(Above: Debra Solomon examines nature’s internet at Schumacher College in England)

The Design Museum in London opens at its new home this week with, as its centrepiece, an exhibition called Fear and Love curated by Justin McGuirk. I contributed the following text to the book.

Why we need a new story

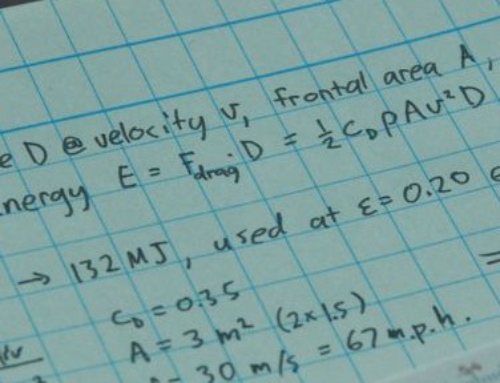

In 1971 a geologist called Earl Cook evaluated the amount of energy ‘captured from the environment’ in different economic systems. Cook discovered then that a modern city dweller needed about 230,000 kilocalories per day to keep body and soul together. This compared starkly to a hunter-gatherer, 10,000 years earlier, who needed about 5,000 kcal per day to get by.

That gap, between simple and complex lives, has widened at an accelerating rate since Cook’s pioneering work. Once all the systems, networks and equipment of modern life are factored in – the cars, planes, factories, buildings, infrastructure, heating, cooling, lighting, food, water, hospitals, the internet of things, cloud computing – well, a New Yorker or Londoner today ‘needs’ about sixty times more energy and resources per person than a hunter-gatherer – and her appetite is growing by the day.

To put it another way: modern citizens today use more energy and physical resources in a month than our great-grandparents used during their whole lifetime.

It’s a shame, in retrospect, that Earl Cook’s easily-grasped comparison was overshadowed by the publication of Limits to Growth a year later. That book, based on a computer model at MIT, warned of environmental ‘overshoot and collapse’ if the perpetual growth economy continued unchecked.

The apocalyptic story in Limits generated plenty of fear – but it was also demoralising.

In the 45-year stream of films, books, and campaigns that followed its publication, the enormity of the challenges facing he planet contrasted starkly with the tiny actions proposed as a response.

Two simple examples: We were exhorted to take our shopping home in a reused plastic bag, and to feel good about doing so – only to be told later that the bag is responsible for about one-thousandth of the environmental footprint of the food it contains.

In the same spirit of every little helps, we were urged to turn off our phone chargers at night – and then it emerged that the energy thus saved was equivalent to driving a car for one second.

In retrospect, our design focus on messages and things distracted attention from the system behind the thing – the societal values, and economic structures, that shaped our behaviour in the first place. We committed to “do less harm” within a system that, because it must grow in order to survive, unavoidably does more harm as it does so.

This lesser-of-two evils approach has also compromised one of the alternative words to sustainability being proposed, resilience. Described by one commentator as “the ability to take a punch”, resilience planning has resolutely evaded an obvious question: “why did that guy – or system – punch you in the first place?”

The answer is an economic system whose core purpose is to produce, produce produce, and grow grow grow.

Signals of transformation

The good news is that, around the world, grassroots projects are proliferating that are shaped by a different logic. This global movement contains a million active groups – and rising.

Its ranks include energy angels, wind wizards, and watershed managers. There are bio-regional planners, ecological historians, and citizen foresters.

Alongside dam removers, river restorers, and rain harvesters, there are urban farmers, seed bankers, and master conservers. There are building dismantlers, office-block refurbishers, and barn raisers.

There are natural painters, and green plumbers. There are trailer-park renewers, and land-share brokers.

Their number includes FabLabs, hacker spaces, and the maker movement. The movement involves computer recyclers, hardware re-mixers, and textile upcyclers. It extends to local currency designers. There are community doctors. And elder carers. And ecological teachers.

Few of these groups are fighting directly for political power, or standing for election. They cluster, instead, under names like Transition Towns, Shareable, Peer to Peer, Open Source, Degrowth, Slow Food, Seed Freedom, or Buen Vivir.

These edge projects and networks, when you add them together, replace the fear that has so hampered the environmental movement with a story of love – a joyful new story about our place in the world.

In contrast to a global economy that degrades the land, biodiversity, and the people it touches, these projects signal a growing recognition that our lives are codependent with the plants, animals, air, water, and soils that surround us.

The philosopher Joanna Macy describes the appearance of this new story as the ‘Great Turning’ – and her voice is just one among many.

The Pope’s recent encyclical Laudato Si, for example, promotes the concept of ‘integral ecology’ – a reconnection between man and nature – to 1.2 billion readers.

The Pope’s transformational story has been echoed by the leaders of more than one billion Muslims, a billion Hindus, a billion Confucians, and 500 million Buddhists. The readership of these teachings adds up to 75 per cent of world’s population.

Of course, if everyone did what they were told by religious leaders, there’d be no sin in the world – and we’re not there yet. But a paradigm shift in science is adding secular credibility to this new story.

In studies at multiple scales – from sub-microscopic viruses, and slime molds, to trees and climate systems, the story is consistent: The essence of plants, animals, air, water, and the soils is to be in relationship with other life forms —including us.

A single teaspoon of garden soil, it;’s been shown, may contain thousands of species, a billion individuals, and one hundred metres of fungal networks – and this hidden world does not stop there.

Microbiology permeates other ecosystems, too – including our own bodies. As in the soil, so too in our stomachs, bacteria break down organic matter into absorbable nutrients. In the case of plants, nutrients are made available to through their vast surface area of root systems in the topsoil and rhizosphere.

For Patrick Holden, the healthy topsoil, thriving with microorganisms, which covers much of the land’s surface, is in effect the “collective stomach of all plants”.

Every action we take – from feeding soil bacteria and fungi with composts or manures, to the timing of grazing and cultivation – can enhance or diminish soil life.

And because microbial processes are inter-connnected, the health of the soil, and our own heath, are part of a single story, too.

From parts, to wholes

It’s one thing for Popes and soil scientists to tell us to care for living systems – but is asking city dwellers to empathise with earthworms too big an ask? Fewer than half of us ever see or touch soil, after all.

For long time, I harboured just those misgivings – until I had an epiphany on an island in Sweden.

Fifty designers, artists and architects, gathered together for a summer workshop, were asked to explore two questions: What does this island’s food system taste like? and, How does this forest think?

My concern that living soil would not engage designers proved unfounded. It was like pushing at an open door:

Having scrabbled around the forest of Grinda like so many voles, they then staged a Soil Tasting Ceremony in which infusions from ten different berries on the island were displayed in wine glasses next to soil samples taken from each plant’s location. We were then invited to compare the tastes of the teas and soils in silence. It was a powerful moment.

Systems thinking, it seems, becomes truly transformational when combined with systems feeling – which is something we all crave.’ “We yearn for connection with one another, and with the soul,’ writes Alastair McIntosh, ‘but we forget that, like the earthworm, we too are an organism of the soil. We too need grounding”.

This lesson works surprisingly well in city design.

When this writer meets with city planners or managers, we always start with two questions: “Do you know where your next lunch will come from?” and, “Do you know if that place is healthy – or not?”

These questions help shift the design focus from the dry subject of public service delivery towards a whole-system concern with the health of places that keep the city fed and watered.

Within this frame, the health of farm communities, their land, watersheds, and biodiversity, become integral aspects of the city’s future prosperity, too.

A focus on living systems acknowledges that we live among watersheds, foodsheds, fibersheds, and food systems – not just in cities, towns, or ‘the countryside’.

With food, especially, the opaque subject of living systems finally makes sense.

The presence of good bread – and the microbial vitality bread making invokes – is an especially reliable indicator that a city’s food system is healthy.

In dozens of major cities, real bread pioneers are creating shorter grain chains by connecting together a multiutude of local actors in ways that reduce the distance between where grain is grown, and the bread consumed: urban farmers, seed bankers, food hubs, farmers markets, local mills and processing facilities.

In London, Brockwell Bake grows heritage wheat on allotments, in school and community gardens, and with farmers close to the city. As this lattice-work of activity, infrastructure, and skills connects up, regional ‘grain sheds’ are beginning to take shape.

New distribution platforms pay an especiay important role. La Ruche Qui Dit Oui for example – ‘The Hive that Says Yes’ – is the brainchild of a French industrial designer and chef, Guilhem Cheron. La Ruche combines the power of the internet with the energy of social networks to bridge the gap that now separates small-scale food producers from their customers.

When someone starts a local hive, she recruits neighbours, friends, and family to join – the ideal number seems to be thirty to fifty members – and the group then looks for local food producers to work with. These farmers offer their products online at a desired price, and hive members pay 20 per cent on top that to cover a fee for the hive coordinator, a service fee to La Ruche, plus taxes and banking costs.

La Ruche makes money as a platform provider, but it is not an intermediary: the farmer receives the price asked for, and the system is fully transparent; everyone involved knows what happens to every cent transacted.

In food platforms such as La Ruche, the focus is not just on production; they embody a whole systems approach in which the interests of farm communities and local people, the land, watersheds, and biodiversity, are considered together – with stewardship as a shared value.

A focus on food systems leads to a new design agenda for cities. New kinds of enterprise are needed: food co-ops, community kitchens, neighbourhood dining, edible gardens, food distribution platforms.

New sites of social creativity are needed: craft breweries, bake houses, productive gardens, cargo bike hubs, maker spaces, recycling centres, and the like. Business support is needed for platform co-ops that enable shelter, transportation, food, mobility, water, elder care to be provided collaboratively – and in which value is shared fairly with the people who make them valuable.

Technology has an important role to play as the infrastructure needed for these new social relationships to flourish; mobile devices and the internet of things are valuable to the extent that they make it easier for local groups to share equipment and common space, or manage trust in decentralised ways.

The most important technologies are more earthly than virtual – those to do with the restoration of soils, watersheds and damaged land. The ClimateTECHwiki lists 260 promising techniques –from beach nourishment, to urban forestry.

From soil to skin

Clothes, are another daily life necessity in which alternative forms of design and production are emerging.

Thanks to the tireless work of activists and researcherss, millions of people are now aware of the harm wrought by textiles and fashion as industrial systems – from energy and water use, to soil depletion, waste, and toxic outputs from materials manufacturing.

But athough the fashion industry – famously sensitive to consumer attitudes – has developed sophisticated ways to measure these social and environmental impacts, exhortations to ‘buy less, wash less’ have proved ineffective, on their own, in an economy whose financial DNA compels it to grow at all costs.

Not a single fashion brand has told its customers to buy less.

Chastened, but not defeated, the new approach is to grow alternative networks at the edges of the mainstream fashion system. In California, for example, a project called Fibershed links together the different actors and technical components of a bioregional ecosystem: animals, plants and people, skills, spinning wheels, knitting needles, floor looms.

For Fibershed’s founder Rebecca Burgess, the priority to integrate vertically – ‘rom soil to skin’.

By design, the health of soils is an integral part of this whole systems approach. Rather than constantly drive the land to yield more fiber per acre, Lynda Grose helps farmers match production to the capacities of the land whose health and carrying capacity is constantly monitored; in this way, decisions are made by the people who work the land and know it best, and fiber prices are based on yields the land can bear, and on revenues that assure security to the farmer.

‘Growth’ is measured in terms of land, soil, and water getting healthier, and communities more resilient.

A new story of place

The design world has innovated a raft of alternative methods and frameworks as replacements for industrial mass production; they have names like cradle-to-cradle, natural step, living buildings, resilience planning, biomimicry, the circular economy., the symbiotic economy.

Although welcome, these approaches are limited by a persistent bind-spot: They take the ‘needs of the present’’ – and the economic system that currently meets them – as their starting point, and proceed from there. (Brundtland Commission definition 1987).

Globalisation, in particular, distracted us from a fundamental design principle: complex phenomena cannot be isolated from their context – and no two places on the planet are the same.

As explained by Joel Glansberg, a pioneer of regenerative design, ecological systems, through the forces of their geology, hydrology, and biotic communities, organize themselves around certain identifiable patterns that are unique to each place.

Social and cultural systems are part of the same story. Woven over time through human settlement, they too are shaped by the ecology of the landscape.

If the regeneration of social and ecological assets cannot be practised remotely, our design focus needs to shift from things, to connections – especially the connections between people and natural systems in places which have a shared meaning and importance – such as the bioregion.

A bioregion maps the abstract concepts of sustainability, or a ‘living economy’, to the real world. ‘The economy’ becomes a place, and the urban landscape is re-imagined as an ecology with the potential to support us: the soils, trees, animals, landscapes, energy systems, water and energy sources on which all life depends.

A bioregional approach, which nurtures the health of the ecosystem as a whole, attends to flows, bio-corridors, and interactions – inside cities, as well as in the countryside. It thinks about metabolic cycles and the ‘capillarity’ of the metropolis wherein rivers and biocorridors are given pride of place.

A number of design tasks follow from this approach. Maps of a bioregion’s ecological assets are needed: its geology and topography; its soils and watersheds; its agriculture and biodiversity. The collaborative monitoring of living systems needs to be designed – from soil health to air quality – and ways found to observe the interactions among them, and create feedback channels.

Many of these tasks entail diverse disciplines collaborating together – with design as the ‘glue’ that holds them together.

The reconnection of cities to their bioregion – their ‘re-wilding’ – is not much about the creation of wide open spaces and new parks; it’s more about patchworks, mosaics, and archipelagos.

When parks were built in past centuries they were called the ‘green lungs’ of towns. Decades of over-development have put an end to those expansive days; this new approach is all about nurturing patches, some of them tiny, and linking them together.

There are cemeteries, watercourses, avenues, gardens, and yards to adapt. There are roadside verges, green roofs, and facades to plant. Sports fields, vacant lots, abandoned sites, and landfills can be repurposed.

Abandoned buildings and ruins, empty malls, and disused airports need to be adapted – not to mention the abandoned aircraft that, before too long, will be parked there.

In Vienna, the design firm Biotope City develops ‘micro green spaces’ that transform neighbourhoods. And in the Jaeren region of Norway whose landscape has been battered by the footprint of the oil economy, the architect Knut Erik Dahl teaches young designers to look for and appreciate the tiniest examples of biological life in among the people, goods, and buildings: solitary plants, rare lichen, rare insects. It’s low-cost, hands-on work. They call it ‘dirty sustainability’.

In a project called Dartia, a coalition of statutory organisations and local people are stewarding the Dart Valley bioregion in South Devon. Based on a detaied scientific analysis of the river’s social and ecological assets by the West Country Rivers Trust, Dartia coordinates diverse physical activities such as the repair of river banks; monitoring what’s being put down drains; and the creation of rain gardens that use storm water run-off.

The health soils near the river, and flora and fauna, are monitored. Drinking water purification stations are being established. Access access to the water is being improved for kayaks, and restricted for cows. A wondrous variety of rivershed stakeholders are working together: a large estate; farms; a water treatment plant; a plant nursery; a pub; a supermarket; a restaurant; a school; house and boat owners; a dock, and more. The Guild helps the region’s citizens see Dartia through new eyes and generate new ways to realise its contribution to a local living economy.

A care economy

In the new economy that’s now emerging care – for the wellbeing of social and ecological systems – replaces money as the ultimate measure of value.

Growth, in this care economy, takes on new meaning as the improved health of soils, plants, animals – and people. And because the health of all living beings is the property of unique social and ecological context, the innovation we do is necessarily situated.

Money will not disappear as this new economy unfolds – but it will only part of the picture. in the care-based economy that’s existed throughout human history, relatively few of the ways we’ve looked after each other, and the land, involved paid-for work; trust between people, commoning, and shared ownership, and networked models of care, were just as important – and will be again.

The notion of a care economy can sound poetic, but vague. Where, you may ask, is its manifesto? Who is in charge?

These are old-fashioned questions. The account given by Joanna Macy – of a quietly unfolding transformation – is consistent with the way scientists, too, explain how complex systems change.

By their account, a variety of changes, interventions, disruptions, and oppositions accumulate across time until the system reaches a tipping point: then, at a moment that cannot be predicted, a small release of energy triggers a much larger release, or phase shift, and the system as a whole transforms.

This between-two-worlds period of history contains myriad details of an emerging economy in which the very word ‘development’ takes on a profoundly different meaning.

Its core value is stewardship, rather than extraction. It is motivated by concern for future generations, not by what ‘the market’ needs in the next months. It cherishes qualities found in the natural world, thanks to millions of years of natural evolution. It also respects social practices – some of them very old ones – learned by other societies and in other times.

This new kind of development is not backwards looking; it embraces technological innovations, too – but with a different mental model of what they should be used for.

With every action we take, however small – each one a new way to feed, shelter, and heal ourselves, in partnership with living systems – the easier it becomes. Another world is not just possible. It is happening, now.

The above text is published in Fear and Love. It edited by Justin McGuirk to accompany his major exhibition at the Design Museum whose new home opens in Kensington, London, this week.