We can do this the hard way or the easy way. The easy way is that you skip this post and buy the book now.

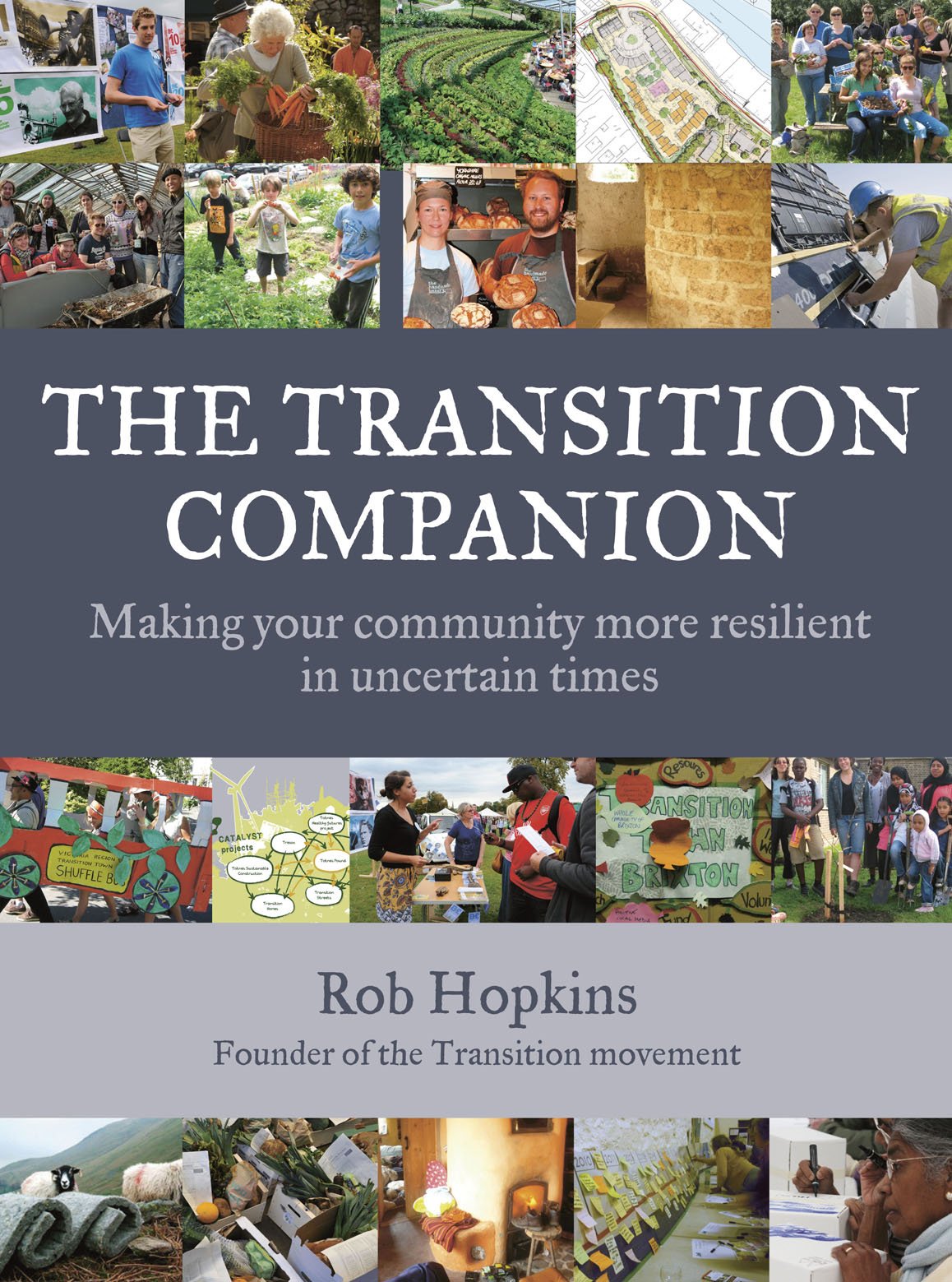

The hard way is that your reviewer attempts to describe a 320 page book whose contents have been shaped by the infinitely varied experiences of self-organising initiatives around the world. In these, thousands of people have explored one question over a five year period: “How do we make our community more resilient in uncertain times?”.

One of the many virtues of this awesome and joysome book is that the word “strategic” does not appear until page 272; a section on “policies” has to wait until page 281. It’s not that the book is hostile to high altitude thinking; on the contrary, its pages are scattered with philosophical asides on everything from Buddhist thinking and backcasting, to time banking and thermodynamics. But the rational and the abstract are given their proper, modest, place.

The book is filled with incredibly handy short texts about issues that confuse many of us. What, for example, are we to think of Community Supported Agriculture? Is it enough to sign up to a vegetable box scheme – and find the resulting service inflexible and irritating? Maybe yes and maybe no, writes Hopkins. For him, our relationship with the people who grow our food should be shaped by four key principles (page 268): “shared risk; transparency; community benefits; and building resilience”. Within that framework, the details are down to us.

There’s also an especially handy chart (page 253) about new career opportunities in a more localised economy. A wondrous array of new job titles ranges from hedgerow drink maker to compost manager – alongside more recognisable green jobs.

Another plus: The book will start more arguments than it resolves. One could run a summer school on the single chart (page 48) that asks: “What does ‘localisation’ mean?” It doesn’t mean self-sufficiency, writes Hopkinson, but it does mean “increased meeting of local needs through local production where possible (especially for food, energy and construction”. This will not please agribusiness, nor the the Real Estate Industrial Complex – but is otherwise uncontroversial. I also like the idea that “localisation does not mean insular communities” but does mean “a global network of communities organising their economies but sharing their experiences and advice…a global process of resilience-building in a range of settings”.

Other assertions in the chart are harder to swallow. For example, localization “does not mean the driving out of multinational businesses and other employers” and does mean “there may well be situations where collaborations with existing multinationals may be a skillful approach”. Well, maybe. Raging at multinationals may well be bad tactics, and a waste of energy, but the fact remains that MNCs are pre-programmed to grow to infinity in a finite world, and their CEOs are legally obliged, as well as incentivised, to follow an ecocidal path. How to do it may be hard – but they have to go.

Lower down that page is another provocation: “localization does not mean a population forced to toil in the fields” but does mean “finding new models for land access”. The trouble here is that the people most actively exploring “what land management might look like if based on an understanding of peak oil and cimate change” are hedge funds; they’ve bought 35m hectares of food producing land in poor countries in recent years. http://bit.ly/xvNVhF Transition’s enthusiasm for “learned optimism”, on these occasions, feels inadequate.

Such provocations are spice that liven the book up. Its greatest achievement is to document living examples of what systems thinking applied in everyday life can be like. Hopkins quotes Donella Meadows: “the sustainability revolution will be organic. It will arise from the visions, insights, experiences and actions of billions of people”.

As a movement, Transitiondoes not aspire to be wholly without structure. Two among those billions of people sent Hopkins and his tiny team in Totnes terrific suggestions for how Transition is (or should be) organized. Joanne Porouyow, of Transition Los Angeles, proposes the ‘ubbelliferae’ model, like the flowers of a fennel plant (below)

“Almost out of sight, a strong structure keeps the flowers supported, fed, and connected”. Scott McKeown of Transition Sebastopol, thinks of Transition as mycelium, a fine fungus that runs though undisturbed spoils ls in networks. The book is filled with such enchanting and insightful asides.

May copy of the book arrived with the CD of a new film, ‘In Transition 2.0’ which I hope to review shortly.

Some earlier Doors of Perception posts on Transition are here and here and here