Yesterday’s G8 Dementia Summit made much of the fact that millions will now be spent in a race to identify a cure or a ‘disease-modifying therapy’ for dementia. The likely outcome will be the creation of a Dementia Industrial Complex – and the mass production of un-met expectations.A better way for nation states to spend money on dementia is in the ratio: 95 per cent for Care, five percent for Big Research.

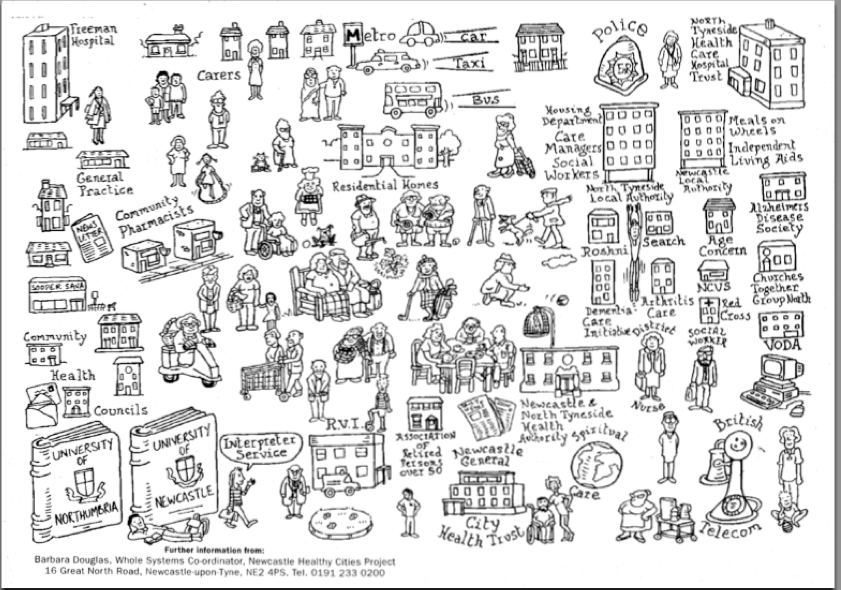

(Above: the demential care ecology of Newcastle, in North East England. Illustration by Barbara Douglas)

When War was declared on Terror, a Security Industrial Complex (SIC) boomed. For the purveyors of full-body scanners, high-end police trucks, and Total Information Domination software, Terror has been good business. But is the world is a safer place? The SIC and this writer are aligned on the question: No, it is not.

The proclamation of a war on dementia – at yesterday’s G8 Dementia Summit in London – promises similar divergence between language and effect. The G8’s communique made much of the fact that millions will now be spent in a race to identify a cure or a ‘disease-modifying therapy’ for dementia. Although this announcement was not unexpected, the false promise of an imminent cure for dementia will surely divert resources to Big Research at the expense of support for care ecologies that already exist.

During yesterday’s summit, I was visiting with two elderly people in England. One of them suffers from acute short-term memory loss; the other has severe mobility impairment. During the day: a carer came to help one of them get up; a second carer came to check on his progress at mid-day; a physiotherapist came to do getting-up-the-stairs training; a district nurse (accompanied by a student) came to do a blood test; a pharmacist came to deliver a multi-compartment box pre-loaded with a week’s worth of pills; a team leader from the care company came to check how things were going; a man from Mobility Supplies delivered a Perching Stool for the bathroom; a gardener came to rake the leaves; a man came to fix the computer; a neighbour came from upstairs to say hello; and another carer came to help put the mobility-impaired man to bed.

Apart from the gardner, the computer guy, and the neighbour, all these caring professionals were being paid for – directly or indirectly – by the British state. Therefore, as I followed #G8Dementia on the interweb, I felt sympathy for the politicians and global dementiacrats assembled in London. Care at the level I witnessed in England – to which hundreds of millions of voting G8 citizens feel they are entitled – is not financially supportable. It’s not untrue: Something Must be Done.

That Something is not a war – but the airwaves resounded yesterday with words like ‘fightback’, ‘crisis’, ‘killer’, ‘timebomb’, ‘victims’, and ‘battle’. As many dementia sufferers and their carers have attested, the language of war in medicine makes things worse for them on the ground. It worsens the the stigma attached to the condition and increases fear in the broader population. The net effect of war-speak is to diminish social solidarity. Such language also demeans millions of sufferers and carers: Depicting people as helpless victims – as refugees from a lost battle – disrespects and undervalues the often admirable lives led by an infinitely diverse group of people.

Other reporters used words such as ‘cruel disease’, ‘robs you of your mind’, or ‘horrific’. No report, that I saw, explained calmly that the word dementia covers more than 100 associated but different end-of-life conditions in which brain cells die on a huge scale for reasons….well, nobody really knows. Some of yesterday’s media coverage was plain misleadin:. One BBC reporter delivered his piece whilst standing beside a million euro brain scanner – like a salesman for Siemens. Cutaway shots featured computer visualizations of peoples’ brains – a visual language that reinforced the myth that dementia can be compared to a tumour that, given fancy enough technology, can be cut out.

Hints of an an imminent cure for Alzheimer’s are misleading and irresponsible when made by journalists, or Big Pharma lobbyists. For the UK’s Health Minister to that “a cure for dementia could be just seven years away due to ‘incredible advances’ in medicine is downright cruel. The truth was given by Dr Margaret Chan, Director General of the World Health Organization: ‘In terms of a cure for dementia, or even treatments that can modify the disorder or slow its progression, we are empty-handed”. So-called memory-boosting drugs, for example, have been found to have very modest effects. There is no evidence in humans that they slow the rate of progression.

Mass screening for dementia is another distraction. One consequence of that expensive gesture will be a cohort of distressed people who will be told they have dementia, when they do not. Dementia tests are not especially accurate, and yet a misdiagnosis will be devastating when the misdiagnosed know full well that we can’t do much about the condition.

Care before cure

In contrast to the grand promises made in London, the appropriate way for nation states to spend money on dementia is in the ratio: 95 per cent for Care, five percent for Big Research.

I do not pluck those numbers out of thin air. They correspond to the structure of the functioning care economy we have now. In Wales, for example, which is not untypical of industrialized nations, unpaid carers provide at least 96 percent of annual care hours; the remaining four per cent are provided by local authorities and independent providers. Those 340,745 unpaid carers are equivalent to 11 per cent of the country’s population. In 2001, they provided at least 288.5 million hours of care; local authorities provided 11.7 million annual hours.

As I experienced this week in England, caring for cognitively impaired people, and for older people generally, is time and resource-intensive. No society can afford to pay indefinitely for the ‘delivery’ of costly services to an ageing population. But perhaps ‘delivery’ and ‘pay for’ are the wrong words. The one sure way to improve life for people living with dementia is to ask them: What practical steps might improve your lives? With that to-do list as our guide, the social innovation task becomes: by what means can we, collectively and affordably as a society – co-create those measures?

The main points of this to-do list are already known. During Alzheimer 100: the Journey through Dementia, for example, six issues were identified as being of particular importance to people with dementia and their carers:

First experiences (including listening to families; the training nurses and family doctors);

Early stages (including exercise, nutrition, mental stimulation; what to do at known trigger points – such as falls, or bereavement);

Stigmatization (the need to find spokespersons and advocates; elements of an awareness-raising campaign; training for the media);

Enabling and assisitive technology (the need to put people with Azheimer’s at the centre of the development process; assistive technology combined with people-based services; of the sample we talked with, tech was a priority for 18 percent);

End-of-life (including issues to do with care homes; palliative care; family support; end-of-life directives; support for carers before and after death).

Around the world, many hundreds of projectsmeet some of the needs articulated above. Most of these actions are small, local, and below-the-radar. In several Nordic countries, for example, a scheme known as ‘Green Care’ enables people with dementia who live in their homes to spend time on farms where they interact with animals, plants – and children. (Green Care farms are used by kindergartens and other school projects as well as by people with dementia).

Some of the best denentia care is ‘co-created’, in the lumpen language of service innovation. Fifty percent of older care provision in Quebec is co-operative. Canada’s social co-ops have not only improved both the quality of home care for clients, but also the working conditions, wages, and professional competence of home care-givers. Coop care workers gain life-skills training. People with intellectual disabilities find employment. In Bologna, 87 percent of elder care is cooperative. In Italy, 6,000 social co-operatives provide social services. These social co-ops employ 160,000 individuals, of whom 15,000 are disadvantaged workers.

A care economy is best imagined as the support and stewardship of a care ecosystem that already exists. The beauty of this health-as-ecosystem idea is that it enables us to build on the trust between people, built up by co-presence over time, that is judged by dementia patients and their carers – at least in Britain – to be twice as important as the delivery of services by third party vendors.

Ninety five percent of dementia of care happens outside the biomedical system – among, for example, the three million British people who were caring for people with dementia before yesterday’s summit convened. If the world’s governments want to throw money at dementia, great – but they should do so on the basis: 95 percent for socially co-created care – and five percent for Big Research.