a shift of focus in design from place making, to place connecting.

In place of an architecture concerned with discrete buildings, – or the design of stand-alone products – the new priority is relationships. As the biologist Andreas Weber points out, this is how nature works, too: The practice of ecology is the forging of relationships.

A fourth enabling condition for system change is that a new kind of infrastructure – social infrastructure – takes precedence over the concrete kind.

Social infrastructure is important because, as we change the way we govern our communities and our ecosystems, a variety of different actors and stakeholders need to work together.

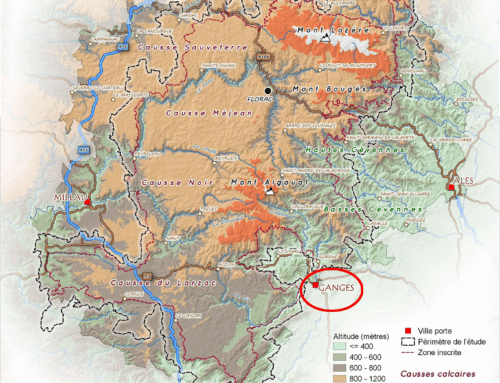

The exploration of social and cultural assets, for example, can involve a range of skills and capabilities: the geographer’s knowledge of territory; the biologist’s expertise in habitats; the ecologist’s literacy in ecosystems; the economist’s ability to measure flows and leakage of money and resources.

Institutional innovation

This convergence of expertise requires institutional support.

The scale and complexity of learning we have to do now is demanding, but it is not not unprecedented.

During the transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy, numerous regional institutions were invented to ease our transition. Many of these can be repurposed to do so again.

New sorts of enterprise are also needed: food co-ops, community kitchens, neighbourhood dining, edible gardens, and food distribution platforms.

In these new kinds of enterprise, paying attention to the process by which groups work together is just as important as deciding what needs to be done, if not more so.

The social infrastructure we need is beginning to appear in the form of new social and business models: Sharing and Peer-to-Peer; Mobility as a Service; Civic Ecology; Food and Fibersheds; Transition Towns; Bioregions; Housing as a Service; The Care Economy.

Platform Co-operatives, in particular, promise to be to effective ways to share the provision of services in which value is shared fairly among the people who make them valuable.

Technology has an important support role to play as the supporting infrastructure needed for these new social relationships to flourish.

The re-emergence of gift exchange can be made possible by electronic networks. Mobile devices, and the internet of things, make it easier for local groups to share equipment and space, or manage trust in decentralised ways; technology can help us transition from an economy of transactions, to an economy of relationships.

Technology can also help reinvent cooperative practices in rural contexts: sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting, exchanging, & swapping – in which money is but one means among many of holding or exchanging value.

A focus on the local and the social does not mean abandonment of collaboration at a national or international scale.

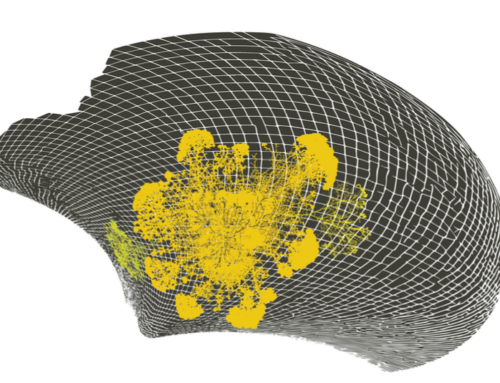

We can use technology to link projects, initiatives, and individuals in a global ecosystem.

Learning in a bioregion – and between them – can also be enhanced by the ways people in the software world find what they need on a day-to-day basis. They ask each other, in real time. The Tech For Good community, for example, keeps up to date on GitHub.

My talk today has not advocated pre-cooked solutions

It’s about building on what has already been done, in our various social and cultural histories, and on what’s being done, right now, in diverse contexts around the world.

It’s about positive change that is top-down and bottom up; long-term and short-term. It challenges us all to search for connections that are working, and those that need to be made, or repaired.

The health of a place, and of the persons who inhabit it, are one story – but it has many different versions.