The Ecological Economy is now: Five Design Hotspots

The following text is my keynote talk at last week’s World Design Cities Conference (WDCC25) in Shanghai. At that same event I was astonished – and delighted – to be awarded the Frontier Design Prize (linkedin.com/thackara_i-was-given-the-frontier-design-prize-by-activity). This talk (video below) is a fair summary of the work being recognised by that award.

Shanghai, September 2025

Introduction

Our theme at this conference covers a lot of ground: “From Green Design, to Ecological Design”. It builds on the DesignS Manifesto we signed on this stage last year: sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii

I will come to that big picture story, but my main focus today will be on a pragmatic question. It’s one that I know concerns many of students and professional colleagues sitting here today. “Ecological Design: sounds nice – but guess what: I need a job”.

Or, If you’re from a company, or city hall, you’ll probably be thinking: “ Ecological Design. Those are pleasing words. But what do they have to do with growing my business, and our city?”

Please judge this talk by the degree to which I address those questions!

To begin, I need begin with a few words about the context of our back story – the transition from green design, to ecological design.

Green design, at its heart, has always meant “do less harm”. And we’ve tried diverse ways to do less harm over the last 60 years.

“Minimize environmental impact”. “Reduce waste”. “Reuse resources”. “Recycle products” .“ Green growth” . “Regenerative …’ – well, right now everything seems to be regenerative…

Over those “do less harm years”, and as public demand for action grew, many big companies responded – to a degree.

They invented a bunch Key Performance Indicators so they could measure progress: Net Zero; Cradle-to-Cradle; Circular Economy; Carbon Offsetting; Green Finance.

Those KPIs, in turn, spawned a multi-billion dollar consulting industry. Consultants designed an array of sustainability metrics, and then made more money in the business of sustainability reporting.

Biodiversity and carbon offsetting, were an especially clever bait-and-switch trick. Here’s how it worked. The bait? Investors were enticed by evocative images of an ecosystem getting healthier – which is great. The switch? Somewhere *else* in the world – off-camera – a company continued to burn carbon and/or destroy #biodiversity – secure in the knowledge that its activities have been ‘offset’. That’s it.

But all this “do less harm” activity distracted our attention from a problem. We were doing less harm inside an extractive and energy-intense economy that, over all, was growing exponentially.

People called it the Great Acceleration. The Great Acceleration was propelled upwards by a rocket fuel of intensive energy use, material extraction, and debt.

So I conclude my introduction with a painful reality check. Despite our good intentions, and intense efforts, the result of “doing less harm” – in an economy growing exponentially – is that more harm is being done to the planet, today, than when we started.

So that’s why green design – “do less harm” design – could never be our final destination.

It’s best thought of as a warm-up period leading to a more profound transformation that’s already under way.

This new economy is based on these simple statements:

- When our places get healthier, so do we;

- The health of people, and place, are a higher form of value than money,

or GDP; - Caring for place creates value.

It’s taking us a while for us to absorb the consequences of ecological design. But let’s not beat up ourselves too much. When Copernicus announced that earth revolves around the sun, and not the other way round, it took our cultures, schools and institutions another 100 years to adapt.

So that’s my introduction. I’ll now tell you about activities in four branches of an ecological economy that already involve substantial design inputs, and will soon need many more.

Ecological restoration

Ecological restoration, also known as earth care, involves a wide array of activities: watershed restoration, tree planting, soil repair, and other projects in which our environment – our lifeworlds – are being repaired in practical, hand-on ways.

In rich countries, at least, ecological restoration now provides more jobs than mining, logging, or steel production combined – all while improving the heath of the environment, instead of destroying it.

ecosystemmarketplace.com/ecological-restoration-25-billion-industry-generates-220000-jobs/

Millions more people around the world do this kind of work as volunteers. There’s a vast Pro-Am army out there that cares for its places – and rivers, and watersheds, and oceans – in practice.

A lot of this work is unknown to the broader public, and to most designers. Here in China, for example, an astonishing 3,700 wetland restoration projects have added over one million hectares of wetlands since 2012. New laws have been passed to protect wetlands, swamps and mangroves. More than two thousand nature reserves, and nine hundred national wetland parks, have been established. news.cgtn.com/26th-World-Wetlands-Day-What-China-has-done-for-wetland-conservation

Few of these projects advertise for “designers”, by that name, it’s true. But most restoration budgets include a requirement to create services, jobs, and livelihoods – the kinds of work that social innovation designers have been doing for years – at least in cities.

Community-based ecotourism, and education, are familiar urban-rural examples. But, as we discovered in the Urban-Rural festival in 2019 (slideshare.net/slideshow/urbanrural-exhibition-shanghai), dozens more jobs are emerging from the ground up.

New jobs in the textile sector, wellness tourism, and cultural services, have long been overlooked, but are now gaining serious traction.

blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiaiion. nsights/china-green-finance-status-and-trends-2024-2025

Wellness Economy

A second branch of the ecological economy is also low profile – in its case, because it caters for the most prosperous 1% of the world’s population. It’s called the Wellness Economy.

I did not realise until a week ago, for example, that, as I read in Vogue magazine, “regenerative farming is the latest wellness travel trend”.

Babylonstoren, in South Africa, is a startling example. This 200 hectare working farm has been described a “the Versailles of vegetable gardens”. For $500 and upwards a night you can stay among all this edible botanical beauty, live slowly for a while, and pamper your body in a super-luxury spa.

But high-end agritourism, to its credit, is not just about self-pampering spas. Babylonstoren also offer dozens of workshops and learning experiences. Their focus is on heritage crafts – from cutting and curing venison, and making vinegar, to leather work, bookbinding, and the basics of ironmongery.

babylonstoren.com/workshops

High end agricultural tourism is not much preoccupied with social justice, it’s true, but it’s a pretty large niche within a range of activities devoted to ecological restoration.

According to its trade body, Global Wellness (globalwellnessinstitute.org) is a hefty $6.3 trillion dollar economy. As well as Wellness Tourism, like that farm in South Africa, extensive ecosystems of people are engaged in wellness Real Estate, Spas, Springs, Complementary Medicines, Healthy Eating.

All of these involve work for designers.

AgriTech for Agroecology

High-end wellness agritourism, like that farm, may be niche for the riche, but agroecology – also called ecological agriculture, or natural farming – matters to us all.

The world’s small-scale farmers – including at least 250 million here in China – feed the world a with less than a quarter of all the word’s farmland.

With their a closer relationship with their land than remote ‘production agriculture’, they also steward 80% of the world’s biodiversity.

This is why, if public health & wellbeing are indeed the centre of an ecologiocal economy, then the world’s 1.6 billion small scale farmers are, for me, the most important health workers in the world. https://apcnf.in/

Can they fare better? Of course. The design opportunity, now, is to search for small practical ways to improve one aspect of the natural farming system.

Now for many design people in cities, their first thought has been about technology – and there’s a lot of excitement about AgTech as a potential market. Last year there were 5,000 agtech startups in China, more than 6,000 in India.

But there’s been almost zero participation by the world’s small scale farmers in this so-called innovation boom.

But here’s a thing. These ‘everyday experts’ are not anti-tech. Peer-to-peer, open source knowledge exchange is widespread in this movement,

Indeed, a new grassroots movement, Grassroots Innovations Assembly

(GIA gia-agroecology.org) has identified three pathways ways to enhance agroecology, using tech:

- Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) systems and frameworks;

- New market pathways for the products of small scale farmers;

- Facilitate the co-creation and exchange of knowledge on agroecology.

Social innovation has a huge role to play in natural farming. Ecological agriculture is as much a social movement as a biochemical one – and, for me, the most dramatic impact of technology on food systems is a social one: putting farmers in direct contact with the city people who eat their produce.

Another example is fashion

For 35 years the “sustainable fashion” movement has struggled to find workable solutions – and we have largely failed.

Circular systems. Regulation. Renting. Recycling: Their effect has been marginal. A focus“do less harm” has been overwhelmed by a Great Acceleration in the material and energy throughputs of the global fashion system as a whole.

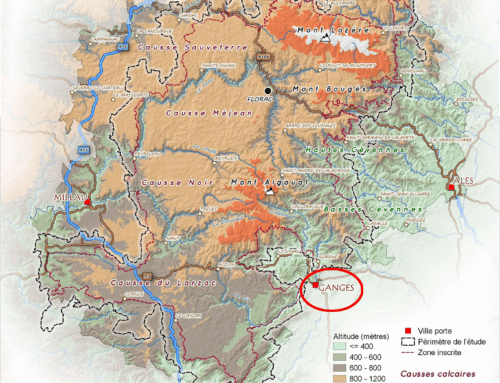

But there is one positive development we can build on: bioregional fashion systems. This is when fibre reproduction (plants and animals), design, processing and use, are integrated with land, soil and watershed care.

The Fibershed movement is by now a tried and tested example of this emerging synthesis. Check out, for example, Pennsylvania Fibershed. https://pafibershed.org/

Living infrastructure

In the USA, the Safe Clean Water Program: safecleanwaterla.org, allocates multi-million dollar budgets for infrastructures to mitigate droughts, heat, floods, and wildfires.

Until recently, it was well nigh impossible for ordinary citizens to choose what project to do, obtain permissions, or secure funding. Often, such information already exists – but in a multitude of specialised databases and municipal offices.

In Los Angeles, the Living Infrastructure Field Kit, is a free tool for L.A. residents to plan and fund local living infrastructure projects. livinginfrastructure.org

The tool can be used to map out rainwater capture for community garden, for schoolyards, parks, or green streets,

The Living infrastructure Field Kit provides a single point of access to 65 of the most detailed datasets available across L.A. County – normally known only to professionals. The Field Kit provides access to regular citizens through an intuitive interface.

Building on this work one of its designers, Steve Daniels, is now working on companion project – Terrain – that he says is a “tool for ecological intelligence”.

Terrain helps planners, land trusts, fire councils, and watershed groups target interventions to heal landscapes.

As with the Field Kit, Terrain integrates a deep library of geospatial datasets. But instead of requiring advanced GIS skills, you can simply ask questions in natural language—powered by LLMs.

Nature Connection and AI

EdenX is a digital platform, based on artificial intelligence, that enables more than human modes of dialogue about rivers, and their rights.

2024.xcoax.org/pdf/pestana.pdf

For me, Eden-X is an example of nature connection in which AI – as a medium of experience and learning – can enable relationships that reconnect man and nature.

In addition to being a platform for dialogue, EdenX works as a decentralized and self-managed deliberation and decision-making tool in which all stakeholders can make proposals and vote on proposals made by others.

This conversation you see here was displayed in a spatial setting that allowed viewers to be immersed in the fluid, watery universe of the assembly.

Here, AI re-awakens our capacity for ecological thinking – the ability to see the patterns of life as a connected whole in which we humans are a part.

This functionality is literally vital: The greatest challenge of our time is to foster widespread awareness of the hidden connections among living and nonliving, things.

Conclusion

I explained, at the outset, that because green design meant “do less harm” in an extractive economy that was growing exponentially, we ended up doing more harm.

Green design, I suggested, was best thought of as a warm-up period for ecological design based on simple propositions:

- When our places gets healthier, so do we.

- The health of people, and place, are a higher form of value than money,

or GDP. - Caring for place creates value.

I then told you about economic spaces in which new jobs and livelihoods are to be found for today’s, and tomorrow’s designers: earth repair; the wellness economy; technology support for natural farming; and nature connection.

Each of these involves ecological and social care in combination. It’s not a questions of either, or.

For business leaders here, I hope I’ve persuaded some of you that place-based partnerships for social change – Business2Place, or B2P – can be materially beneficial to your organisation. An ecological approach is not about box-ticking: it involves you in sustainability you can touch, and feel.

For all of us, the study of living systems tells a consistent story. Ecological design means engaging with nature as a complex of constantly changing lifeworlds.

Whether it’s sub-microscopic viruses, mosses, and mycorrhizae – or trees, rivers and climate systems – the health of an ecosystem lies in the vitality of interactions between its component species. Science has confirmed an ancient wisdom: All natural phenomena are not only connected – their very essence is to be in relationship with other things – including us.

So I conclude with the words of Andreas Weber . Our task now is to

design for shared aliveness

Contents: