Doing good is a feel-good activity – but a warning: Around the world, the most brutal excesses of development are also fuelled by design ‘visions’. I’ve learned, after 35 years as a guest in their communities, that we often have more to learn from smart poor people – on things like ecology, low-energy lifestyles, or caring for our elders – than they have to learn from us. With that caveat in mind, here are some Rules of Engagement to govern design-aid expeditions.

Rule one: Look near as well as far. There’s a lot of work to be done nearby as well as far away. It’s easier to enhance the human resources, culture, heritage, traditions, know-how and skills of a local culture, than that of a distant one.

Rule two: Work for actual people, not for categories. Be on your guard whenever you read the words ‘the poor’ (or ‘the elderly’ or ‘the blind’ or ‘the disabled’). These casual (and widespread) habits of language disembody and dehumanise people. (If you don’t believe me, ask a blind person).

Rule three: Respect what’s already there. Designers are trained to to change things, when sometimes the best course is to leave well alone. The good news is that visiting designers can act like mirrors, reflecting positive things about a situation that local people no longer notice or value.

Rule four: Empower local people. Any design action that rearranges places and relationships is an exercise of power. A good test for the sensitivity of incoming designers is whether they enable people to increase control over their own territory and resources.

Rule five: Commit long-term. When Sergio Palleroni offered the support of design students to communities in New Orleans, he commited to a minimum of three year’s engagement. It takes time to understand a situation, time to listen to local people and gain their trust, time for appropriate solutions to emerge.

Rule six: Small is not small. Small design actions can have big consequences, many of them, but not all, positive ones. If someone builds a bus stop in an urban slum, a vibrant community can sprout and grow around it. Such is the power of small interventions into complex urban situations. Read Small Change, by Nabeel Hamdi for more inspiring examples of the power of thinking small.

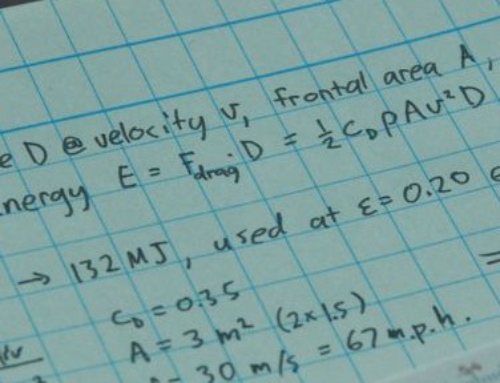

Rule seven: Think whole systems. Paul Polak reckons the design and technology of a device – such as a pump, or sprinkler system – is not much more than ten percent of the complete solution. The other ninety percent involves distribution, training, maintenance and service arrangements, partnership and business models.

Rule eight: Hands-on or hands-off: Hungry people need posters and campaigns less than they need food to eat.

FURTHER READING

Other talks and texts by me on ‘development’

World Social Forum: Another World is Possible

To Hell With Good Intentions, by Ivan Illich

The White Savior Industrial Complex, by Teju Cole