Why is it that shocking stories and images fail to change things? Are there different ways of knowing the world, than merely looking? (Revised July 2015)

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain Of Others

Do visualizations, however powerful and evocative, actually change anything? And if not, why not? Susan Sontag writes: “Compassion is an unstable emotion…it needs to be translated into action, or it withers. […] People don’t become inured to what they are shown — if that’s the right way to describe what happens — because of the quantity of images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling.”

Rick Poynor, “Should We Look At Corrosive Images?”

Rick quotes John Berger: “The picture exists to prick our consciences and provoke action, but if no action related to its origin in a specific political situation occurs, then the picture is depoliticized. It becomes ‘evidence of the general human condition,’ says Berger, accusing everybody — including the demoralized viewer — and nobody.”

Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text

“The traumatic photograph (fires, shipwrecks, catastrophes, violent deaths, all captured from ‘life as lived’) is the photograph about which there is nothing to say; the shock photograph is by structure insignificant: no value, no knowledge, at the limit no verbal categorization can have a hold on the process instituting signification…Why? Doubtless becausein relation to society overall its function is to integrate man, to reassure him”.

Strategies for Representing the Pain of Others: The Video Advocacy Institute, by Liz Miller, Martin Allor

How can human rights activists best reach audiences in a multichannel universe that is increasingly inundated with images of war, tragedy and suffering? How to avoid having your campaign lost in the sea of nonstop reality media? The Witness model of advocacy promotes ‘narrowcasting,’ the idea that it is not always how many people see a video but who sees it and what they do with it.

The Participatory Character of Landscape, by Harry Heft

In 1908, the American philosopher John Dewey described mainstream perceptual theorists of his day as being in the grip of a “Kodak fixation.” Dewey was expressing deep reservations about the adoption of a photographic attitude toward the nature of seeing, and more generally, knowing. He was critical of approaches to perceiving that operate as if the individual confronts the world as a spectator, in effect, standing passively and detached from what is experienced – much in the way that photographers stand apart from their subject.

Animate Earth, by Stephan Harding

In his book Animate Earth, an interpretation of Gaia and some of its connections and systems, Stephan Harding explains the planet is a vast living interconnected system, not the dead, mechanical object that many 19th and 20th Century philosophers and scientists in the West have based their ideas upon. “The crisis is at root one of perception; we no longer see the cosmos as alive, nor do we any longer recognise that we are inseperable from the whole of nature, and from our earth as a living being. But there is hope, for as the crisis deepens, the call of anima mundi intensifies.”

Life Rules, Ellen La Conte

The largest context – the largest high-functioning complex system within which we live our lives – is not the nation, nation-state system, or global economic system, but Life itself, the whole-earth, emergent and self-maintaining system of natural communities and ecosystems.

The Surre(gion)alist manifesto, by Max Cafard

For Cafard, Utopianism is the search for a higher, deeper or better reality in some other place. Topianism means simply (and at the same time very complexly) being here. The surre(gion)alist concept is that we be open to finding the unexpected in the evident, the unique in the common, and the extraordinary in the ordinary.

The Practice of the Wild, by Gary Snyder

Gary Snyder shows us that we can also prowl the urban woods and streams, the great wilderness at the heart of the city, if we know how to look for the things themselves there also.

Staying With The Trouble, Donna Haraway

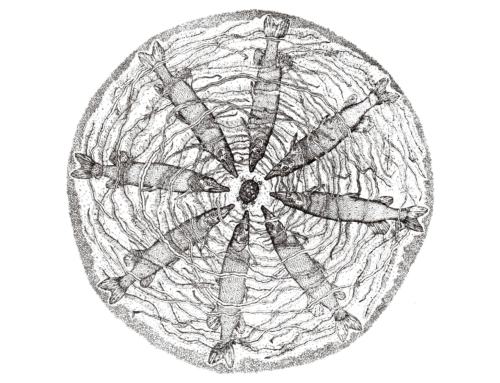

According to the theory of symbiogenesis, viruses, bacteria and many other slimy and wretched ‘things’ take part in setting our course. This leads to a more inclusive view in which all of life’s agents participate. It teaches us to give back, and not just to take. We become better, more conscious actors in the world, just knowing that we are beings intricately interwoven with our environment.

Where does the mind end and the world begin? by Teed Rockwell

Until recently, philosophers tended to think of the nervous system as a glorified a set of message cables that connect the body to the brain. But philosopher Teed Rockwell thinks that the boundary between mind and world is a flexible one. Rockwell draws on developments in neuroscience to demonstrate that the mind is hormonal, as well as neural. It follows from this discovery that the borders of mental embodiment cannot neatly be drawn at the skull, nor even at the skin. For Rockwell, mental phenomena emerge not merely from brain activity but from a single unified system embracing the nervous system, body, and its environment.

Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature

Romantic notions of nature form the greatest obstacle to developing ecological awareness and eco-literacy. When you realize that everything is interconnected, you can’t hold on to a concept of a single, solid, present-at-hand thing “over there” called Nature. ecological thinking is a position that assumes mutual connections between humans and their surroundings.

Soil and Soul, by Alastair McIntosh

It is easy to feel helpless in the face of the torrent of information about environmental catastrophes the world over. In Soil and Soul, Scottish writer Alastair McIntosh shows how it is still possible for individuals and communities to take on the might of corporate power and emerge victorious.

Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on Survival and Resistance, by John Berger, ‘

“The longer one looks at Jitka Hanzlová’s pictures of a forest,” he writes, “the clearer it becomes that a breakout from the prison of modern time is possible.” His work insists on the need to stay with lived experience, and particularly the experience of those outside the walls of the centres of power. (Also recommended by Dougald Hine)

The Other Side of Eden: Hunters, Farmers and the Shaping of the World, by Hugh Brody, ‘

Brody has spent over forty years as an anthropologist and an advocate working on behalf of tribal peoples. The central theme of his work is that these people are not “living in the past”. They are our contemporaries. He describes people making deliberate choices about which technologies they do and don’t wish to adopt: what is and isn’t compatible with the way they want to live.

Amador Fernández-Savater

“Don’t fight the powerful directly for power, be the message-bearer of a new concept of the world”. This kind of politics is about a cultural or even aesthetic transformation, an adjustment in perception that changes the threshold of what is seen and what is unseen. It’s a change in sensibility about what we consider compatible or intolerable in our existence. Above all it’s a transformation in the idea of what’s possible.

Manifesto for Homeland Earth, by Edgar Morin

All the great transformations have been unthinkable until they actually came to pass. Even up to 1950-1960, we were living on a misapprehended Earth, on an abstract Earth. We were living on the Earth as object. By the end of this century, we discovered Earth as system, as Gaia, as biosphere, a cosmic speck—Homeland Earth. Each one of us has a pedigree, a terrestrial identity card. We are from, in, and on the Earth. We belong to the Earth which belongs to us.

The Dynamic Way Of Seeing, by Henri Bortoft

The greatest difficulty in understanding comes from our long-established habit of seeing things in isolation from each other. What is really needed here is the cultivation of a new habit – to see things comprehensively instead of selectively. The forms of life are not ‘finished work’ but always forms, becoming.

The Metabolic Rift, by Jason Moore

Today’s global ecological crisis has its roots in the transition to capitalism during the long sixteenth century. The emergence of capitalism marked -a fundamental reorganization of world ecology’characterized by a metabolic rift a progressively deepening rupture in the nutrient cycling between the country and the city.

Inner Politics, by Sophy Banks

Among many activists working flat-out out in the outside world there’s a tendency to over-do things, and burn out. For Sophie Banks (Transiton Towns) “burnout is not a side issue”. On the contrary: our inner states are just as important to a healthy political movement as are its external activities. She describes as ‘inner transition’ the creation of a culture that enables us to be in a state of “feeling resourced, feeling empowered, feeling seen and appreciated”. We need consciously to grow a culture that creates partnership, learns to live within its resources, and is oriented towards joyful, pleasurable existence.