An interview with Jonny Gordon-Farleigh, the editor and publisher of STIR magazine. Current and back issues of the magazine are available in the online shop

Jonny Gordon-Farleigh: Your new book, How to Thrive in the Next Economy, explores practical innovations in sustainability across the world. What stories would you pick out as the most instructive for the scale of change we need to see?

John Thackara: The sheer variety of projects and initiatives out there is, for me, the main story. No single project is the magic acorn that will grow into a mighty oak tree. We need to think more like a forest than a single tree! If you look at healthy forests, they are extremely diverse—and we’re seeing a healthy level of diversity in social innovation all over the world. Many people say we need to focus on solutions that scale, but to me that’s globalisation-thinking wearing a green coat. Every social and ecological context is unique, and the answers we seek will be based on an infinity of local needs.

JGF: What examples of inspiring stories can you give?

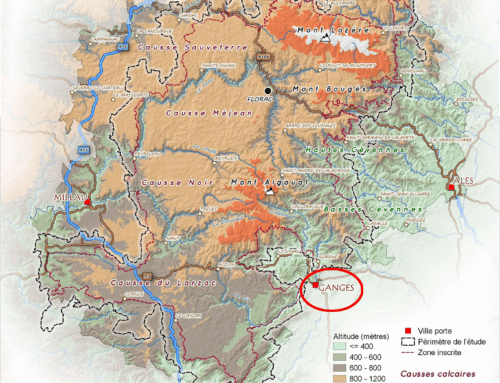

JT: The story of soil has been an epiphany for me. Soil is the largest living system on the planet; without it, we wouldn’t exist. But I only learned this a few years ago. At first I read a whole pile of articles and books, but it all came to life when I then went on a soil creation course in the Cévennes, the mountainous area in France where I live. Our teacher was a French agro-ecologist Robert Morez who has worked as an agricultural advisor in Africa for forty years. He showed us how to make a growing mound with a bunch of ingredients: bone meal, dried blood, crushed oyster shells, wood fire ash, onto a growing mound of wood, twigs, leaves, straw. Each layer is seasoned, as if with salt and pepper, by this powdery mix of minerals and biological activators. Robert told us we were learning “how to construct a bio-intensive planting mound”—but in my mind, I was making soil, rather than depleting it, for first time in my life.

JGF: There was a figure recently stating that we have around 100 harvests left.

JT: Yes, that figure was for British soil at the current rate of soil depletion. Other reports suggest that we are losing 3.5 tonnes of soil for every person on the planet every year. The numbers are either hard to grasp or just dispiriting, but either way, it’s enormous. But what I learned up the mountain is that we can restore soil because people in different regions of the world have been doing precisely that for a long time. On its own, soil formation is an extremely slow process— sometimes taking thousands of years—but a growing band of visionaries have discovered that the process can be speeded up dramatically if the right approach is followed.

JGF: Farming organisations, such as La Via Campesina, describe this approach as agroecology.

JT: Yes, they do. It’s an ugly word, I know, but it describes the practical wisdom of people who’ve been stewarding the land for generations. It’s not my job to tell La Via Campesina what language to use—the word make sense to their 300,000 members—but I think one of the things that we writers can do is come up with better words!

JGF: This leads into my next question: Early on in the book you remind readers to be careful of the words we choose to make sense of these new times. Noting, “one man’s energy descent, is another woman’s energy transition.” Words that I find unhelpful, and come to mind, are phrases such as ‘degrowth’. What language do you find alienating in the language around the new economy?

JT: I’m totally not a fan of ‘degrowth’. I’ve learned through experience that calling for people to give things up, voluntarily or otherwise, doesn’t work. Most people simply turn off when confronted by lists of prohibitions. I try, instead, to talk about the kinds of growth we do need: land getting healthier, water getting fresher, air cleaner to breathe, communities more resilient. These kinds of growth add up to new kind of value.

JGF: You also write about healing the metabolic rift, a term that Karl Marx used to describe the loss of interdependency between social and ecological systems and the reason for recurring crises.

JT: The metabolic rift is another of the ugly green buzzwords that seem to plague us—but learning about the concept was another lightbulb-going-off-in-my-head moment. I’d spent half my life trying to figure out why even decent people who love animals and children persist in organising the world in such an obviously damaging way. An answer that makes sense is that we don’t experience the result of the damage that we do as visceral, embodied feedback. We don’t feel the pain felt by the earth because it happens somewhere else—out of sight and therefore out of mind.

JGF: Could you explain more about what the metabolic rift is?

JT: It’s not that our brains lack processing capacity—more, that they’re preoccupied by the wrong inputs. A combination of paved surfaces and pervasive media has shielded us from direct experience. Material progress itself has distracted us from the health of the natural living systems upon which we still depend—and, indeed, are a part. If you put it to someone—as I have done—that, without soil, humanity will quickly starve, they usually agree, nod sagely—and wait for me to change the subject. Few of the city-dwelling people I know ever touch, feel, taste or smell the stuff—healthy or otherwise. Our children are not taught about it at school. It’s the same with climate change, the loss of biodiversity, deforestation; or dying seas: Out of sight, out of mind. Why would we care?

The ways we understand the world are shaped by the political and economic system. As Jason Moore explains in his book Capitalism in the Web Of Life, the metabolic rift is not a regrettable side-effect of the modern economy; it’s written into its DNA. Our present economy has to grow in order to survive, and ceaseless growth entails ever-larger inputs of external resources and energy. Our problems started when we first travelled across the world to take other people’s minerals and resources—and that was 500 years ago. This is where the richness of the so called developed nations originates. The Spanish plundered wood from the Baltic region to build the ships in which they sailed off to the West Indies to bring back spices, and so on. A hundred million kilos of silver from Latin America provided much of the capital for Europe’s industrial revolution. Our bad behaviour dates back a long way!

JGF: Your book suggests that organising the world around bioregions is one way to close the metabolic rift?

JT: The notion of a bioregion appeals to me for a specific reason: Telling city people to take better care of nature has been one of my many failures as a writer. Intellectually, city folk buy the argument that growth should mean soils, biodiversity and watersheds getting healthier, and communities more resilient. But in the absence of positive feedback from some distant place called Nature, people just don’t connect with my exhortations. I realised that a more compelling story, and a shared purpose, were needed. So I started asking people two questions: “Does your city know where its lunch is coming from? And is that place healthy—or not?”

With the prospect of missing lunch as motivation, I’m finding that the idea of a bioregion is an appealing way for city people to reconnect with living systems, and each other, through the unique places where we live. It acknowledges that we live among watersheds, foodsheds, fibresheds, and food systems—not just in cities, towns, or ‘the countryside’. The idea is culturally dynamic, too—far more than abstract words like sustainability, or resilience, or transition. A bioregion is about unique geographic, climatic, hydrological and ecological qualities. These can be the basis for meaning and identity, and people get that.

But beyond the idea in general, what most turns people on—especially designers and artists—is the sheer variety of work to be done in bringing a bioregion to life. Maps of a bioregion’s ecological assets are needed: its geology and topography; its soils and watersheds; its agriculture and biodiversity. The collaborative monitoring of living systems, the interactions among them, and the carrying capacity of the land, needs to be designed—together with feedback channels. Spaces and places that support collaboration need to be identified and, where needed, adapted—from maker spaces to churches, from town halls, to libraries. New collaboration and peer-to-peer platforms are needed to help people to share resources of all kinds—from land, to time and knowledge. New economic and business models need to be adapted and deployed, such as peer production, commons economics, and open value accounting. Novel forms of governance and discussion must also be designed that enable collaboration among diverse groups of people and enterprises. Every bioregion will need its own identity, too—what the bioregion looks like, and feels like, to its citizens and visitors.

JGF: Those subjects are pretty broad-ranging. Are you suggesting that designers and artists are best-placed to take care of them all?

JT: None of these actions mean designers or artists are acting alone. Developing the agenda for a bioregion involves a wide range of skills and capabilities: The geographer’s knowledge of mapping; the conservation biologist’s expertise in biodiversity and habitats; the ecologist’s literacy in ecosystems; the economist’s ability to measure flows and leakage of money and resources. But in creating objects of shared value—such as an atlas, a website, a plan, a building, a landscape, or a meeting—I do think the design process can be a powerful way to foster collaboration among diverse disciplines and constituencies, yes. I’d also say that the service designer can bring something special to the creation of platforms that enables actors to share and collaborate. And—as you’ve shown so wonderfully in STIR magazine already—artists have a unique capacity to represent real-world phenomena in ways that change our perceptions.

GF: At the recent New Economy Summit we both attended in Bristol, I mentioned Charles Eisenstein’s claim that, “the city of New York, with over one million people, met all its food needs from within seven miles prior to 1850.” If you look at the scale of most UK cities, such as Bristol or Manchester, it’s a very possible project.

JT: It is very doable. Urban farming started off as a minority fad, but it’s quickly going mainstream in many northern cities. A lot of smart innovation to support urban farming is happening—but it’s not much about high-tech control systems. It’s more about new ways to share resources, and collaborate to get the work done. New kinds of enterprise are emerging: food co-ops, collective kitchens, community dining, edible gardens, new distribution platforms. The big change is an understanding that urban farming can encompass an archipelago of growing spaces within a 50-mile radius—a mosaic of growing situations that we can think about as a whole.

JGF: What examples could you give of urban projects that you experienced while writing the book?

JT: I’m very excited by a project called The Food Commons in the USA. This project marks a radical shift from a narrow focus on the production of food, towards a whole systems approach in which the interests of farm communities, the land, watersheds, and biodiversity, are all considered together as inter-dependent parts. The Food Commons is conceived as a kind of connective tissue that weaves connections between grassroots projects, on the one hand, and vital support services, on the other: legal, financial, communications and organisational.

Another great example is the city of Cleveland, also in America. It’s a classic rustbelt city that has lost large chunks of traditional industries. They have a particularly down-to-earth mayor who, when badgered by activists for the need for more urban farms, commissioned a three-year a peer-reviewed assessment of what could be grown on different patches around the city repurposed for growing food, such as abandoned lots, vacant buildings. The results surprised everyone. Something like 70% of all fruit and vegetables, and quite a big chunk of the dairy products, could be grown within Cleveland’s city limits. And that is without even venturing 20 miles outside the city. So now the Cleveland model, as it’s called, is almost a reincarnation of the new city model from the 1920s.

JGF: One of the big shifts you advocate in the book is to move beyond the language of ‘do less harm’ to the idea of ‘leaving things better.’ What inspired this change of approach in both thought and action?

JT: I had another transformational experience at a meeting of 200 sustainability managers at a famous home furnishings giant in Sweden. During 20 years of uninterrupted work on sustainability, they told me, this famous company has made thousands of rigorously-tested improvements that are recorded on what they call a “list without end.” The range of improvements I heard about was startling—even admirable—except for one fact: The one thing this huge company has not done is question whether it should grow. On the contrary: It is committed to double in size by 2020. By that date, the number of customers visiting their giant sheds will increase from 650 million a year at the time of writing to 1.5 billion a year. Sitting there, it hit me that there’s a problem with this narrative that concerns wood. The company, as the third largest user of wood in the world, has promised that by 2017 half of all the wood it uses—up from 17% now—will either be recycled, or come from forests that are responsibly managed. Now 50% is a vast improvement, but it also begs the question: What about the second half of all that wood? As the company doubles in size, that second pile of wood—the un-certified half, the unreliably-sourced-at-best half—will soon be twice as big as all the wood it uses today. The impact on the world’s forests, of one company’s ravenous hunger for resources, will be catastrophic. The committed and gifted people I met in Sweden—along with sustainability teams in hundreds of the world’s major companies—are confronted by an awful dilemma: however hard they work, however many innovations they come up with, the net negative impact of their firm’s activities on the world’s living systems will be greater in the years ahead than it is today. And all because of compound growth. This was the moment when I realised that it doesn’t matter how committed you are to doing less harm. If it is simultaneously committed to grow then they will inevitably leave things worse.

JGF: Throughout the book you look at ‘nonmarket work,’ life ‘without money,’ and the ‘commons of care,’ or what is sometimes known as the shadow economy. Commons advocate David Bollier claims “an estimated two billion people depend on various natural resource commons for their everyday survival—farmland, fisheries, forests, irrigation water, wild game.” And this figure dramatically increases when you add care and other forms of noneconomic activity. How much of a role can commons play in western economies, alongside co-operatives, social enterprises and other social business models?

JT: A gigantic amount. The commons is an idea, and a practice, that generates meaning and hope. I’m nervous of definitions—they cause endless disputes and also tend to freeze an idea in time —but I like the way Silke Helfrich talks about the commons as “all the things that we inherit from past generations that enable our livelihoods.” Seen through that lens, the commons can include land, watersheds, biodiversity, common knowledge, software, skills, or public buildings and spaces. The important thing is that the commons are a form of wealth that a community looks after, through the generations. The idea embodies a commitment to ‘leave things better’ rather than extract value from them as quickly as possible. They are the opposite of the impulse to monetise everything. And because the commons, as an idea, affirms our codependency with living systems and the biosphere, it also represents the new politics we’ve all been looking for to replace the industrial growth economy we have now.

None of this is new, by the way. The commons goes back an awfully long way. It describes the way communities managed shared land in Medieval Europe. Even earlier history, too, is filled with examples of communities managing common resources sustainably. Examples of water being shared as a commons date back 8,000 years. One of the things I’ve learned from the so-called undeveloped world is that the care-based economy has existed throughout human history—looking after each other, and the land, in a multitude of ways, many of which don’t involve paid-for work.

Writers like Hazel Henderson have been trying to refocus our attention on the care economy, writing 30 to 40 years ago. More recently, an important Swiss writer called Ina Praetorius has argued for a care-centered economy. In German the word care encompasses being mindful, looking after, attending to needs, and being considerate—caring for the world, in other words, and not only nursing and social-work activities or housework in the narrow sense. In a care-centered economy, the commonly held resources that enable us to look after each other, and nature, are part of the same story.

Theodore Shanin, who has been called the peasant’s philosopher, makes a similar point: in terms of the land, the water and the air, so called peasants, farmers and poor people have been stewards of their commons for generations; modern, industrialised mass-production farming made it harder and harder to do their job. The care economy has always existed, and we now have the pleasant task to reinvent it for these new times.

JGF: The word ‘connection’ crops up a lot in the book. Is that a core theme?

JT: Too true, it is. I’m like an amateur EM Forster: Howard’s End opens with the words, “Only connect.” The word unlocks so many blockages. I’ve learned that too many of our most celebrated inventions have been the result of a design approach that strives for perfect, static, utopian solutions. These are different, in kind, from real-world ecologies that are dynamic and constantly changing. This habit of mind of ours is not limited to the engineering of hard systems; some visions of nature itself have been utopian in this sense.

Until recently, conservation research tended to focus on the individual species as the unit of study—for example, by looking at the impact of habitat destruction on an individual’s situation. I’m especially inspired by the work of the ecologist Jane Memmott. She has explained that species interactions may be much more important. All organisms are linked to at least one other species in a variety of critical ways—for example, as predators or prey, or as pollinators or seed dispersers—with the result that each species is embedded in a complex network of interactions. The extinction of one species can lead to a cascade of secondary extinctions in ecological networks in ways that we are only just beginning to understand.

The eco-philosopher Joanna Macy is another inspiration. She describes the appearance of this new story as the ‘Great Turning’, a profound shift in our perception, a reawakening to the fact that we are not separate or apart from plants, animals, air, water, and the soils. There is a spiritual dimension to her story—Macy is a Buddhist scholar—but her Great Turning is consistent with recent scientific discoveries, too—the idea, as articulated by Stephan Harding, that the world is “far more animate than we ever dared suppose.” No organism is truly autonomous. In Gaia theory, systems thinking, and resilience science, researchers have shown that our planet is a web of interdependent ecosystems. From the study everything from sub-microscopic viruses, yeasts, ants, mosses, lichen, slime moulds and mycorrhizae, to trees, rivers and climate systems, this new story has emerged. All natural phenomena are connected. Their very essence is to be in relationship with other things—including us.