May 15, 2020

In this China keynote I describe three enabling conditions for system change: a capacity for ecological thinking; a focus on social infrastructure (rather than the concrete kind); and a shift of focus from place making, to place connecting.

May 14, 2020

Social Food Forum | The Internet of Things and Earth Repair | Design Agenda for Bioregions | Peak Car | Re-wilding the Bauhaus | The City as a Living System (a selection of my texts selected for publication by Resilience magazine)

May 13, 2020

Paving over the soil, and filling our lives with media, obscured our interdependency with living systems. We must learn to think of the places where we live as ecosystems, not as machines. (This was my first keynote in Shanghai)

May 12, 2020

The word ‘transformation’ sounds uncontroversial - but does any of us has the right to transform somebody else’s life without them being part of the process? (An interview at Alison Clarke's Victor Papanek exhibition in Barcelona)

May 11, 2020

What is innovative in design today? What urgent issues is the discipline tackling? For this special feature in Domus Magazine, Valentina Croci talks with Paola Antonelli, Aric Chen and John Thackara. Paola muses on the disturbed relation between us and nature, the subject of her (then) forthcoming show at the [continue …]

May 8, 2020

Manifesto For Utopias Are Over | Healing the Metabolic Rift | Sustainability, Design and Old Growth | Tour of the New Economy | When Value Arises From Relationships, Not From Things (A selection of articles reposted by P2P Magazine)

February 29, 2020

On the island of Bornholm, in the Baltic Sea, a curious figure is handing out small packages to strangers in the high street. The young woman is dressed in orange, water-resistant clothes that are dirty, smelly and oversized. (On why art matters so much)

January 2, 2020

The prospect of an ecological civilisation is transformative In three profound ways: care for place takes priority over ever-growing production and communication; value creation is defined in terms of healthy soils, and ecological restoration; 3 an EC gives priority to social relationships, and institutional innovation.(My keynote to the China Eco-Civilization Research and Promotion Association)

December 10, 2019

Tree-consciousness | Cotton Capitalism in India | 32 Case Study Collections | Learning journeys | Water museums | Social fermentation | Shanghai’s BIOfarm | Bioregional fiber economies

November 1, 2019

Takeaways from the big Urban-Rural exhibition I curated in China: Urban and Rural are one place, not two | the same goes for Analogue and Digital | A farm is not a factory - it's a social and ecological system | my definition of 'Sustainable Fashion' | Old knowledge and new tech are not a choice - we need both.

October 28, 2019

(Press Release) Many people want to reconnect with nature and rural life - but cannot move out of the city for good. Zhangyan Harvests Festival in Shanghai, in November, is filled with practical ways to reconnect the two worlds. Located in a beautiful high-tech agricultural dome, an exhibition called Urban-Rural features a dazzling array of real-world projects.

October 3, 2019

Rewilding AI | Bioregional design | Social Food Atlas | Back to the Land Reader | Meetups and Residencies chez nous

June 8, 2019

Some of my more popular talks on video: From Biomedicine to Bioregion - The Geographies of Care | Thinking Like a Forest | Future Ways of Living | The Skills We need | Regenerative City | Social Farming

June 3, 2019

My research agenda in China: Care. Value. Place | Rewilding the Bauhaus | Social Food Forum takeaways | "Making as Connecting" - text for Atelier Luma book

May 18, 2019

Annie Proulx on Barkskins | Simone Weil on The Need for Roots | Pamela Mang on Storying of Place | Jane Memmott on Ecosystem Interactions | Arturo Escobar on Buen Vivir | Gloria E. Anzaldúa on weaving | Ann Whiston Spirn on Bacterial Urbanism | Margaret Wheatley on Emergence | Molly Scott Cato on Gaian Economics | and many more

May 15, 2019

Drawing on my work organising Doors of Perceptions and xskools in 20 countries, the following three research topics are the focus of my contribution at Tongji University in Shanghai (D&I): Care. Value. Place | Urban-Rural Reconnection | Knowledge ecologies and scale

April 20, 2019

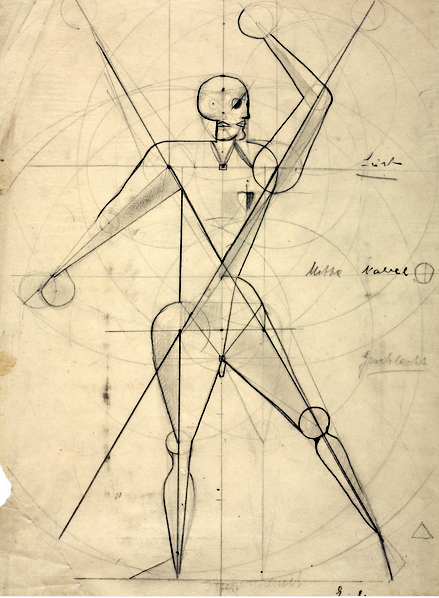

We lack situated and embodied experiences - a sense of interdependency with living systems. I therefore propose a new Bauhaus Vorkurs, or Foundation Course. The course would foster ecological literacy, and a whole-systems understanding of the world. It would unite wisdom traditions from other places and times, with the latest insights of systems thinking and complexity science.

April 13, 2019

My 6k words paper for She Ji. Keywords: Bioregion | Urban-rural reconnection | Civic ecology | Social infrastructure | Smart villages | System change | Knowledge ecologies

March 23, 2019

Social food projects re-make relationships between people, food and place | They reconnect urban and rural | As a medium of hospitality, they create solidarity and mutual understanding | They diversify income for farmers | They enhance the health and well-being of socially-isolated people | They can increase biodiversity ...

October 31, 2018

October 24, 2018

The Greek physician Hippocrates described the effects of “airs, waters, and places” on the health of individuals and communities. The industrial age distracted us from this whole-systems understanding of the world - but we are now learning again to think of cities as habitats, and as ecosystems, that co-exist on a single living planet. (Chapter for a new Cite du Design book)

August 29, 2018

Most of the component parts for ultra-light mobility ecosystems are on the table - from cargo bikes, to sharing platforms. But how to make them work together as a city-compatible system? My advice to city managers: First, visit India and marvel at the richness of bike-based commerce. Second, go to Indonesia and marvel at the range of services available on the Go-Jek platform. Next - well, read on

May 25, 2018

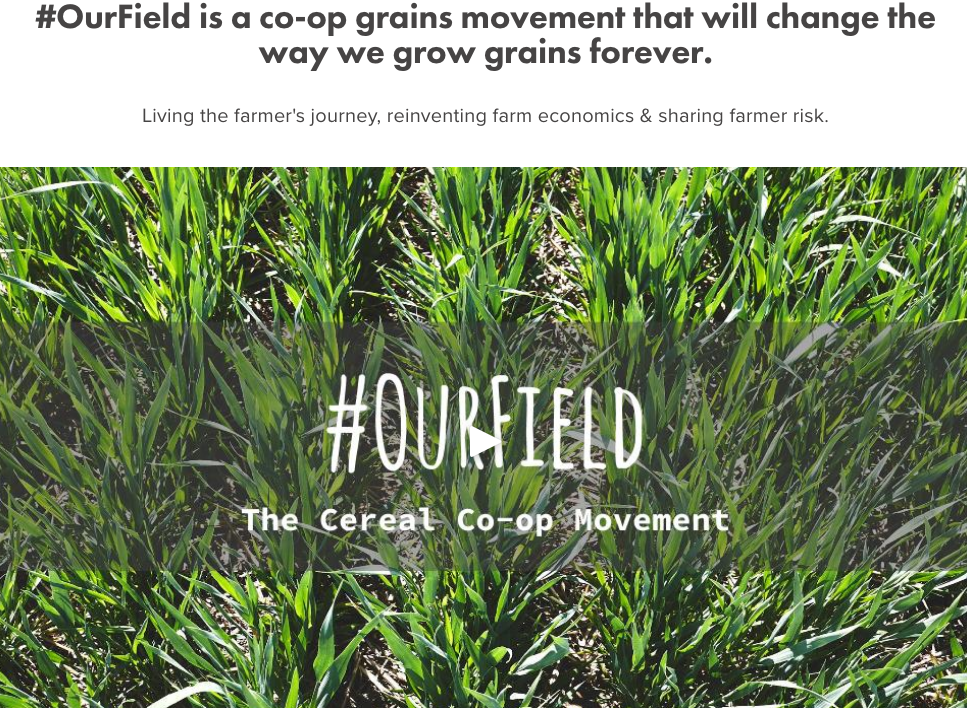

What is the a co-op grains movement, and how does it work? In this case, sixty citizens have each invested in a farmer's field for a year. Together with the farmer, they decided what to grow, how to grow it and what happens with the crop. It's a shared farming experience that supports farmers financially, and emotionally, and connects city people to what it takes to grow food.

May 18, 2018

The 6,426 chapels in Wales were once the heart of community life in remote communities. These chapels could be be part of the next economy, too - but these ways need to be designed, and with diverse collaborators. Possibilities range from CoWoLi (Coworking-Coliving), or new kinds of creative residencies, to learning hubs and new kinds of school.

May 18, 2018

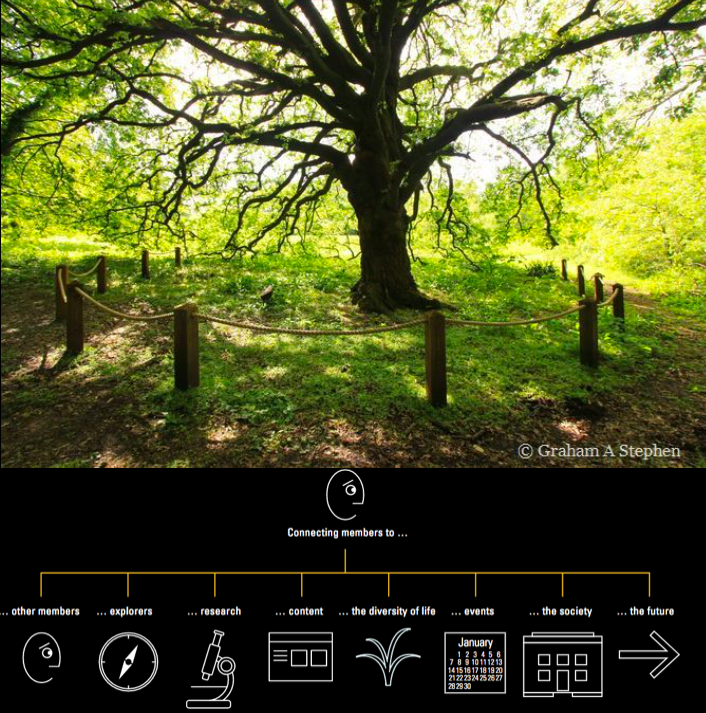

When the first botanical gardens were established 3,000 years ago, in Mesopotamia, they combined scientific enquiry with public education. Today's botanical gardens, ecomuseums, and National Parks are looking for new ways to engage citizens as active participants, not just as paying visitors. These new relationships need to be designed, enabled and supported.

May 14, 2018

The health of the soils, watersheds and biodiversity is in all our interests - so why should farmers do it all on their own? Interest is growing in ways by which citizens can play a practical role. The social, educational and health benefits of social farming can be huge - but they need to be designed....

May 8, 2018

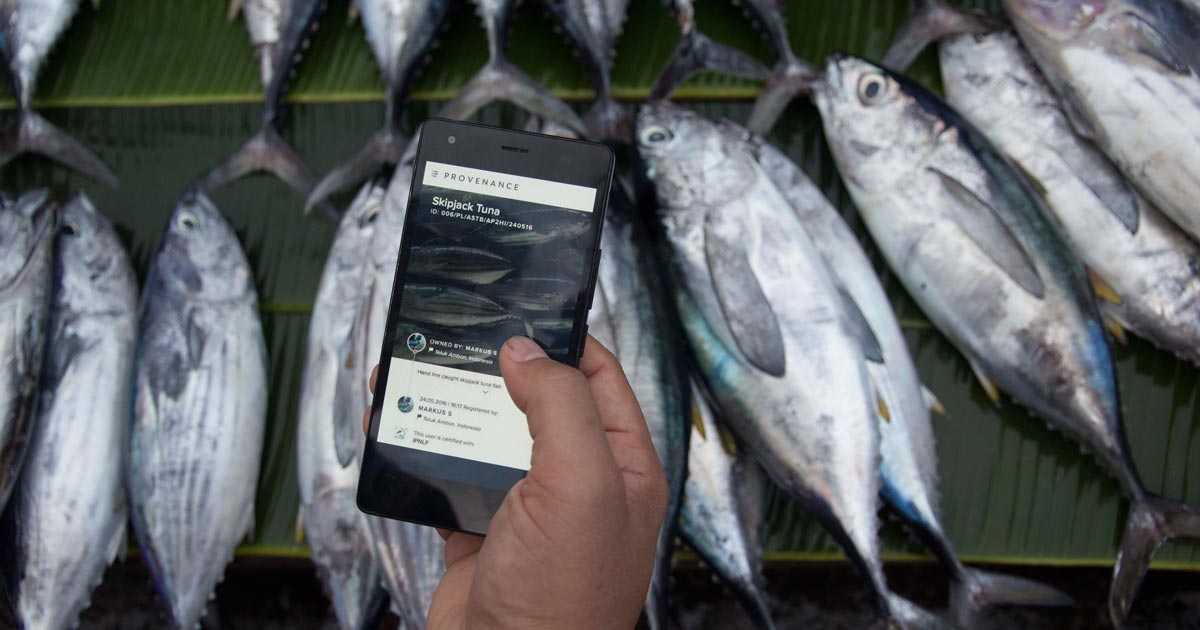

Soil health, human health, microbiomes, biodiversity, the climate - they all are connected. Digital tools can help us perceive the living world - and care for it - in new ways. Design be transformative where citizen science, and digital craft, converge.

May 7, 2018

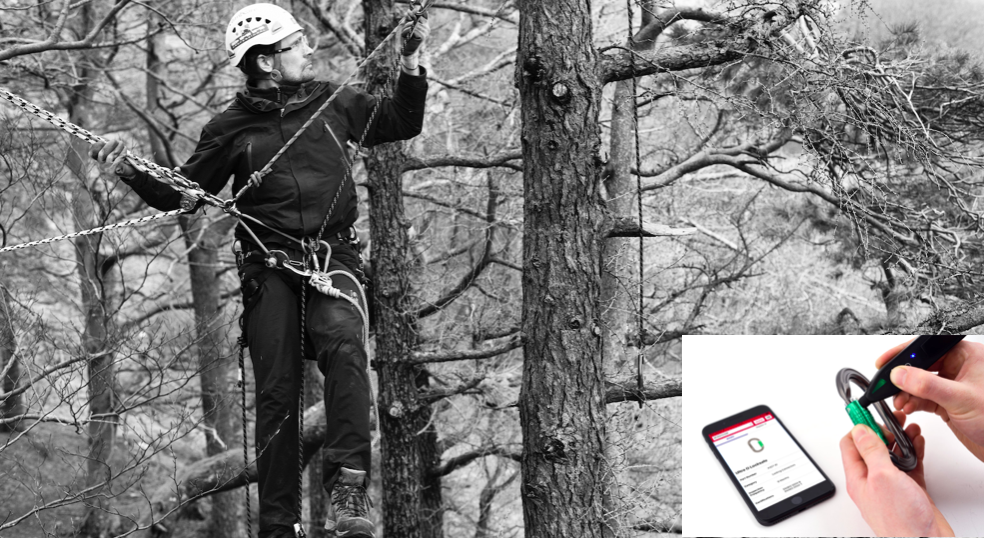

Hundreds of cities around the world are planting trees. But planting trees is just the start. A wide variety of activities and equipment - and a lot of knowledge-sharing - are involved in the management of tree popultions. Trees have to be climbed, pruned, inspected, and surveyed. All this involves equipment and services - most of which still need to be designed.

May 7, 2018

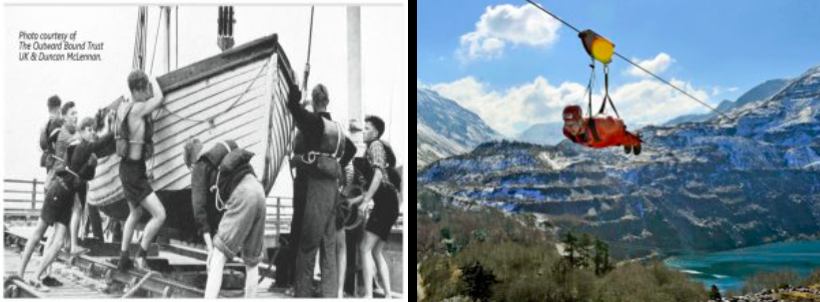

Founded in 1941, Outward Bound began as a school on the coast of Wales that trained seamen for the harsh life of working at sea. The model expanded to include outdoor, adventure-based, programs. Could Outward Bound be reinvented today as an urban-rural co-operation platform for today?

May 7, 2018

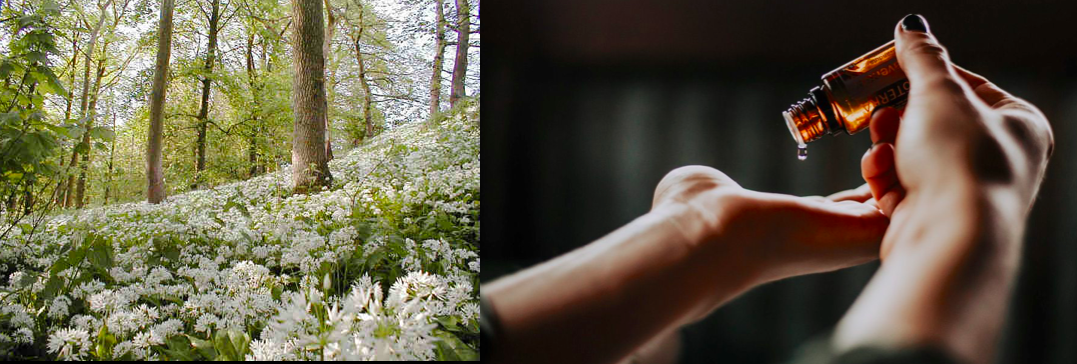

The elements of a thriving bio-economy exist in Wales - but they are disconnected. The country’s uplands, for example, are filled with grasses, and colourful wild flowers. One project scenario could be a product-service platform that links biorefining and beauty treatments.

April 28, 2018

Wellbeing is intimately linked to connection - to other people, but also to place, and the living systems that inhabit it. Relational design creates those connections (I helped design this Masters in Relational Design course for Bangor University; at this time - September 2022 - it has not been re-started since Covid).

March 19, 2018

Peak Car | Cloud Commuting | Gram Junkies | Green Tourism | Caloryville: The Two Wheeled City | From Bike Chain to Blockchain | From Autobahn to Bioregion | A Tale of Two Trains | From My Car to Scalar | Is an environmentally neutral car possible?

March 8, 2018

I’ve come to an inconvenient conclusion: production is not the purpose of life. I say inconvenient because many of us depend on industrial production to meet our daily life needs. But the perpetual search for new forms of production - whether ‘clean’, ‘green’ or ‘circular’ - is not where our future lies. (Interview with Valentina Croci of Domus Magazine)

December 17, 2017

Learning the phrase "Whatever Makes Your Dough Rise" was one of many gifts I brought back from a Fellows' retreat at the Good Work Institute in the US. What makes my dough rise is helping people reconnect with the land at the scale of the bioregion. Here are some examples of that work.

December 8, 2017

“The future will be all about cities” – say people who live in cities. Endlessly. Our xskools, in contrast, are about reconnecting with rural communities and looking, together, for ways ways to unlock value. Here is an invitation to check out our updated xskool page.

October 23, 2017

Two hundred people per second now climb onto a dockless bike somewhere in China. The bigger story? We may have reached a peak-car tipping point - a moment of system transformation - that's been slowly 'brewing' for a very long time. (This text follows my keynote at Seoul Smart Mobility International Conference).

October 21, 2017

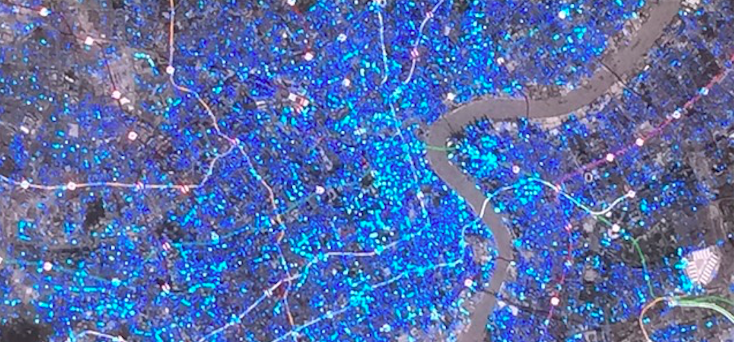

On a recent visit to @IAAC in Barcelona, I was charmed by their Smart Citizen platform. It enables citizens to monitor levels of air or noise pollution around their home or business. This innovation is impressive - but it leaves a difficult question unanswered: Under what circumstances will possession of this data contribute to the system transformation that we so urgently need?

September 18, 2017

I’ve been re-reading "the internet and everyone" by john chris jones. I’ve been astonished once again by the sensibility of an artist-writer-designer whose philosophy – indeed his whole life - first inspired me when I was a young magazine editor more than 30 years ago. Like another muse of mine, Ivan Illich, John Chris Jones was decades ahead of his time.

May 29, 2017

To effect the system change we yearn for, we need a shared purpose that diverse groups people can relate to, and support, whatever their other differences. My candidate for that connective idea is the bioregion. A bioregion re-connects us with living systems, and each other, through the places where we live. It acknowledges that we live among watersheds, foodsheds, fibersheds, and food systems – not just in cities, towns, or ‘the countryside’.

April 26, 2017

North West Wales has the potential to lead the world as a living laboratory for innovation where adventure sport, tourism, and wellness meet. To realise this potential, and turn ideas into new livelihoods and enterprise, the region's assets need to be combined and connected in new ways. But how? (I've been invited to gjve a talk).

April 8, 2017

Ecological restoration adds new kinds of value to planning and design. On this short course, I introduce you to projects, framed by their bioregion, in urban, peri-urban and rural contexts: regenerative agriculture; civic ecology; green infrastructure; river recovery; wetlands restoration; blue-green corridors; pollinator pathways; urban forests; and the use of plants to restore polluted soil

February 28, 2017

The design priority now is to foster better and richer connections between people, places and living systems - to reawaken a joyful sense of being at home in the natural world. This is where art and storytelling come in. (Interview with Sarah Dorkenwald for her book Visionen Gestalten).

February 27, 2017

The 'gig economy' and the 'precariat' may be uncomfortable novelties for people in the North - but for eighty percent of the world's population they are the old normal. As welfare and solidarity innovators, we have much to learn from different times as well as from different places. (An an edited version of my keynote to the Craft Reveals conference, Chiang Mai, 2016)

February 9, 2017

Amid the spectacular setting created by my hosts at

#PuneDesignFestival (above) my talk was miraculously summarised on a single page by the talented @ragasyThere followed a #ThackaraThrive book launch in Mumbai at the Indian [continue …]

December 5, 2016

On the occasion of the publication of #ThackaraThrive in Spanish, I did an interview for Experimenta with Dr. Eugenio Vega Pindado. Here below is the English version.

Q1: This is one of the first interviews with John Thackara in a Spanish magazine. What do you tell to our readers about [continue …]

December 5, 2016

Con motivo de la publicación en lengua castellana de su último libro, John Thackara ha concedido una entrevista a Experimenta. En ella repasa las principales ideas de su pensamiento y los motivos que le han llevado a profundizar en las relaciones entre diseño e innovación social con la mirada [continue …]

November 21, 2016

(Above: Debra Solomon examines nature’s internet at Schumacher College in England)

The Design Museum in London opens at its new home this week with, as its centrepiece, an exhibition called Fear and Love curated by Justin [continue …]

November 20, 2016

“The last thing we need to see the world with new eyes is a virtual reality headset“. On a recent visit to Milan, I was interviewed for Domus by Stefania Garassini. The Italian version is online here; the English one is here.

(Domus [continue …]

October 8, 2016

“Beware the scale trap”. In a Letter To Philanthropists Parker Mitchell, a former CEO of Engineers Without Borders in Canada, advised potential donors that “scale is important, but don’t rush it. [continue …]

September 19, 2016

Back in November, on the eve of the US book release launch for How to Thrive in the Next Economy, I sat down with Core77’s Allan Chochinov to talk about the project.

AC: When did the book project first begin? Is it something that you’ve been working on for [continue …]

Homeadmin2023-08-09T18:07:42+00:00