This three-way dialogue – Karin Fink, Marguerite Kahrl, and John Thackara –

took place on the occasion of

HABITAT: THE RELATIONAL SPACE OF BEING

at Simondi Gallery in Turin

(September-November 2024 HABITAT)

Marguerite Kahrl: The collective exhibition Habitat: The Relational Space of Being probes the visible and invisible networks surrounding and connecting living systems. It provides an opportunity to reflect upon advocacy and embodied experience as we consider how to repair and maintain the infrastructure on which we and other nonhuman entities depend. For example, soil health is the foundation of our habitat and health, yet this vital connection has often been overlooked. While some people maintain a distant relationship with soil and may consider it unclean, we now understand that soil microorganisms are essential for the evolution of our gut microbiome and immunological resilience 1. How do we determine our soil’s health 2, and what insights can we gain from it as we reframe our relationship with the natural world?

John Thackara: This exhibition has been a timely incentive for me to reflect on my own changing relationship with soil. I’ve spent a good chunk of my life as an author and curator trying to understand why we humans continue to trash the planet with such careless abandon. Several decades on – I’m a slow learner! – the notion of a metabolic rift between us humans and the living world now makes good sense. We’re cognitively and culturally separated from the living systems we live among. Seen in this way, I don’t think that I “maintained” a distant relationship with nature. Rather – along with a few hundred million of my fellow over-educated humans – I was preoccupied with other concerns – and these concerns existed mainly in my head: ideas, concepts, arguments, language, reputation, and money. The biggest revelation for me is that we don’t have to argue for a better relationship with nature or provide evidence that it would be a good idea. Those relationships are innate in us all. We just need to do it – reconnect. There’s soil a few centimeters under these typing hands. A few meters from this desk, I can walk on soil in my bare feet. I just need a trigger to do so. And that’s where art comes in.

Karin Fink: I believe that we have gradually distanced ourselves from the natural world, prioritizing intellect and technological advancements. Now, we long for a connection with nature and wilderness. Slowing down and incorporating our capacities could help us create a different presence in the world. Human curiosity and willingness to build and explore (which triggered the distancing development) are still necessary resources. By combining technological, infrastructural, and organizational abilities with a slower pace of life, both as individuals and communities, we could make room for a different way of living. The current societal and ecological crisis presents us with many uncertainties, and we can learn something from the field of soil science.

The Swiss government writes: “In Switzerland, the majority of soils recorded to date are agricultural soils. Today, however, sufficient qualitative soil information is only available for around 13% of agricultural land, which means there is no solid ground for making decisions on the sustainable use of soils. In 2020, in addition to adopting the Swiss Soil Strategy, the Federal Council therefore also issued a mandate for nationwide soil mapping.” 3

Why do I quote this? I find it interesting that even in 2024, soils are a big unknown to us humans. Even more, it makes me quite hopeful that the government is willing to explore and expand its range of knowledge. The program is quite costly, and the Swiss Confederation is willing to pay for it. Bruno Latour sketched this out in Down to Earth:

“What to do? First of all, generate alternative descriptions. How could we act politically without having inventoried, surveyed, measured, centimeter by centimeter, being by being, person by person, the stuff that makes up the Earth for us?” (…) We must agree to define a dwelling place as that on which a terrestrial depends for its survival while asking what other terrestrials also depend on it. (…) It is a matter of broadening the definitions of class by pursuing an exhaustive search for everything that makes subsistence possible. As a terrestrial, what do you care most about? With whom can you live? Who depends on you for subsistence? Against whom are you going to have to fight? How can the importance of all these agents be ranked?”. 4

These questions help us gain a better understanding of soil and learn how to navigate when the knowledge produced by industrialized society is being reconsidered. We are beginning to recognize its limitations. As Latour writes, “We need alternative descriptions.” What might these alternatives look like?

All that mapping – of soils or relations – might make us see, but what will make us do? What will make us heal the metabolic rift? And in what ways? We are trained mappers but need to be trained healers. And here, art can build a bridge… What might contemporary mapping of the unknown look like? How can we draw from human curiosity, the love for building and creating and making, and the desire to achieve more? How might art help us process it?

JT That Swiss government statistic is startling: “qualitative soil information is only available for about 13% of agricultural land”. That number raises questions: what does ‘qualitative’ mean? And why does it matter that so much land remains so thinly understood?

I would like to think, Karin, that your government recognizes that soil care and repair are not just technical matters but also social and cultural ones. If that is correct, then I commend a new word to your colleagues that I recently discovered— “ethnopedology” 5 . It’s a research practice that compares local people’s knowledge about their soils to scientists’ knowledge.

There’s enormous interest and investment at the moment in planetary observation at different scales – from satellite observation to microbiome analysis. It’s now becoming possible to monitor every forest, every tree, and every city block on Earth on a daily basis. Its advocates say such real-time ecological dashboards can be a game-changer in planetary care. I’m not so sure. For me, it is a contested question whether (or not) exposure to more (and new kinds of) data causes citizens to behave differently – for example, to care more for their local soils and ecosystems.

MK The process of mapping data supports policy-making and enables us to gain insights that can help us protect our ecosystems. However, to change our behavior, we need to do more than simply rely on short-term measurements and analytical tools. The need a variety of responses to transform our culture and explore new forms of shared action and coexistence. Many artists and designers have taken up this challenge with local projects emphasizing care, repair, maintenance, and adaptation of the commons. We must move past observing the climate crisis to feeling it in our bodies and processing this with actions. Collective actions can help us untangle colonial paradigms and shift emphasis from ‘rational knowing’ and power-over dynamics to ‘embodied knowing,’ intuitive skills, connection, and touch.

This new paradigm of action is showcased in “The Great Repair,” 6 , a publication and traveling project examining the contradictions between growth and ecology. It addresses how architecture can be a reparative force for the socioecological crisis and investigates whether repairing politics and aesthetics from a decolonial, feminist, and posthuman perspective can offer a meaningful alternative. Kader Attia, one of the contributing artists/curators, touches on repair as a form of agency.

“Thinking about repair has become a tool for revealing the ways in which we are all still living in the colonial laboratory. But I think it is important for research into this topic to always begin with a physical object or tangible context – an object, a building – and then slowly branch out into theoretical reflection. Not vice versa. What often happens today is that we theorise a lot and then grasp for examples that incarnate what we are arguing. It is like the idea of care. We talk about care, and then we organise dinners. We should organise the dinner first and get in touch with the materiality of that tangible experience. And then, slowly, through a collective individuation process, we share ideas and feelings and dare to imagine.” 7

I see ethnopedology as one of Latours’ “alternative descriptions.” It combines local and scientific knowledge about soil while acknowledging different cultural conventions, perceptions, uses, and management styles.

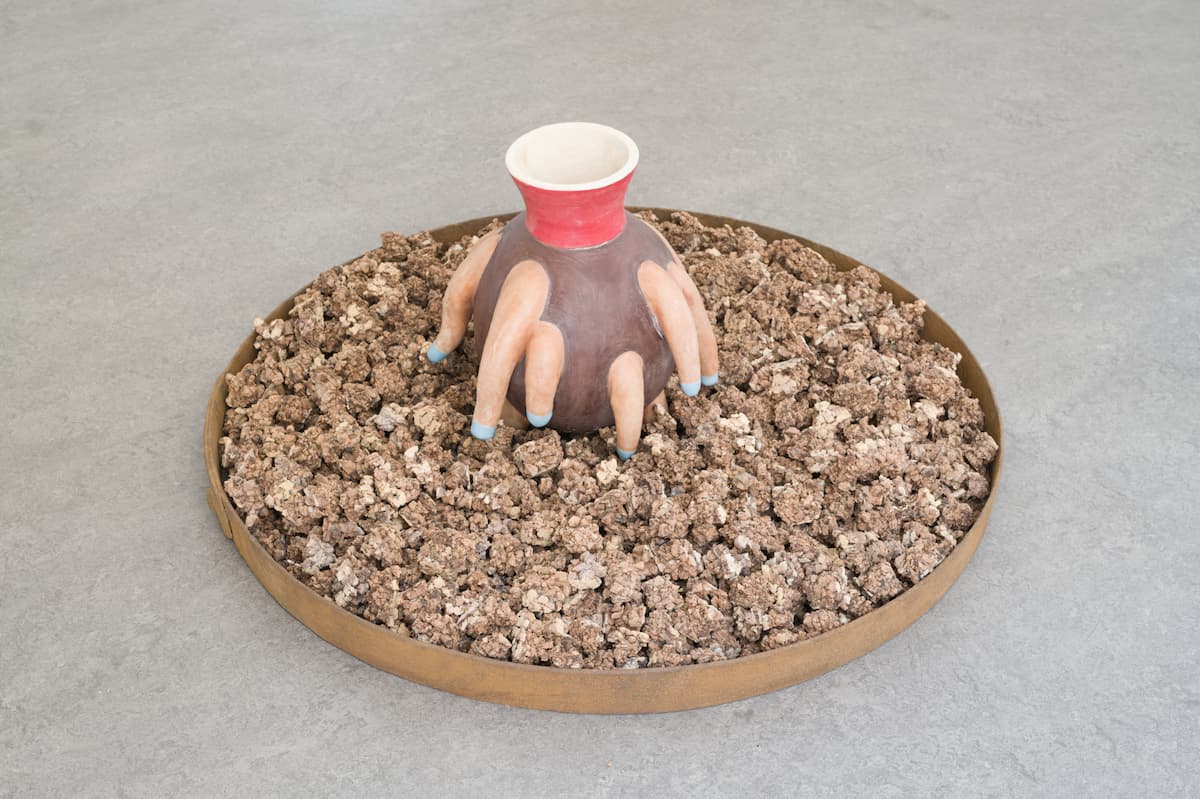

For Irrigators: Underground Conversations, I built and buried irrigation vessels in neighbors’ gardens to investigate and share irrigation and cultivation practices. Within a 10-km radius, I noticed significant differences in soil types, management, and absorption. The objects served as a tool to access local knowledge, build soil fertility, create a network of users, and showcase their diverse gardening techniques.

KF We have enough knowledge about our soils and the ecosystems at risk. Nevertheless, I still see the old ways of observing, mapping, and charting as a way to learn about the otherness of an entity (a body, a system?) like soil. I watch scientists take their samples – to do so, first, they have to access the land and converse with the landowners and farmers. This “nationwide” exercise is as much about gathering data as it is about conversations between different worlds. As you, Marguerite, did in Underground Conversations, I hope that the scientists not only measure humidity and pH but also collect information about the long-term observations from the people they meet on the land. Setting out to chart the unknown territory of soils is as much about the storytelling as the facts. Over time, a picture of the land will emerge, revealing areas where the soil needs restoration or protection from erosion and where the chemical properties are out of balance and need rest. Repairing soils is extremely time-consuming, sometimes requiring decades to replenish. To overcome such long periods, we need good stories to tell – stories that pass on knowledge about what is going on in a specific patch. Objects like the irrigation pots may act as a reminder.

JT It’s not about more data or less – it is about the social contexts in which data is collected, discussed, and acted upon. The same lesson applies, I think, to discussions about ‘nationwide’ and ‘local’. We need to operate at both scales. I recently met someone involved in efforts to clean up Chesapeake Bay in the US – a forty-year-long effort. More than 200 organizations are involved in just one platform, Choose Clean Water. After years of people blaming each other for causing the problem, a focus on hyper-local stream repair seems to be providing common ground. Finally, instead of talking about nutrient reductions in a Bay many miles away, they can talk about improvements in streams where their kids and grandkids play. According to Karl Blankenship, in the piece I just read, the following actions are local, too: targeted areas are typically stream segments that are only a couple of miles long and drain watersheds of 1,000–5,000 acres with 10–15 landowners. 8 Acts of care are local and embodied – but when many of those actions are added together, the results can be system-wide.

MK Social context matters. Community engagement is crucial for local development, but what happens when it is driven by fear of pollution, outsiders, climate change, or maintaining privilege? What if we genuinely had to adapt to our chosen habitat? How can such hyper-local repair acts influence the “Not in My Backyard” movement- which opposes or resists change in communities? Dr. John Todd, the founder of the New Alchemy Institute (NAI) 9 , believes that by combining the knowledge accumulated in the last 100 years, we can achieve things we never thought possible. He emphasizes that “we don’t have to invent anything; we just have to pay attention to what’s been learned.” 10 NAI interpreted ecosystems, such as the ‘living machine,’ to filter water by imitating the functions of marshes, ponds, and streams. This type of design can help us sense whole systems and their qualities, patterns, and potential.

So, how can we pay attention and become enchanted to act? This is where artists come into play. With their ability to question, confront, engage, and captivate, we may better understand and interpret our habitat and its environmental and social contexts.

NOTES

1 Marja I. Roslund, “Scoping review on soil microbiome and gut health—Are soil microorganisms missing from the planetary health plate?”, British Ecological Society, (2024): (online).

In besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pan3.10638 (last accessed 01/08/2024)

2 We have discovered that soil and human gut bacteria share functional similarities. Soil-tasting ceremonies or the Museum of Edible Earth could be interesting parameters to monitor and accentuate this relationship.

3 Karin Fink translation from bafu.admin.ch/bafu/de/home/themen/boden/fachinformationen/bodenkartierung.html (last accessed 18/07/2024).

4 Latour, B. (2018), Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Paris: Polity Press.

5 N. Barrera-Bassols, J.A. Zinck. “Ethnopedology: a worldwide view on the soil knowledge of local people,” ScienceDirect (2002): (online). In sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S001670610200263X (last accessed 25/07/2024).

6 The Great Repair – Politics for the Repair Society (online).

In archplus.net/en/archiv/english-publication/The-Great-Repair/#article-7081 (last accessed 15/07/24).

7 Kristina Rapacki, “Interview with Kader Attia”. The Architectural Review, (2024): (online).

In architectural-review.com/essays/profiles-and-interviews/interview-with-kader-attia.(last accessed 15/07/24).

8 Karl Blankenship, “Will A Focus On Stream Health Help Boost The Chesapeake?” Bay Journal (2024): (online).

In thebaynet.com/will-a-focus-on-stream-health-help-boost-the-chesapeake/ (last accessed 22/07/2024).

9 newalchemists.net/publications/new-alchemy-1971-1991/(last accessed 22/07/2024).

10 Steve Rose, “The New Alchemists: Could the Past Hold the Key to Sustainable Living?” The Guardian (2019): (online).

In theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/ng-interactive/2019/sep/29/the-new-alchemists-could-the-past-hold-the-key-to-sustainable-living (last accessed 22/07/24).