When I arrived at Angsbacka, the site in Sweden of last weekend’s first Future Perfect festival, an alarming array of leaflets was on offer in the foyer : ‘Shamanic De-Armouring’; ‘How To UpGreat Your Life’ or ‘Reach The Temple of your Inner Beauty’; ‘The Journey to Bliss’; ‘A Cellular Dance of Oneness’.

My first reaction was: Beam me the hell back up, Scotty.

My second reaction was: to give the place a chance. There are many reasons to be sceptical about the alternative culture movement. It can reinforce the myth that we can consume our way out of environmental collapse. It implies that personal lifestyle choices can be an antidote to an industrial growth economy that destroys the basis of life on earth – including our own. For Lierre Keith, a founder of Deep Green Resistance, Angsbacka-style alternative culture encourages ‘a continuum that runs from the narcissistic to the sociopathic’ – and she poses a stark question: “Do we want to manage our emotional state, or save the planet? Are we sentimentalists, or are we warriors?’.

FuturePerfect was not a training camp for a new eco-warrior caste; too much hugging for that. But neither was it an infantile self-love fest. The atmosphere was adult, and more intentional than introspective. What emerged was an intriguing synthesis of mindfulness, and designfulness.

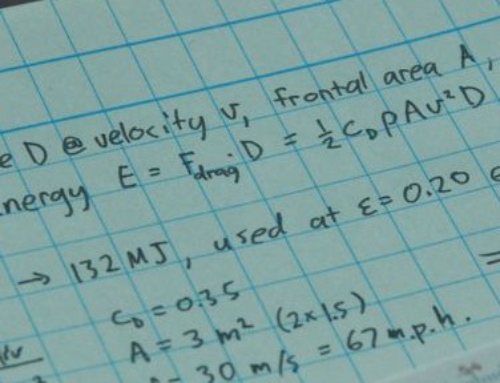

Mindfulness, for the FP crowd, meant facing up honestly to how serious the challenges have become. Peak energy, climate weirdness and global food insecurity, someone said, are potential ingredients of a ‘global Somalia’. Hardly a happy-clappy sentiment. There was acceptance, too, that these challenges will not magically be ‘solved’ by technology – nor designed away – within the economy we have now.

Designfulness, at Future Perfect, meant a sober commitment to take practical actions that can be the seeds of the alternative economy we have to grow. Several discussions about money exemplified this commitment to reflective action. For most people ‘the economy’ is an abstract concept that is hard to grasp, and seems impossible to influence. A local money system, on the other hand, is a tool, and a service, that enables co-operation among people and groups. Local money is also a service design challenge that many people at FP could relate to.

The process by which we design a new economy is as important as its components. Future Perfect’s creator, John Manoochehri, banned powerpoint presentations, for example. This sounds like a detail, but it meant that our conversations were face-to-face, not face-to-screen. Direct, embodied communication between people – rather than the abstract, mediated kind that dominates the sustainability discourse – helps dispel the illusion that we humans are separate from the rest of the natural world.

That re-connection with the biosphere came literally to life in the stunning permaculture garden at the centre of the Angsbacka site. A six person cooperative called Flow Food provides a lot of the amazingly good food eaten at Angsbacka’s festivals. For the Flow Food group, no chemicals, no machines, no transport are practical and highly effective collaborative arrangements, not a utopian ideology.

Can a permaculture garden in rural Sweden, and a ban on powerpoint, be more than a pleasing distraction? For Lierre Keith, at Deep Green Resistance, the ‘open-hearted state of wonder’ cultivated at sites such as Angsbacka is a pathetic response when a planet is being murdered. ‘Are we so ethically dumb that we need to be told that this is wrong?’, she asks.

It’s a harsh but necessary question. For me righteous rage, and direct action, will be no more effective than green consumerism in effecting the changes we need to see. Perhaps my mind was turned to mush by the Angsbacka vibe, but the lesson I draw from Future Perfect is that, yes, the ecocidal industrial economy needs to be stopped – but we are more likely to achieve that by replacing it, than by kicking it. And as a growing medium, Angsbacka was the right place for FuturePerfect to be.