In which I talk to Winy Maas about the design of webs, networks and archipelagos of cities and regions. This story was published in July 2003 In Domus magazine.

Sustainable cities, working cities, are necessarily complex, heavily linked, and diverse. As the English writer Will Hutton has commented, just as local knowledge and information was key 150 years ago, when there were 80 different steps in the button-making industry, so, too, complex local knowledge and linkages are also key today if you are a software, media, care, or educational enterprise.The ideal city needs to contain a rich mixture of craft-based workshops, consultants, law firms, accountants, distribution and logistics companies, advertising agencies, universities, research labs, database publishers, and local or regional government offices. Unique skills, clusters of specialised suppliers, local roots, and a variety of human skills that are unique to a region – all these are a powerful advantage for local cities and regions on today’s economic stage.

This picture confronts smaller cities with a dilemma: they cannot realistically offer the same density and complexity of knowledge skills that a large metropolis can. The metropolitan centers have their own problems, it is true, but they will always win on diversity, which is a key to evolutionary success. So how are the smaller ones to compete?

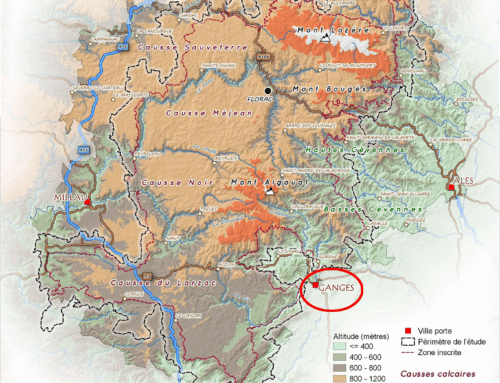

According to Winy Maas, a principal of the Dutch bureau MVRDV, the answer lies in webs, chains, networks, and ‘archipelagos’ of cities and smaller regions. By aggregating their hard and soft assets, collective cities – or multi-centered cities – can match the array of functions and resources of bigger centres, while also delivering superior social quality. The ability of small cities to offer a context that supports intimacy and encounter – what the French call ‘la vie associative’ – is where small-city webs will win out over the big centres.

City alliances are not a completely new idea. City networks date back to the thirteenth century when, in the Hansa League, an alliance of more than seventy merchant cities collaborated effectively for their common good in order to control exports and imports over a wide swathe of Europe. A powerful network of trading partners, with its own accounting system and shared vocabulary – the Hansa League became one of the major economic forces of the Middle Ages. At one stage it controlled much of Scandinavia, the Baltic states, northern Germany and Poland – and outposts can be found even today as far apart as Scotland and the Basque country.

TERRITORIAL CAPITAL

Today’s urban and regional networks can be traced back to the formation of the International Union of Cities in 1913. The Treaty of Rome, in 1957, accelerated the emergence of networks of cities and regions as supra-nation state actors in Europe. Increased globalization has put considerable pressure on cities to network among themselves – sharing, partnering and learning. Globalisation has also driven smaller cities to re-discover Hansa-style alliances, and to market them using new business techniques. According to Philip Kotler, a marketing professor in the United States, some ten per cent of business-to-business advertising – a vast amount – is now spent on marketing places, regions and nations. Kotler has identified 80,000 communities within the EU which, in one way or another, need to differentiate themselves from each other. Place marketing – or, more properly, place and regional design – aggregates and networks complementary functions and core competiencies of a region. In Europe the concept of ‘territorial capital’ is used increasingly to describe the synthesis of these hard and soft assets of a region.The hard assets include natural beauty and features; shopping facilities; cultural attractions; buildings, museums, monuments, and so on. Soft assets are all about people and culture: skills, traditions, festivals, events and occasions, situations, settings, social ties, civic loyalty, memories, and capacity to learn.

For networked, multi-centered cities to succeed, these different kinds of territorial and social and intellectual capital need to be linked together by a combination of physical and informational networks. The hubs, links, and physical and informational flows of a region need to be proactively designed in ways that help a working culture flourish.

The biggest pressure of all on cities to collaborate is environmental. Bigger cities guzzle more energy and resources per head than do smaller ones. Smaller cities, which are located closer to resources, and in which people and goods need to move less, are lighter. Cities also guzzle land. A German Federal Statistical Office forecast in 1997 that Germany would turn into a 100 per cent settled landmass within 82 years if three per cent economic growth persisted.

MULTIMODAL MOBILITY

Mobile communications are already transforming time-space relations in favour of smaller towns, working together. Where this author lives, in the Netherlands, planners hope that transport telematics will make it possible for me to to think more, and drive less. They expect to reduce so-called vehicle hours (the time spent by vehicles in traffic) by an ambitious 25 per cent. A key concept in Dutch policy is the multimodal or ‘chain approach’. The idea is that information systems will help me work out the best combination of walking, bicycle, private car, train, bus, plane, or boat – before I set off. Right now, individual transport information systems are pretty good – train and bus websites are reliable and reasonably easy to use. But they don’t work together. The next step is so to connect systems that I will enter the beginning and end points of a journey (in place, and in time) into the programme, and be offered a menu of ways to complete it.

As Nokia future-gazer Marko Ahtisaari explained at Doors of Perception 7: Flow, mobile phones can enhance proximity and reduce the allure of ‘far’. “Although mobility and mobile telephony seem very much to do with being apart, in fact the evidence is quite to the contrary,†he said. “A lot of telecommunications behaviour is aimed at getting together physically – I mean, quite simply, physically close, the stuff that happens between the one-to-ten centimetres range and room-size interaction. While we talk about devices being connected, and everything being connected in a technological sense, social interaction will be a prime driver in the future as well, even in technologically enhanced social interaction.â€

CLUSTERS OF COMPLEXITY

Architects and spatial planners started thinking about clusters in the 1960s. In 1963, Christopher Alexander and Serge Chermayeff wrote that, in designing on a large scale, “We must look at the links, the interactions, and the patterns.” Following that initial insight architecture and planning evolved rather slowly – but in recent years the sustainability agenda has given the networked approach new impetus.

According to Winy Maas, “The magnitude of information concerning a region is overwhelming: complex, and constantly changing. This multi-scalar approach is new for design. It is nearly impossible to represent all the relationships, and the webs of interdependencies, of a region. The integration of hard and soft factors is complex enough – but planners, policy makers and designers now also have to deal with a new dimension of complexity: a variety of new actors. Privatised network industries, such as railway companies, airports, electricity supliers, and telecommunications operators, are influential actors. So, too, are citizens who, with growing confidence, are demanding that social agendas – such as social inclusion, or sustainability – are factored into planning processes.

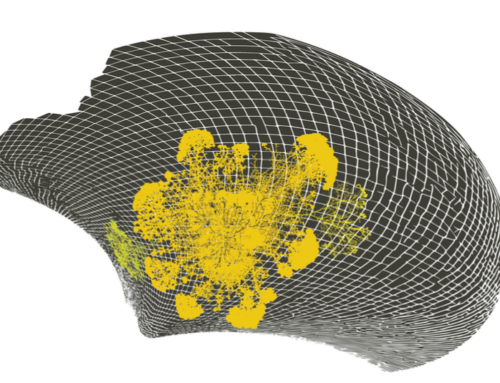

“As the speed of spatial, economical and political developments and processes accelerates, we need a more dynamic approach and tools for planning”, says Maas. ” Such tools turn massive volumes of raw data into visualizations. This is not about broad-brush visions of the idealised futures, says Maas. “We keep getting asked to make ‘visions’ for cities and regions”, Maas explains, “but I want to make planning, design and thinking tools that people can really use. We are measuring an increasing variety of things, and collecting vast quantities of data. The question is: how to use it. How are we to perceive and connect all this information in ways that add value and meaning to the raw data? Increasingly, that means how do we represent the data, visually, in order to work on and with it. We also need to make these tools more accessible and usable by non-specialised actors and stakeholders”.

THE REGIONMAKER

Maas and his colleagues have therefore become toolmakers. They have developed a family of software tools, called the Regionmaker, which was first devised by MVRDV for a project called RhineRuhrCity .The Kommunalverband Ruhrgebiet (KVR), a union of cities in the region, has invested in a series of initiatives to improve its post-indstrial situation, and today fewer than six percent work works in coal and steel. But perceptions remain that this is the Detroit of Europe, a landscape dotted with ghost towns, overgrown industries and polluted areas. “The region is very well connected logistically,” says Maas. “It has incredible water resources, a dense university system, and successful media and computer industries. But these assets are fragmented. As you find in so many places in Europe, it’s a mosaic of competing municipalities, rather than one entity.” Hence the project to reposition the area as one place, one city: RhineRuhrCity.

The Regionmaker, which combines the function of search engine, browser, and graphical interface, brings together a variety of existing information sources and flows – for example, demographic data, or outputs from Geographical Informations Systems (GIS) or ‘geomatics’, as they are now called. “In a nutshell,” says Maas, “the idea is that within the context of a globalizing world, international databanks, advanced computers, internet and intranet systems, game technology, global monitoring and information systems, can be integrated in ways that convincingly represent regions. With the Regionmaker, there is no limit to visualization. You can look at maps, study charts, access databases, export images, import video feeds from helicopters or satellites, connect to the internet, use CAD drawings, and so on.”

Maas anticipates that the Regionmaker will evolve as a tree-structure of sub-machines and routines. MVRDV have plans to add representations of knowledge on the movement of people, goods and information. A housing sub-routine could develop scenarios for optimal housing designs. A light calculator could optimise the need for and control of, natural light in built spaces. A ‘function mixer’ would propose optimal mixtures of activities according to economic, social or cultural criteria.

Maas speculates that systems such as the Regionmaker could become decision support systems in a more pro-active and critical sense. “We could add an Evaluator, or an Evolver that can suggest criticism of the input we make,” he speculates. But there will never be a single programme for everything – and Regionmaker will never be finished. “We think of it not as all-in-one Big Brother software, but as an intricate network of different software programmes operating at different spatial dimensions.”