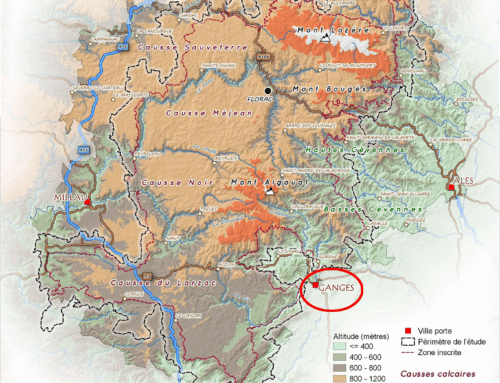

2. Scope of a bioregion

A bioregion is not an abstract model; it describes social as well as ecological systems that are unique to each place. The ways these social and ecological systems interact with each other are as significant as are list of species and social assets.

Stewarding a bioregion involves measuring the carrying capacity of the land and watersheds; putting systems in place to monitor progress; and feeding back results. This attention to ecosystem health is direct and ongoing; it involves diverse forms of expertise; translation skills, and open information channels, are needed to share different kinds of knowledge.

A bioregion provides livelihoods, not just amenity. It builds on existing economic relocalisation efforts that measure where resources come from; identify ‘leakages’ in the local economy; and explore how these leaks could be plugged by locally available resources.

Bioregional food – and health

One such ‘leak’ is food – and new kinds of work are involved in ecological agriculture. This work begins with understanding the soils – and growing crops, and rearing animals, in ways that regenerate them. Each farm has to be understood and designed as an ecosystem within a bioregional web of natural systems. This approach to farming is more knowledge-intensive than the industrial model it’s replacing; multiple skills, in new combinations, are needed to cope with that complexity.

At a bioregional scale, ecological agriculture also includes the development of new forms of land tenure, distribution models, processing facilities, financing, and training. With ‘social farming‘ and ‘care farming’- the direct participation of citizens in farm-based activities needs also to be enabled by service platforms.

Health and wellbeing are local and place-based, too. In place of a biomedical healthcare system designed around individuals and diseases, an ecological model of health gives priority to the vitality of food, water, air and other ecosystems, and intractions among them.

In the US, the idea of a Health Commons has been proposed as a geographical model for improving the health of ecosystems and the people who live in them. The Glasgow Indicators Project is another effort to develop tools that link community health and ecosystem health.

Cities are in bioregions, too

The thinking behind bioregions grew out of the conservation movement in the North Western United States, in the 1970s. It was inspired, then, by the notion of wilderness, and focused on protected areas, biosphere reserves, species conservation, and ecosystem management.

But awareness is now growing that our cities are part of the bioregional story, too – that they do not exist separately from the land they are built on, and the resources that feed them.

Blogs and platforms such as Nature of Cities, Ecocity Design Institute, and Biophilic Cities, although they do not focus on a bioregional perspective, do encourage a city’s citizens, and its managers, to re-connect in practical ways with the soils, trees, animals, landscapes, energy systems, water and energy sources on which all life depends.

The urban landscape itself is re-imagined as an ecology with the potential to support us. Attention is turning to metabolic cycles and the ‘capillarity’ of the metropolis wherein rivers and biocorridors are given pride of place.

3. Learning and design agenda

Many elements of a design agenda for bioregions already exist – but they are scattered, and can be easy to overlook. Scanning for examples of how groups have fared so far is priority No. 1.

Universities across the north-western United States, for example, have developed a Curriculum for the Bioregion that transforms the ways in which tomorrow’s professionals will approach place-based development.

The curriculum, which is taught across the Puget Sound and Cascadia bioregions, covers such topics as Ecosystem Health; Water and Watersheds; Sense of Place; Biodiversity; Food Systems and Agriculture; Ethics and Values; Cultures and Religions; Cycles and Systems; Civic Engagement.

A impressive archive of completed projects is evidence that these are not just academic activities. Multidisciplinary teams have evaluated water quality data as indicators of the health of an ecosystem; mapped stream channels in a local watershed; learned about the geology, hydrology, soils, and slope stability of a local town; analysed the environmental costs of metal mining; studied how indigenous peoples used to inhabit their region – and discussed how best to integrate this legacy into today’s new models of development.

Although the range of topics sounds hard to embrace as a unity, a stand-alone five-day Introduction to Bioregionalism has been trialled by the Continental Bioregional Congress in the US. This programme covers ways to;

– deepen a sense of place for the individual and community;

– develop a bioregional toolkit for allied movements;

– provide a way to certify a level of competence in instructors;

– provide support for local bioregional groups to establish and sustain themselves; and

– strengthen bonds among different bioregional networks.

At the University of Idaho, a Masters in Bioregional Planning and Community Design draws on the expertise of ten departments; there’s the option of a joint degree from the College of Law. The Priest River Bioregional Atlas, created by the university, is one of the more compete documents of its kind out there.

in Europe, an online course called Land stewardship: from theory to practice was produced by the LandLife EU programme. During the course, students presented case studies of land stewardship; designed a stewardship agreement; analysed collaboration methods and communication experiences; and explored funding opportunities for land stewardship.

A Soil Academy is being developed by a group called Common Soil. A Common Soil Campus is proposed as a learning centre for regenerative agriculture, land restoration, regional food systems, and land stewardship; the idea is equip the next generations of farmers and citizens the skills to become stewards of living soil.

In South West England, Isabel Carlisle, Education Coordinator of the Transition Network, has proposed the creation of a Bioregional Learning Centre for (as a first step) South Devon. A series of workshops is under way in which diverse actors – including water companies, transition groups, and universities, are launched to develop a learning and design agenda.

In Scotland, Clare Cooper leads a programme of arts and cultural activities, called Cateran’s Common Wealth, that connects together cultural, social and ecological assets using the ancient metaphorical power inherent in pathwalking and path making to do so.

Asset mapping and monitoring

In traditional place-based development, the outcomes of a site assessment tend to be lists of discrete assets. At a bioregional scale, representations are needed in which the whole is far more than the sum of its parts.

A bioregion’s ecological and social assets therefore need to be investigated, and mapped: Its geology; topography; climate; soils; hydrology and watersheds; agriculture; biodiversity, flora and fauna, vegetation.

A lot of this information exists already – but often in the form of dry, de-contextualised lists. Maps therefore need to represent the ways systems interact with each other, not just component parts. These maps also need to be dynamic and reflect change, as much as possible, as it happens. They also need to support social processes of collaborative monitoring, and feedback.

For the eminent American designer Hugh Dubberly, in his manifesto for systems literacy, whole system change is “not so much hard to do, as hard to see”. System structures are more easily described and understood as images than as words, he explains; through diagramming or mapping, we can share our mental models, our diagnoses, and our plans.

The social assets of a bioregion – individuals, groups, and networks – also need to be made visible. Social assets also include places that support collaboration – from maker spaces to churches, from town halls, to libraries.

One exemplary example known to this writer is Visible Mending Everyday Repairs in the South West. In this project, two cultural geographers and a photographer visited workplaces in South West England; their texts and images explore the practices of fixing, mending, repair and renewal. Another fine example – Make Works, in Scotland. is a curatedf finder service and web platform for people who need to get things made.

Maps are also useful in plotting the footprints of government agencies who manage different parts of a landscape. Or not: These exercises can often reveal gaps. In Stockholm County, for example, a wetland management network crossing all 26 municipalities was found to be fragmented not just ecologically, but administratively, too.

Role models and case studies are always important. ‘Mapping’ therefore includes multiple ways to collect and tell stories from other places – and other times – in ways that are easy to find, and share. A lot of information about a bioregion’s social, cultural and ecological assets can be discovered in overlooked archives and databases, for example; wonders can appear when artists or actors are allowed access to these kinds of resources.

Identity

A large topic, simply stated: What would a bioregion look like, and feel like, to its citizens, and visitors?

4. New skills and partnerships

Developing the agenda for a bioregion involves a wide range of skills and capabilities: The geographer’s knowledge of mapping; the conservation biologist’s expertise in biodiversity and habitats; the ecologist’s literacy in ecosystems; the economist’s ability to measure flows and leakage of money and resources; the service designer’s capacity to create platforms that enables regional actors to share and collaborate; the artist’s capacity to represent real-world phenomena in ways that change our perceptions.

5. Getting started

Designers and artists can contribute to bioregional development in various ways. Maps of the bioregion’s ecological and social assets are needed: its geology and topography; its soils and watersheds; its agriculture and biodiversity. The collaborative monitoring of living systems needs to be designed – together with feedback channels. New service platforms are needed to help people to share resources of all kinds – from land, to time. Novel forms of governance must also be designed to enable collaboration among diverse groups of people.

None of these actions means designers acting alone; their role is as much connective, as creative. But in creating objects of shared value – such as an atlas, a plan, or a meeting – the design process can be a powerful way to foster collaboration among geographers, ecologists, economists, planners, social historians, writers, artists and other citizens.

One way to begin the journey towards the establishment of a hub, or learning centre, could be a Doors of Perception Xskool.These encounters bring local actors together to ask: What are the key social-ecological systems in this place? What are the opportunities for this city-region? How night one design in them? How does one get started? The outcomes of an xskool, typically, include a shared perception of new opportunities; new connections between motivated and effective people; and the determination to make something happen.

Note: Up to ten residencies are available at our summer xskool in Sweden in August. If you are involved in a bioregional scale project, this would be one good moment to come and help develop this agenda.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]