It’s hard not to be impressed by the Millau Viaduct that’s down the road from where I live in France.

The tallest bridge in the world boasts an eight-span steel roadway, is supported supported by seven huge concrete pylons, and weighs 36,000 tonnes.

But consider this: The great pyramid in Egypt weighs 180 times more than the Millau viaduct – and what happened to the folk who built that?

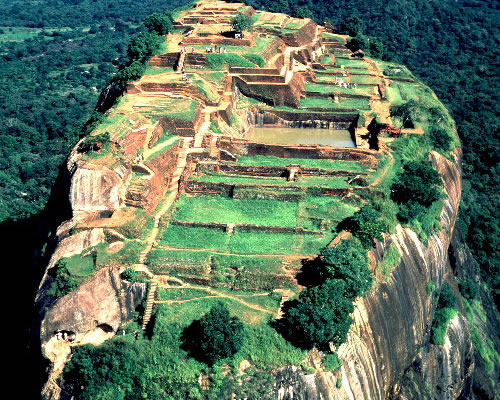

Sigiriya built [in what is now called Sri Lanka] in the fifth century, is equally impressive. Its system of man-made pools and water course incorporate incredibly sophisticated hydraulic technologies.

An interconnection of macro- and micro-hydraulics provided for domestic horticultural and agricultural needs, surface drainage and erosion control, ornamental and recreational water courses, and retaining structures and also cooling systems. Many of the fountains still are working.

The main difference between the old installations, and the Millau one, is that the pyramid and Sigiriya were built using mainly slave labour to shift an enormous mass of stone, while the French one is made of high performance materials whose manufacture consumed vast amounts of fossil-fuel derived energy.

The Millau Viaduct is a tourist attaction in the making. Future vistors will gawk at it and wonder: ‘how *did* they build that? and, ‘whatever *did* happen to that civilization?’.

In the absence of slave labour, and of cheap energy, neither the brilliant ancient infrastructures, nor the brilliant modern one, are models for the ‘green infrastructure’ that we need to build now.

A somewhat better model can be found right next to the Millau viaduct in the terraced landscapes of the Cévennes biosphere reserve.

Centuries ago, local people learned how to make use of their steep mountain slopes, poor soil, and a climate that swings from drought to heavy rains. Generations of peasants worked hard to prevent streams developing by breaking up the slopes into terraces to stop precious soil being washed away.

But most people live in cities or in their attenuated suburbs, not in biosphere reserves. What does green infra mean for them?

A wonderful small book published in Arizona answers that question. ‘Green Infrastructure for Southwestern Neighborhoods’ edited by Lisa Shipek and Catlow Shipek,explains the why, what, how and who of green infrastructure – retrofittable everywhere.

For the founders of the Watershed Management Group [WMG] green infrastructure (GI) refers to ‘constructed features that use living, natural systems to provide environmental services, such as capturing, cleaning and infiltrating stormwater; creating wildlife habitat; shading and cooling streets and buildings; and calming traffic’.

The WMG manual is aimed community and neighborhood leaders – and for good reason: they are the ones who will mobilise the human resources to get this kind GI built.