Dr Martin Schuepbach from Dallas, Texas, has the following plan, concerning natural gas, for the Cevennes region of France, where I live [below]:

First, he will take millions of gallons of our clean mountain water. To this he will add a cocktail of up to up to 600 toxic chemicals including highly corrosive salts, carcinogens like benzene, and radioactive elements like radium.

He will then pump the noxious mixture deep into our ground.

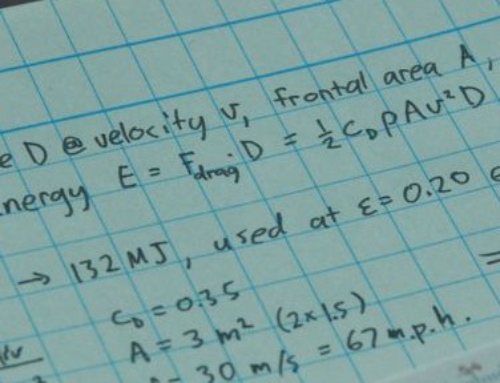

When this hydro-fracking process as it’s called, has done its work, and natural gas has been extracted, Martin’s people will dump some of this poisoned water into open pits on the site – similar, one imagines, to the one shown below:

The rest will be left underground where some of it is highly likely to poison our ground water. He hopes to repeat this Halliburton-designed process dozens of times, all over our region.

Dr Schuepbach’s plan is not illegal. Although hydro-fracking at one well uses as much water in three days as a Cevenol village with 1,000 inhabitants consumes in four years, he has a permit.

The Permit of Nant as it’s called, was granted last year to Schuepbach Energy LLC by the French government. The area granted is shown on the map below.

This decision was not, to put it mildly, widely publicized – but word has got out and we are all now cross.

We’re also pretty amazed to discover who is behind this plan. Dr Schuepbach is its front man, but a good deal of the money to pay for it comes from a venture fund, CIC Partners, whose Managing Partner is a confidant of George and Laura Bush. [Marshall Payne is the guy in the blazer on the right in the photo below. He is co-chair of the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy. Laura Bush is in the middle]

Now I like Texas a lot, so it’s distressing to me personally that Texans could be behind this ecocidal plan. I’m sure a misunderstanding occurred when Martin and Marshall were discussing the Nant project at the Dallas Country Club [I’m guessing the location].

The Cevennes must have looked, on a map, like a largely empty area containing only rocks, trees, and a few poor people in small communities who would cause little trouble. The mischevious French government, when granting the Texans their permit, may well have emphasized this tranquil image.

What the Texan contingent may not have realized is that the Cévennes has been famous for its resistance to centralized tyranny since the early seventeenth century and before.

The Camisards, for example, were effective rebels against both Crown and Catholic Church. They pretty much invented guerilla warfare whilst opposing the armies of Louis XIV, the absolutist ‘Sun King’, over many years.

In the long run they lost…

…but, ever since, there’s been a tacit agreement between the French state, and the Cevennes, to leave each other alone.

Foreign invaders have not been so wise. During the Nazi occupation of France, for example, the Cévenols [as inhabitants here are called] hid and protected large numbers of Jewish children and German deserters. Fugitives especially at risk were guided over old sheep tracks high in the mountains and hidden in wood-cutters huts or sheep stalls.

Many of these are still used. The Cévennes landscape and culture proved to be ideal for armed partisan operations against the occupiers and their collaborators.

Mistrust of all things from Paris and beyond has not diminished in recent times. Au contraire. In 1999, a famous son of the region, José Bové, leader of the farm-workers’ union, trashed a McDonald’s restaurant with a mechanical digger. He was given a three-month jail sentence, but 40,000 supporters turned out in his support at his trial.

Today, a decade on, Bové has been elected to the European Parliament as a member of Europe Écologie, a coalition of French environmentalist political parties. He is vehemently opposed to Gaz de Schiste.

So what happens next? In March, 80 French parliamentarians signed a motion against the exploitation of shale gas. Shortly afterwards, the government extended a moratorium on shale gas exploration until June when two official reports are due to be published on the environmental impacts of ‘unconventional resource development’.

Although natural gas has acquired a reputation for cleanliness, this is largely based on its lower carbon dioxide emissions when burned. It emits roughly half the amount of carbon dioxide as coal and about 30 percent less than oil.

Less publicised, and much uglier, are the emissions over its production life cycle from the moment a well is plumbed to the point at which the gas is used. The dangers posed to our water supplies by the hydrofracking process, and the effects to both health and the environment, are much more severe that was previously assumed. The toxic chemicals used in fracking can leach into the water supplies that, as the Oscar nominated film Gasland showed, it has been possible actually to light water as it comes out of the tap.

The Texans’ plans for the Cevennes are being shaped by a bigger energy politics picture. A global rush is on to tap the Earth’s deep gas-bearing shales miles beneath the surface. The fracking process is being sold as being less damaging to the environment than coal and oil – and anxious policy makers, as they wise up to the electorally-terrifying implications of peak oil, have been ready to go along with with the idea.

Now, as the carefully cultivated ‘clean’ image of shale gas melts away under scrutiny, plans in places like France may progress slowly, if at all.

There’s a danger, though, that the ghastly human and environmental damage of hydrofracking will weigh heaviest on poor countries with less capacity to resist.

Sorry, Dr Schuepbach, but this process should not happen in anyone’s back yard.